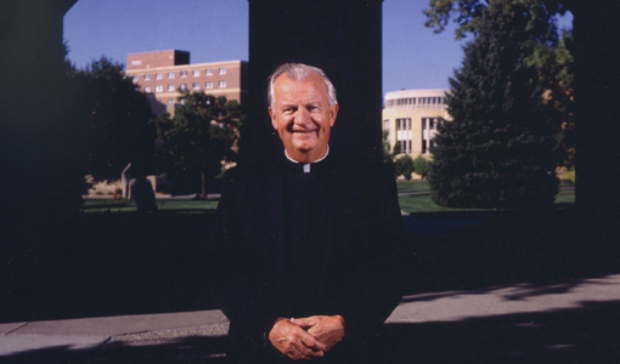

Looking back on a 25-year run as president of the University of St. Thomas, Monsignor Terrence J. Murphy summed it up neatly in 1991: "We've been on an interesting journey."

Murphy, who led St. Thomas evolution from a small liberal arts college to a comprehensive university, died Feb. 25, 2004. He was 83 and had served St. Thomas for 50 years. Murphy was president from 1966 to 1991, and at the time of his death was the university's chancellor.

The journey that Murphy mentioned in his reflections was that of the university, but it also was his own. It was a journey guided by the words of St. Thomas founder, Archbishop John Ireland.

"John Ireland dreamed of a university that would produce educated men and women for the clergy, for professions and for business," Murphy told the St. Thomas Presidents Council in 1990. "He wanted to train both the mind and the heart. He wanted the immigrant Catholic population to become part of the mainstream of American society. He had a great and abiding concern for the welfare of the community.

"The challenge of this courageous, far-sighted man rings down through the years," Murphy said, and then recited a quote from Ireland: "Into the arena, priest and layman, seek out social evils, and lead in movements that tend to rectify them."

"That challenge so struck me when I was still a seminarian that I memorized it and it has been with me all these years. It has been and is our constant guide."

When Murphy was a seminarian, he could not have known that someday he would lead the university that Ireland founded. But there is no doubt that Murphy took Irelands challenge and guidance to heart.

"I never sat down and said, 'I have this big vision for the college, " Murphy once told a St. Paul Pioneer Press reporter. "I wanted to hold fast to fundamentals – the colleges liberal-arts character and its Catholic character. I was concerned with being open to the people, the students. I had ideas, not visions. And the college evolved."

That 25-year evolution saw St. Thomas:

- Become coeducational and a university.

- Expand its graduate programs from one to 13, including its first two doctorates.

- Grow from 2,167 students to 9,120 students.

- Increase its faculty and staff from 257 to 1,324.

- Increase its annual budget from $3.5 million to $84.4 million.

- Open three new campuses outside of St. Paul.

"The church and society lost one great man in the death of Monsignor Murphy," said Archbishop Harry Flynn, chair of the university's board. "He was a real servant."

When appointed president of St. Thomas, "Murphy rose to new and great heights," Flynn said. "It was under his tenure that St. Thomas reached the prestigious stature that it now enjoys under the outstanding leadership of his successor, Father Dennis Dease.

"Monsignor Murphy was an educational visionary and always grounded by the Catholic identity which so marks, and should mark, every Catholic university," Flynn said.

"I am saddened by the loss of this good-natured priest and friend," said Dease. "Mild-mannered and eminently likable, Terrence Murphy distinguished himself as a wise and extraordinarily successful educator, a remarkable entrepreneur and a true visionary.

"This university community owes him an immense debt of gratitude. It is one that shall not soon be forgotten."

Another friend, David Laird Jr., president of the Minnesota Private College Council, said Murphy was an exceptional leader during difficult challenges for higher education.

"While focusing on major developments at St. Thomas, he was a spirited leader among the presidents of the Private College Council. His commitment to assisting students from less-advantaged backgrounds to have real access to higher education was unwavering.

"Monsignor Murphys dignity, humility, values of service, and unselfishness were the hallmarks of his leadership. In a generation of outstanding and gifted leaders in our society, he should be remembered as one of those who set the pace."

When he retired, Murphy had the longest tenure of any president in Minnesota. Named to a list of the nations 100 most-effective college presidents (and one of the top 10 Catholic college presidents) he once cited a study that examined the attributes of 19 highly successful schools.

"They all had long-range plans É but they didnt pay much attention to them," he said. "A plan is not what made the difference at St. Thomas.

"The difference was being entrepreneurial and the ability to sit back and see the needs, and then have the willingness to meet the needs."

The middle of seven children, Murphy was born Dec. 21, 1920, in Watkins. He later lived in Green Isle, and when he was in the sixth grade the Murphy family moved to St. Paul.

He attended Nazareth Hall and the St. Paul Seminary, where he received his bachelors degree in philosophy. He was ordained to the priesthood in 1946.

Among his classmates were James Shannon and John Roach, both of whom died last year. All three were known widely for their interest in social justice and dedication to liberal arts and values-based education. Roach served as archbishop of St. Paul and Minneapolis from 1975 to 1995. Shannon was president of St. Thomas from 1956 to 1966.

Following his ordination, Murphy did parish work at the Cathedral of St. Paul and in Belle Plaine. He became an Air Force chaplain in 1949 and was on active duty during the Korean War, serving in Florida, England and Tennessee. He left active duty in 1954 and for the next 19 years was staff chaplain for the Air Force Reserve. In 1975, he joined the Minnesota Air National Guard as its chief of chaplains. When Gov. Rudy Perpich appointed Murphy a brigadier general in 1988, he was the states first chaplain to reach that rank.

Murphy came to St. Thomas in 1954 on the recommendation of Shannon, who later said, "I want to have it carved on my tombstone that I helped bring Terry Murphy to St. Thomas." While teaching religion and living with students in Ireland Hall, Murphy began graduate studies in political science. He received a masters from the University of Minnesota in 1956 and a doctorate from Georgetown University in 1959.

After returning to St. Thomas, Murphy joined the political science faculty and became active in civil liberties. He led a successful effort to enact Minnesotas first fair housing bill in 1961. That year he became dean of students and in 1962 Shannon named him to the new position of executive vice president.

Four years later, in 1966, Murphy was named president.

Murphy once told the story of two meetings he had with Archbishop Leo Binz, who was encouraging a reluctant Murphy to become president. "I kept insisting that he had the wrong person . . . he terminated the first interview by hitting the desk with his fist and saying, 'Its after dinner. I am tired of talking to you. Go home, call me in the morning, and tell me you have accepted. "

At the second meeting, a week or so later, Binz told Murphy: "You were ordained a priest to offer sacrifice, the sacrifice of the Mass, but the first sacrifice a priest must offer is that of himself. You are now called upon by your bishop to make a sacrifice in the interest of the church. Are you willing to do that?"

"When the offer was couched in those terms, there was only one answer I could give," Murphy recalled.

"When I spoke to my first board of trustees meeting in 1966, I said St. Thomas was doing well and I didnt anticipate any great changes," he recalled in an interview two years ago. "But then we started building, and our big growth started coming after the Vietnam War was over. I didnt know it, but I must have been an entrepreneur at heart."

Murphy spent the early years of his presidency addressing St. Thomas finances and laying the groundwork for changes that would begin in the mid-1970s. During a 1973 brainstorming walk with Dr. Charles Keffer, then dean and vice president for academic affairs, they pondered how St. Thomas could best meet the regions educational needs.

The next year St. Thomas launched a master of business administration program with 76 students. That program experienced explosive growth and served as a model for the host of professional graduate programs that followed.

In 1975, St. Thomas established an evening and weekend division for nontraditional students, and two years later became coeducational at the undergraduate level.

Murphy also led the college through two capital campaigns, Priorities for the 80s and Century II, which helped underwrite St. Thomas expansion in St. Paul and elsewhere. He accepted the gift of the rural Owatonna home and estate of his friend, Daniel C. Gainey, which led to the 1982 opening of the Gainey Conference Center. Two years later, in 1984, he accepted a gift from the Peavey Co. that became St. Thomas Chaska Education Center and an incubator for small businesses.

Four years later, in 1966, Murphy was named president.

The success of those undertakings led him to test the waters in downtown Minneapolis, and in 1987 St. Thomas began offering classes at a remodeled department store. That led to the opening of a permanent campus in 1992. The original campus building at 10th Street and LaSalle Avenue was named Terrence Murphy Hall in May 2000.

With the new campuses and a dozen new graduate programs, Murphy decided in 1990 to restructure St. Thomas into a collection of graduate schools and an undergraduate division, and to change the name from "college" to what it had become under his watch – a university.

Murphy has been credited with hiring an entrepreneurial staff and faculty, and with giving them rein to succeed or fail. He developed many friends in the regions corporate and political communities and assembled a board of trustees that proved to be extraordinarily generous and involved.

"It was fascinating to participate in this process," Murphy wrote in his 2001 book, A Catholic University: Vision and Opportunities. "It started with nothing more than a desire to be of service."

Murphy drafted the book during his years as chancellor, when he had time to step back from the fray and write about the nature of a Catholic university and its role in society. He emphasized the themes of teaching religious and ethical values, ecumenism and openness to those of all faiths and cultures; service; recognizing and meeting community needs; and an entrepreneurial spirit.

"A Catholic university that holds to its principles and has a Catholicism that is apostolic reaches out and relates to the community of all faiths," he wrote.

A clear example of that came in 1985 with the creation of the Center for Jewish-Christian Learning, which has become a joint program of St. Thomas and St. Johns University.

"Through the center, and in the spirit of the Second Vatican Council, we have the opportunity to promote harmony and respect between the Jewish and Christian worlds," Murphy said in announcing the new center.

Among the honors Murphy received were the National Jewish Humanitarian Award in 1985 and the Brotherhood/Sisterhood Award of the National Conference of Christians and Jews in 1989. In 1995, he received the Edgar M. Carlson Award for distinguished service from the Minnesota Private College Council. The following year, he received the Elizabeth Ann Seton Award, the National Catholic Education Associations highest honor.

He was named a 'Great Living St. Paulite' in 1991; at that time, the award had been bestowed only 18 times in the 123-year history of the St. Paul Area Chamber of Commerce. Gov. Arne Carlson declared May 2, 1991, to be Monsignor Terrence J. Murphy Day in Minnesota. Minneapolis Mayor Sharon Sayles Belton declared May 11, 2000, as Terrence Murphy Day in Minneapolis.

Murphy received honorary doctorates from St. John's University, St. Mary's College and the College of St. Catherine. The St. Thomas Alumni Association named him an honorary alumnus in 1991, the same year St. Thomas gave him an honorary doctor of laws degree.

"For all of your success," the honorary degree citation noted, "you often have said that you would like most to be remembered as a good priest."

It was as a priest and friend that Murphy spoke at a January 1978 prayer service in the rotunda of the Minnesota Capitol for Sen. Hubert H. Humphrey.

"His day of death is a birthday into a new and better life. And so we dare to make this day a day of celebration," Murphy said. "We celebrate today not death, but life and the triumph of the human spirit as shown in the life and death of this remarkable man."

Murphy's words were meant to honor a great Minnesotan and comfort his family, of course. Today, they do a remarkable job of describing the good priest who spoke them.