When an unarmed black man named Michael Brown was killed Aug. 9, 2014, by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, Cynthia Assam was just two weeks away from starting her second year at the University of St. Thomas School of Law. That October, when activists invited people from around the country to rally in Ferguson, she was taking midterms. And when a grand jury decided on Nov. 24 of the same year not to indict the police officer who shot Brown, Assam sat, numb, in tearful silence alongside two other black law students in a darkened room of the school’s legal clinic. The sounds of carefree laughter pierced through a wall, evidence that others were carrying on as usual.

“People keep going; life goes on,” said Assam, remembering the sting she felt that day. “(We) were right there – all of us law students, all of us seeing what’s going on in society. But realizing how deeply it impacts some yet doesn’t affect others at all – that’s the part I find frustrating.”

A Flossmor, Illinois, native and first-generation Cameroonian-American, Assam came to law school focused on a civil rights career. But nothing could have prepared her for studying the law in the midst of a national divide that at times has left her feeling as if her identity was split in two.

“To see the legal system (being) used to kill young black people and then their white killers aren’t held accountable, it throws the whole thing in my face,” she said. “If it’s happening right now in 2015, what am I going to do when I graduate in 2016?”

Work to be done

In the year that has followed Brown’s death, racial justice has become a national conversation nearly impossible to ignore. Preceded by the killings of Trayvon Martin in February 2012, Eric Garner in July 2014 and John Crawford III in August 2014, it was Brown’s death and the events that followed that triggered a new wave of activism.

“I think what’s happening now is a manifestation of concerns that have been bubbling up for decades,” said Nekima Levy-Pounds, a tenured professor and director of the Community Justice Project at UST School of Law. “We’ve reached a tipping point in terms of how our system of law and order operates, from the point of con- tact between people and police, all the way up to what happens when people exit the criminal justice system.”

For law students and new lawyers, particularly those who also identify as black, the post-Ferguson year has been a trying one.

“It’s been a struggle because as much as you have a sworn obligation to protect and uphold the law, you also have an obligation to protect people and ensure there’s justice for all citizens,” said Ashley Oliver ’13, who works in judicial affairs at Minneapolis Community and Technical College and has been active in the Black Lives Matter Minneapolis organization. “When laws are applied differently to different groups of people, we can see a disconnect between the intent of the law and the application of it, making it hard to simply uphold the law at face value. There are moral implications of just standing and sitting idly, and I can’t do that.”

Ashley Oliver '13 performs a spoken word piece for students from Burnsville Alternative High School during The Selma Project, an event organized by the Black Law Students Association.

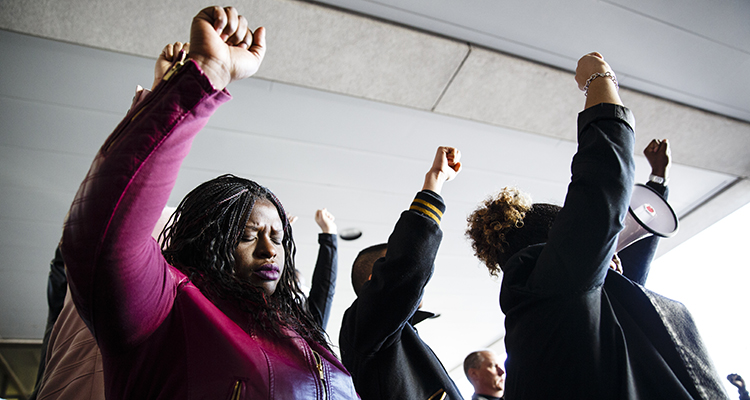

Many members of the UST School of Law community have turned their frustration into action, lending their voices and legal skills to the cause. From marching on the streets of St. Paul and Selma and through the halls of the Mall of America, to registering voters in Ferguson, working for education reform in Minneapolis, and gathering people of all ethnic, religious and gender identity backgrounds to speak on campus, students, alumni, faculty and staff have dedicated the year to calling out inequities in legal and educational systems.

“Laws are made to be challenged, especially when they are producing inequitable outcomes,” said Levy- Pounds, who faces misdemeanor charges for helping to organize a Black Lives Matter protest at the Mall of America on Dec. 20, 2014. “Often it’s our responsibility to show the larger society that certain laws are unjust and need to be changed,” she said.

As director of the Community Justice Project, Levy-Pounds leads clinical students in pro bono advocacy work that serves local communities. This year, the project’s educational team took the case of a 16-year-old boy attending Minneapolis Public Schools’ Harrison Education Center, a “level- four” school intended for students with emotional and behavioral needs. That case ultimately led Levy-Pounds and three certified student attorneys to file a federal civil rights complaint with the U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division.

“Within this school are highly concentrated populations of students of color and poor socioeconomic status,” student Aleesa Jansick said, noting that Harrison is 93 percent black, with 95 percent of students qualifying for the federal free and reduced-price lunch program. “It’s also the only level-four school in Minneapolis, which means it’s very hard to transfer out of unless a student leaves the district. Yet as our client describes, the education received there is appalling.”

The complaint Jansick filed along with two classmates and Levy-Pounds accuses Harrison of routinely violating the civil rights of its students by being overly restrictive and failing to provide adequate instruction. The law students hope that a threat of action from the Department of Justice will give district leaders a push to change how special education students, and those who are black and poor, are educated in Minneapolis.

“When you’re not allowing a 17-year-old to go to the bathroom by himself or take a book home, how can you expect him to be gainfully employed when he leaves?” Jansick said. “When you’re releasing a legal adult into society without any marketable skills, what do you expect him to do? All you’ve shown him is how to be detained and monitored, and that’s going to be a system he’s more comfortable with.”

The application of unjust laws

Jansick said education in Minneapolis is a racial issue because children of color are more likely to be diagnosed with emotional and behavioral disorders and placed in schools like Harrison than other students.

“What could be seen as sassiness in a little white girl might be perceived as questioning authority in a young African-American boy,” she said. “What’s scary about this system is how much of a child’s academic placement is left to a teacher or administrator’s discretion, without taking into consideration that individual’s innate biases.”

The situation is familiar to law student Ngeri Azuewah, a first-generation Nigerian-American who has experienced racial and community divisions throughout her life.

“The first school I went to was predominantly African, and I couldn’t understand why people who looked like me were always on the receiving end of injustice,” Azuewah said of her childhood in Prince George’s County, Maryland. “Growing up, I didn’t really learn that much about how the system ... oppresses certain people, but I could never accept at face value that these people are just meant to be in the circumstances they’re in.”

Now an advanced clinical student working with Brotherhood, Inc., a nonprofit founded by the Community Justice Project that helps create pathways out of poverty, gangs and incarceration for young African-American men, Azuewah sees the same story play out in the lives of others.

“It’s frustrating for me to look into their eyes and know that society may perceive them as something other than what I see in them,” Azuewah said of the young men with whom she works. “Some of them are business men, some of them are creative geniuses. They’re young men with the capacity to go beyond any expectations, and if they are just given the space to exist, they can excel at anything.”

As a future lawyer, Azuewah views the national debate about the killings of unarmed black men as a muddled conversation about how laws are carried out.

“You can have something in the books, but the enforcement of laws is a different thing entirely,” she said. “Even if Michael Brown had stolen cigarettes, it doesn’t mean that he should have died. Even if any of these men were committing the crimes that have been talked about, those crimes don’t warrant death. Death shouldn’t have been the first option for these men; they weren’t justified kills.”

Hope above all else

Struggling to find a balance between her identities as a law student and black woman, Azuewah connected with alumna and former UST School of Law diversity director Artika Tyner ’06, and together they traveled to Selma, Alabama, in March for the 50th anniversary of the marches that contributed to passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Azuewah said the trip was life changing. “I was really frustrated that 50 years ago people were marching to have their basic rights acknowledged, and 50 years later we’re facing some of those same issues. But it was beautiful to see everyone come together there.”

The event provided clarity and hope at a time when she needed it most.

“As a black law student, you don’t have the luxury of reading something and taking it at face value. Criminal law, constitutional law, property – I always see myself or someone I identify with negatively depicted in what I’m reading,” Azuewah said. “It’s challenging to study a precedent that was very unjust without taking into consideration how negatively that law would have impacted me.”

Assam, too, felt compelled to do something – anything – so she made her way to Ferguson, Missouri, over spring break and went door-to-door in the divided city, helping people register to vote and surveying residents about the programs and services they need.

Law students Cynthia Assam, left, and Muna Hassan talk with a student from Burnsville Alternative High School during The Selma Project.

“I went to Ferguson because I needed to find hope that things were going to get better,” Assam said.

Another law student, Sara Gangelhoff, aimed to find the same sense of hope and understanding in a smaller setting. After noticing that some of the most diverse and rewarding discussions she had with her classmates were happening in the halls after class, she set out to make those conversations accessible and relevant to the entire student body.

“We don’t always want to speak up and be the spokesperson in every single class for every single issue, but it’s important as a law student to assume that everyone is looking at a case or legal issue from their own perspective,” said Gangelhoff, president of UST School of Law’s Jewish Law Students Association, vice president of its Louis D. Brandeis Law Student Chapter and social chair of the school’s Latino Law Students Association. “Once we start treating these viewpoints not as outliers, but as essential to the conversation, we can see that diversity is important, and be better able to understand our diverse clientele as lawyers.”

To start discussions, Gangelhoff worked with nine student-led affinity groups to organize a two-week-long event series, “Perspectives,” which brought in speakers representing a wide array of racial, religious, sexual- orientation and vocational backgrounds to speak on the shared topic of World War II. In each discussion, the legal lessons of the WWII era were tied to relevant issues faced today.

“Part of overcoming (sensitive) issues is not to make these conversations easier, but just to have them in the first place,” Gangelhoff said. “Once you learn the language, you stop tip- toeing around what you can and cannot say, and that makes us better students, and it will make us better lawyers.”

Ashley Oliver, just two years out of law school herself, sees young lawyers as having the most potential to turn the national fight for racial justice on its head.

“Lawyers have been trusted to carry this torch of knowledge and serve as arbitrators of justice,” Oliver said. “There is a change happening in the legal landscape right now that each of us needs to be present in.”

Levy-Pounds is a stark example of that presence. Within weeks of being charged for her participation in the Mall of America protest, she was named an Attorney of the Year by Minnesota Lawyer, a Minneapolis/ St. Paul Business Journal 40 Under 40 honoree, an NAACP History Maker, and a Saint Paul Foundation Facing Race Ambassador Award winner.

“I see my work with Black Lives Matter as an extension of my work here, to actually go and engage the people and see what their needs are. It’s a natural part of my work and it’s also a natural part of my scholarship and my writing,” Levy-Pounds said. “Many people expect once you’re a law professor, for you to fit into a certain box; I don’t fit into anyone’s box. It’s more about allowing the pursuit of my calling, taking the risk, going against the status quo, being relentless in the pursuit of justice, and trying to awaken the level of consciousness that exists in our society. That’s the essence of why I do what I do.”

As the newly elected president of the Minneapolis branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Levy- Pounds isn’t slowing down any time soon. There’s still a lot of work to be done, she said, in addressing racial and social justice issues.

“Laws have been used to oppress the poor, the vulnerable and people of color since the very beginning, starting with slavery to the Black Codes all the way to Jim Crow laws and currently to mass incarceration and the war on drugs,” she said.

But by the end of a semester in the Community Justice Project, her students feel empowered.

“Some have gone on to work in civil rights departments and human rights departments, or they’ve become public defenders or prosecutors,” Levy-Pounds said. “They’re going into those positions with a heightened level of consciousness and an awareness of racial and social justice issues. That will help them in their decision-making and having empathy toward vulnerable populations. It takes head and heart.”

Read more from St. Thomas Lawyer.