Seated across the table in a booth in Scooter’s in the basement of Murray-Herrick Campus Center, 23-year-old junior Lisa DeLance looks like a typical St. Thomas coed.

Her long blond hair shiny, blue eyes bright, wearing a pink cable-knit sweater, it is hard to imagine DeLance in a chemical weapons suit, hunkered down in a foxhole as Iraqi SCUD missiles roar overhead.

A criminal justice major who works full time in Public Safety at St. Thomas and goes to classes half time, DeLance joined the Army Reserve in 1999. She viewed it as an opportunity to test herself and signed up for the reserve’s “six-by-two” program, which amounts to drilling one weekend a month and two weeks in the summer over six years.

“I wanted to see if I could be a soldier, but only part time. When I joined, war didn’t seem likely,” said DeLance, when she was briefly home on leave in December.

She was on “inactive status” on Feb. 7, 2003, when her unit was deployed in Kuwait and then Iraq. DeLance is a chemical operations specialist – the newest job in the U.S. military. Essentially, a COS is responsible for cleaning up soldiers and their equipment hit in a chemical attack, and getting them back in the fight as quickly as possible.

“The modern COS has yet to have to actually do their job, thank God,” DeLance said. “But we train like crazy for it just in case.” Picture a cross between a MASH unit and a full-service car wash. “Our goal is to set it up so that it is safe, easy and stress free. We realize that our job is very important.” Back in the United States, DeLance and her fellow COS unit members also are trained to deal with any kind of chemical or radiological attack on U.S. soil.

DeLance: ‘If you’re slow, you’re dead’

DeLance spent her first month in Kuwait at Camp Coyote, attached to the 1st Marine Expeditionary Force about 30 miles south of Iraq. Her unit trained for a chemical attack on the Marines, which at the time seemed inevitable given that Camp Coyote was well within range of Iraqi SCUD missiles carrying chemical weapons. But it soon became apparent they were geared up for an assault that would never come.

That didn’t mean the Iraqis weren’t firing at coalition forces in Kuwait. The Iraqi military was vainly launching SCUDs without guidance chips into DeLance’s area at random. U.S. forces could detect the moment a SCUD was launched, sometimes picking them off in mid-flight with Patriot missile batteries or scrambling a fighter jet to shoot them down.

Nonetheless, each time a missile would launch, DeLance and her fellow soldiers had to put on their protective masks and suits and run for the nearest foxhole. During the war, DeLance said the SCUD alerts could be five to 10 times a day and she’d sit in the bunker for anywhere between five minutes to an hour before the all clear was sounded.

“The suit adds about 20 degrees to the temperature. And in Iraq it’s usually hot (120 degrees is not uncommon), so the suit gets very hot very fast, like a sauna. The mask has a tube that’s hooked up to your canteen and you just keep drinking water. It can be complicated. You train for it, but when it’s for real, you almost stop breathing and it’s scary,” DeLance said.

Soldiers have eight seconds to clear and seal their masks and 15 seconds to don them and eight minutes to put on the suit and boots. “In basic training, the drill sergeants have stop watches. And if you take more than eight seconds to clear your mask, they just look at you with no expression on their faces and say, ‘You’re dead.’ Over there, if you’re slow, you’re dead.”

When it became apparent that the Iraqis were not using chemical weapons, her unit decontaminated equipment, like bombs, so they could be shipped back to the states. She liked the duty because “I made a lot of friends. It was fun meeting so many different people with different points of view.”

By the end of August, DeLance’s company was packed and ready to head stateside. But then her unit was assigned to a base in An Nazaria in southern Iraq. “We were shocked,” DeLance said. “We had been planning on going home by the end of September.

“When we heard we were going to An Nazaria, we breathed a sigh of relief because we thought of it as a safer area. An Nazaria saw some of the worst fighting at the outset of the war. Jessica Lynch was captured there and there were lots of casualties. But once the fighting subsided there was very little insurgent activity. It was Shiite-controlled and they were generally friendlier to the U.S. military.” However, it was in An Nazaria that 16 Italian soldiers died from an insurgent bombing.

An Nazaria was bare bones. “In Kuwait, you had fast food in trailers,” DeLance said. “There was a Subway trailer, a Pizza Hut trailer, you name it. But in An Nazaria, there was nothing like that. About a week after we got there the Army Signal Corps set up an Internet Café with four computers for checking e-mails – usually about a two-hour wait. No phones were available.

“It was the only way to communicate with home and feel like you really still belonged back there. My dad (Larry DeLance) served in Vietnam, so being able to reassure him that I was in a safe area really helped.”

Swenson: ‘MP stands for multipurpose’

Lisa has never met Joel Swenson, a 24-year-old senior in criminal justice four credits away from graduation. Swenson, now a corporal, is a member of the Marine Reserves military police stationed at Fort Snelling. He was back in St. Paul last fall and returns to Iraq this spring.

Swenson also joined the reserves in 1999, eager for the physical challenges. He is a field MP. Rather than rounding up drunken Marines who overstay their leaves, field MPs train for battlefield situations. They handle POWs; work in battlefield circulation and control, which amounts to making sure Marines are where they need to be when they need to be there; and scout and keep open routes for military convoys.

“We always say,” Swenson said, “‘MP stands for multipurpose.’”

After training for six days at North Carolina’s Camp Lejune when he was activated Jan. 29, 2003, Swenson and fellow reservists flew civilian aircraft to Camp Matilda in Kuwait, home to 5,000 Marines with the 1st Marine Division. “Everything’s a lot more intense than it was in the reserves,” Swenson said.

All 80 men in his company were housed in what looked like circus tents, “packed in there shoulder to shoulder on the wood floor like a bunch of sardines,” he said.

At the first morning briefing, Swenson’s battalion commander told the assembled troops, “You take the KU out of Kuwait and you’ve just got wait. But we’re not waiting any longer.” The invasion of Iraq was about to begin.

Swenson’s unit moved from Matilda to an “assembly area” several miles south of the Iraqi border. Attached to an assault amphibious battalion, the MPs rode in Humvees equipped with .50 caliber machine guns and grenade launchers, with their packs strapped to the outside. “I remember some of the guys having trouble getting their packs on they were so heavy – they averaged 100 pounds,” he recalled.

Swenson carried a 240 Gulf machine gun that can fire 600 to 700 rounds a minute, the heaviest of the hand-held machine guns. In a battle situation, his job was to lay down heavy suppressive fire. “It’s easy to take for granted how much power you’re holding in your hands. But for me it always felt like a big responsibility,” Swenson said.

His job was to race ahead of the convoy, like a motorcycle cop escorting a motorcade, make sure the way was still secure, and then drop back and cover the convoy’s flank.

“Our orders were to move in on anybody we saw, identify them, sight in on them, make sure they weren’t an immediate threat to the convoy, and then keep moving,” he said. “The emphasis was on speed and safety.”

But one day, while traveling cross-country, Swenson’s team found itself smack dab in the middle of an Iraqi minefield. “Nothing blew,” he recalled. “Once we realized we were in it, we had to slowly back out the same way we came in by following our own tracks.”

The convoy covered 300 miles in 21 days, ending up on the outskirts of Baghdad, where Swenson and his fellow MPs were assigned to secure a bridge critical to the coalition troops’ access to Baghdad. Just one problem: the bridge was rigged to explode. Navy Seabees had constructed a span over an already demolished section of the bridge. It was Swenson’s job to keep military vehicles off the bridge until the explosives could safely be removed.

But before that work could be done, a battalion of tanks came roaring up in “attack posture,” and when Swenson approached the lead tank, the battalion commander aboard barked out, “Listen up, stud! We are in attack mode! So step aside!”

“I had to assume he knew something about that bridge I didn’t because he was putting his Marines in jeopardy, not to mention ours,” Swenson said. He held his breath as the column of tanks rumbled safely across.

“In war, nothing’s perfect. You’re constantly improvising and reacting to the situation,” Swenson said.

Dibaki: ‘There is no certainty around here’

U.S. Army Sgt. Collins Dibaki is a junior studying computer science and finance and would like to run his own business some day. But for now, he is on duty in Iraq and was interviewed by e-mail.

He measures the future in much smaller increments than he used to. Getting through each day in Iraq is about as far ahead as Dibaki feels he can plan. He draws from his training for any sense of security he can muster. And he feels he’s ready for whatever may come.

“Basic combat training gave me a feel of what this was going to be like,” he said. “I learned to deal with things like sleep deprivation, not having all the comforts like a warm shower or seeing loved ones. The training plus your individual survival instincts keep you alive in this part of the world. Discipline is the highest motivator. Knowing what, where and when you are supposed to be at any given time makes life easier as a soldier.”

He can’t discuss the specifics of his mission or where he is, but Dibaki e-mailed from Iraq that the most boring duty is also the potentially most dangerous – “guard duty because it is just monotonous. You see the same thing over and over for hours. And boredom is not a luxury any soldier serving in Iraq can afford. At nights or in the early morning hours when there is low visibility, the enemy believes they can successfully conceal themselves under the cover of darkness.

“I know or expect the worst to happen at any given time or place,” Dibaki wrote, “There is no certainty around here.”

Warner: ‘Volunteers can make a difference’

Nate Warner, 24, is home after eight months in Iraq and “getting used to snow again.” He is majoring in international business and will graduate in May 2004.

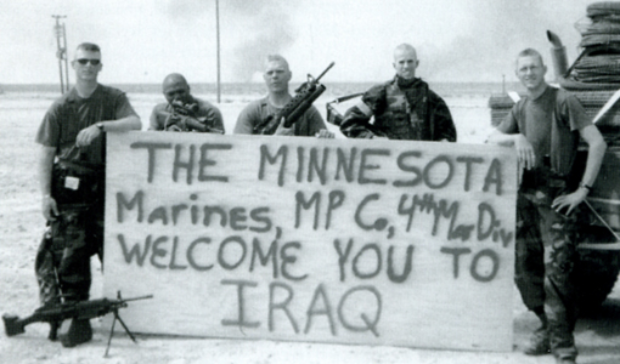

After being on the front lines, crossing the Iraq border the first day of the U.S. attack and moving on to Baghdad, Warner has finished his reserves duty, although “I can be called back if there is absolute need.” As a Marine corporal with the 4th MP company, he said he would do it again. “It is an adrenalin rush, and there is the satisfaction of doing your part. Usually people are not in a position to make a difference in the world, but volunteers can make a difference,” he said. “I get satisfaction from serving my country.”

And Warner clears up a few misconceptions. He found that constant danger can make one “rather desensitized to danger. Once we were eating lunch and just ignored a guy who jumped out of a building and began shooting at us. We just kept eating and another unit took care of him.

“Also, the reserves serve as well or better than the active duty elements because they are well-trained, older (average age 25), have skills from their everyday jobs, and usually are more educated.

“Personally, I also found that a well-rounded liberal arts education made me look at everything from a different perspective and made me better able to relate and deal with the populace of Iraq.

“And no one joins the reserves for the money, $225 a month in my case.”

And what do Marines do on a day off? “We tried to get to Army bases,” Warner laughed, “since the Army has more funding and so has better food. We say it’s like Disneyland.

“It is good to be home, safe and sound,” Warner said, “but I would feel horrible if something happened to my unit which goes back to Iraq in February and I was not there to help. I miss them but I have to move on.”

Theology, the law and liberal arts

While their experiences in Iraq varied, the students said their education helped them to come to terms with the war.

Dibaki credits his philosophy and theology courses with helping keep things in perspective under the pressures of combat. “Being able to accept that this is my fate and that no matter how much I do not like being out here, I just have to make the best of the opportunity that has been given to me,” he said.

Swenson’s experiences in Iraq have helped him bring greater focus to his education. “I hadn’t really gotten too excited about school and looked into the Marines for the physical challenge. But I found my niche taking law classes during my training in the Marines.” He plans to go to law school.

DeLance credits her education with enabling her to maintain perspective in the chaos and brutality of war. “The liberal arts education definitely left me with a different attitude toward the people of Iraq, a different view of what it’s OK to do while you’re serving over there and an appreciation of individual human rights. It helped me to strike a balance between keeping myself safe and respecting the rights of the Iraqi people, who, after all, we’re supposed to be liberating. They are just trying to live their lives in all that chaos,” DeLance said.

“The girl in the next bunk had a less nuanced view of Iraqis. To her, an Iraqi was an Iraqi. But then, that sort of a simplistic view can save your life. And that’s why the Army teaches it to you.

“This entire experience has been a learning one that I couldn’t have gotten any other way. I’ve learned so much about people, my fellow soldiers as well as Iraqis and Kuwaitis. You take the good with the bad. I have no regrets.”

Jim Leinfelder is a free-lance journalist and television producer for “NBC News” and the “Dr. Phil Show” on CBS. Leinfelder was in the St. Thomas class of 1981 but still owes two credits, “which I will finish this spring semester.” He lives in St. Paul.