HONESDALE, Penn. - Dusk is approaching, and from the farmhouse you can see lights on in the second floor of an old chicken coop and horse stable. John Kascht hunches over a drawing table and stares at a blank sheet of paper, surrounded by photos of his subject matter. He deftly swipes a pencil across the paper and looks up to cock his head sideways and stroke his goatee before taking another swipe. He repeats the motion over and over, hardly touching the paper but, swipe by swipe, brings life to the face.

The sketch becomes more noticeable with each layer of graphite, and the 44th president of the United States takes shape - the angular face with its wide cheekbones,deep chin, big-toothed grin, heavy eyebrows and extended ears. Barack Obama is smiling at you, and you smile back at him.

What started out as a simple pencil sketch has evolved into a caricature - one of dozens that Kascht has drawn of Obama and one of thousands that have filled a 30-year career in which he has become one of the best-known caricature artists in the United States. More smiles are forthcoming. Kascht wanders over to an oversized architect’s portfolio stuffed with movie stars, singers and business leaders, and removes pieces of heavy drawing paper. His visitors can only gasp in admiration as he holds up the caricatures, resplendent in their watercolor glory, one by one.

David Letterman. Alan Greenspan. Woody Allen. Whoopi Goldberg. Pete Seeger. Toni Morrison. Mike Jagger. Katharine Hepburn. Bill Murray. Rudy Guiliani. Conan O’Brien.

The list goes on and on - all subjects of Kascht’s fertile imagination and brilliant drawingand each lionized on magazine covers, in National Portrait Gallery exhibitions and films, on billboards, Broadway marquees and "more than a few cocktail napkins," as Kascht self-deprecatingly boasts in his website biography. Perhaps his most ambitious project, an interactive "book" available as an iPad app, went on sale this fall.

Not bad for a kid who says he liked "to slip into people’s skins," once compiling sketches into a "Nun of the Month" pinup calendar that he shared with friends before a junior high school teacher (a lay person, by the way) seized it.

Not bad for a precocious 14-year-old who marched into the Waukesha (Wisconsin) Freeman with his drawings and editorial cartoons and told the receptionist, "I want to see the editor." The editor, perhaps amused by the youth’s moxie, agreed to look at his work - and hired him on the spot.

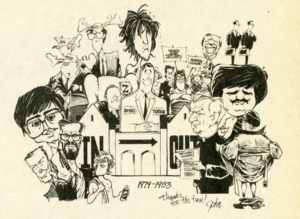

And not bad for a high school graduate who followed his best friend - his older sister - to St. Thomas in 1979, and as a freshman drew cartoons for The Aquin and black-and-white portraits of presidential candidates for Page 1A of the old Minneapolis Star.

"My earliest memories are of drawing pictures," he said. "I was born with an impulse to create, and I suppose that is unusual. If I had a few free hours in a day, I’d be in my room with a piece of paper, a bunch of cardboard and Scotch tape, and I’d be drawingand making something."

"My earliest memories are of drawing pictures," he said. "I was born with an impulse to create, and I suppose that is unusual. If I had a few free hours in a day, I’d be in my room with a piece of paper, a bunch of cardboard and Scotch tape, and I’d be drawingand making something."

Kascht also was politically literate. He followed Watergate, a gold mine for cartoonists and satirists, read MAD magazine and admired the work of Garry Trudeau and a new comic strip called "Doonesbury." One Kascht cartoon showed Richard Nixon dressed as Santa Claus and holding bugging equipment: "He sees you when you’re sleeping, he knows when you’re awake ..."

At the Waukesha Freeman, where he earned $25 per cartoon, the editor encouragedhim to focus on local issues. Readers paid attention and let him know what they thought. A woman who had been his babysitter called him once to criticize a cartoonand how "I had read this guy’s character wrong. She was very unhappy with my cartoon."

Criticism never got under his skin nor did praise inflate his ego. He just learned from them.

"I don’t remember it as being heady," he said, even when Gov. Lee Dreyfus called for acopy of a caricature. "I was always unsure enough of myself that that kind of thingdidn’t go to my head. ... I did it because it was creative, and for the love of it."

His sister, Mary Beth, enrolled in the first class with female freshmen at St. Thomas in 1977 and Kascht followed her two years later. He called his St. Thomas years "an extraordinary learning experience." He spent his junior year in London and was a resident adviser in Ireland Hall as a senior. He considered a major in theology before settling on art at St. Catherine and coming under the tutelage of Celine Charpentier, "the best teacher I ever had."

Kascht’s Aquin cartoons skewered the usual subjects, and he occasionally touched araw nerve. He recalled one cafeteria food cartoon in which a student exclaimed, "And Ithought the food was raunchy last year. This stuff is garbage." In the cartoon, the Food Service director responded, "Cost-efficient garbage," but in real life he didn’t laugh.

"He challenged me on it," Kascht said. "He wondered what the point of it was. He was good-natured about it, and I remember not having much of an answer for him. That’s why to this day, when I look at that cartoon I think it was a cheap shot because he called to my attention something I came to learn later - that just because somethingwas funny didn’t mean it was correct."

The newly graduated Kascht, armed with a hefty portfolio that included 300 tear sheets from three summer internships as a Milwaukee Journal newsroom artist, headed for Denver, where an older brother lived. The Rocky Mountain News did not have an opening for an artist or cartoonist but the editor was so impressed with Kascht’s work that he was hired anyway.

He worked as a self-described "jack of all trades" artist. This was before illustrationsoftware, so he did most of his work - illustrations, portraits, maps and charts - by hand. He learned the importance of accuracy and thrived on daily deadlines. He stayed three years before moving in 1986 to the art department at the Washington Times.

Friends asked him if he really wanted to work for the conservative Times, owned by the Sun Myung Moon of the Unification Church, but Kascht was enamored by the newspaper’s creative page layouts and dramatic use of color.

He worked as a full-time artist for three years and then as a part-time page designeruntil 2000, an arrangement that allowed him to embark on his freelance career as a caricaturist. He married the first person he met at the paper, graphic designer DoloresMotichka, and they bought a 10-acre farm in extreme northwestern Pennsylvania in 2002. Dolores also is a freelancer, with the Highlights for Children magazine among herclients, and tends to their farm’s 500,000 honeybees.

As a freelancer in Washington, Kascht weighed whether to focus on political cartoonsor caricature and came to realize that "I was much more interested in people thanpolitics." He also couldn’t imagine having to make a point every day, or "that peopleshould be that taken with what I think. Pursuing caricature as a form of portraiturerather than as a type of cartooning came to interest me."

He landed assignments with magazines ranging from Psychology Today to U.S. News & World Report to Esquire and GQ. He won awards and ended up in The Savage Mirror: The Art of Contemporary Character, a 1992 book that described him as "a traditionalist" whose portraits "are as extreme or mild as the subject demands - funny but rarely insulting."

"Kascht will exaggerate a physical feature or a piece of clothing in order to achieve a strong aesthetic effect, but his caricatures are solutions to more formal problems thangraphic commentaries," said the book, which published nine of his caricatures. "His most violent distortion was reserved for Mick Jagger, whose own self-caricatural stance was even further exaggerated by Kascht’s deft hand."

Zach Trenholm, a San Francisco caricaturist, admires Kascht for knowing the boundaries between exaggeration ("being highly satirical") and distortion ("being cruel").

"That’s the hallmark of celebrity caricature - not poking fun at people but expoundingon their image and their fame," Trenholm said. "It’s a very fine line. Somehow he manages to make everyone look glamorous, and that’s not easy to do."

Kascht’s reputation grew with every published caricature (he also still does privatecommissions), and about 15 years ago his work caught the eye of Wendy Wick Reaves, curator of prints and drawings at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. He called her his "champion."

"I thought he was an excellent artist who drew great likenesses and built a lot of subtlety into his work," Reaves said. "It is very discerning and insightful."

She believes his best work involves celebrity caricatures, and she marvels at his ability to execute a portrait "that is not malicious in intent, unlike some caricaturists who express weaknesses and flaws in people, or like political cartoonists who may have an axe to grind." Her favorite Kascht caricature in the gallery is of Whoopi Goldberg: "I love her dreadlocks, tendril-like, and her hands with those long, thin fingers, and the wonderful expression on her face."

"I don't think of caricature as distortion ... It's magnifcation."

The gallery holds 22 Kascht caricatures, including Alan Greenspan and Warren Buffett,both now on display in the "Twentieth-Century Americans" exhibition. Earlier this year, the gallery posted a half-hour documentary, "Funny Bones: Anatomy of a Celebrity Caricature," in which Kascht explains to viewers how he created talk show host O’Brien in pencil, ink, clay and watercolor as well as "in cheese curds, vegetables and breast pocket hankies."

In the film, which Kascht also wrote and narrated, he defines drawing "as the organization of marks on a paper," purposeful or not. "Sometimes my hand will do something and I’ll think, ‘What the hell was that?’ Squiggles and marks just kind of happen, but I know from experience that most of the freshness in a drawing happens from the accidents. A drawing isn’t exactly planned; it emerges as a kind of an artifact of the struggle between what I intended and what I didn’t intend."

He relates the evolution of a sketch to that of a person growing up.

"We all start out as a blank canvas," he said. "From day one, life begins shaping and marking us up. The generic cuteness we’re all born with is gradually replaced by character. Over time, we each develop a unique look according to what we encounter in life. ... We literally wear our lives."

Those who wear their lives at the edge are especially appealing to draw. You won’tfind anyone more wild-eyed than Jack Nicholson or as sneering as Jagger or KeithRichards in Kascht’s caricatures, but he insists he doesn’t set out to distort anyone’s visage.

"I don’t think about caricature as distortion," he said in the film. "It’s magnification.There’s a big difference. It’s precisely because I’m going to amplify someone’s features that I do care about clarity. I want to see them. There’s truthfulness about caricature. What may look like distortion was there to begin with, before I started messing around.

"I scribble where the subject leads me. Sometimes I’m hot on a trail, sometimes it goes cold, but at this stage nothing is a mistake. It all gets me closer. I learn to trust these first impressions. Down the road when I start to get lost in details, I’ll keep myself on track by referring back to them."

The O’Brien film involved much more than Kascht surrounding himself with photos.He studied O’Brien on television, sat in meetings in his New York office and caught his show. He struggled with how to portray O’Brien’s "Rushmore-like head," with its high forehead and pompadour-like hair," and his giraffe-like 6-foot-4 figure. For inspiration, he created a clay mold of O’Brien’s head before settling in to draw the caricature, featuring hair that O’Brien described as softserve ice cream, ever swirling skyward.

"So after a couple of dozen drawings, a few paintings, a sculpture, I discovered whatI already knew: a definitive portrait of Conan O’Brien isn’t really possible," Kascht says in the film. "That’s true of celebrities generally. Everything is fleeting. There’s always a new role, a new look, a new scandal, a new surgery. Always a next act. A celebrity caricature is at best a snapshot of a rapidly moving target. As long as there is something new to observe, it’s never really finished. It’s always a work in progress."

Another memorable encounter was with Katharine Hepburn in 1995. She fascinatedhim and he dropped her a note: "Can I come to your house and draw you?" She said yes, and he reveled in her prickly personality and distinctive features - high cheekbones, strong jaw, imperious nose and "a pile of hair that defied gravity," he wrote in "Drawing Miss Hepburn," published in New York Times magazine.

"Imagine a bird’s nest that has been returned to and expanded upon spring after spring," he wrote. "Or an exploded mattress that someone has tried to stuff back together. Think of a Gibson girl caught up in a windstorm. The fascinating illogic of her hair would cause me trouble for the next day and a half. I began to delineate its basic architecture, the first of many doomed efforts."

He also fell in love with "that fantastic antique car of a voice, its motor forever straining to turn over another syllable." As he slips into a spot-on imitation of her, one is awed at the way he brings her to life with his voice as well as his sketches and writing.

Kascht is equally skilled at discerning political candidates. Three years ago, he createdthree-minute films on seven presidential candidates for the Washington Post, drawing caricatures as he narrated his script. Concluded the Post in describing his "Candidates 101" series: "Kascht makes a good case for looking as a means of gathering reliable information about our public figures."

It takes Kascht two or three days to complete a caricature, working in the chicken coop studio or a studio on the third floor of his farmhouse. As he did with the off-the-cuff Obama caricature, he scribbles basics of a likeness at the outset and adds layers before scanning the sketch into his computer and printing it at the right size. He sets the printout on a light table and traces it to a watercolor board, where he paints it.

It takes Kascht two or three days to complete a caricature, working in the chicken coop studio or a studio on the third floor of his farmhouse. As he did with the off-the-cuff Obama caricature, he scribbles basics of a likeness at the outset and adds layers before scanning the sketch into his computer and printing it at the right size. He sets the printout on a light table and traces it to a watercolor board, where he paints it.

"You know that expression, ‘Capture a likeness’?" he asked. "I love that expressionbecause it describes a hunt. There are days I’m chasing people all over the place."

A self-described "night owl," he also can get so wrapped up in his work that he loses track of time and sense of place, semiconsciously shedding his clothes. "A lot of times I’ll end up sketching in my underwear," he told a National Portrait Gallery audience last December. "It just happens."

And he pokes fun at himself when asked about his goatee and pony tail: "You mean, when did I become a caricature of an artist?"

By the end of a caricature, Kascht finds he has lost his objectivity, if not his patience, because he is ever the perfectionist.

"All I can see when I look at it is all of the things that didn’t work out the way I had hoped," he told the gallery audience. "I can’t wait to start the next one, and the nice thing about that is I do generate enthusiasm for the next assignment because I think I am going to redeem myself."

As successful as Kascht is, he worries about the future - everything from his nextcommission to the uncertain future of magazines and newspapers, which have publishedmany of his best-known caricatures, to whether caricature can sustain itself as an artform on the web.

He sees unlimited potential in the latter, and this fall he became the second artistfeatured in the "Above and Beyond" series designed for iPads. The interactive book includes 50 of his caricatures, and with a tap of a finger you can see the evolution of each portrait from initial pencil sketches to finished product and listen to him describe his thought process. The first "Above and Beyond" book featured National Geographic photographer George Steinmetz, who shot aerials from a motorized hang glider.

Throughout an interview and dinner conversation that ran for more than eight hours, Kascht parries questions about naming his best - or his favorite - caricature. He can’t seem to decide. He is fond of the David Lettermen and Woody Allen caricatures in the National Portrait Gallery, but as he flips through his work he mentions Seeger ... then Murray ... then Jagger ...

"How about the next one?" he asked.

Find more of Kascht at his website or download an iPad book detailing his work.

Read more from St. Thomas magazine