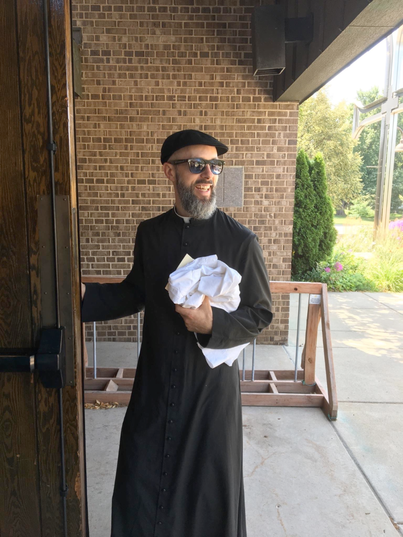

Father Kyle Kowalczyk ’16 CSMA/M.Div.

The Church of the Epiphany, Parochial Vicar

What happens when you put a hillbilly, a poet-comic, a thespian and a jazz musician on a diet of standard Catholic studies fare – Aquinas, Chesterton, Woytla and all the rest?

The church gets four spectacular vocations to the priesthood.

“I was studying theater when I first felt the call to the priesthood,” says Father Andrew Thuringer.

“I was playing the father of a family in crisis in Neil Simon’s “The Brighton Beach Memoirs,” when God began to tug on my heart. It was like he was saying, ‘Look, this is the priesthood. You have no business being a father to these people, but it’s the part the director has cast you to play.’ As a priest, you’re constantly humbled by your unworthiness and yet God has cast you to play a particular part in his great drama of salvation.”

Father Kyle Kowalczyk, who wrote “Why Priests Must Be Poets” as his master’s thesis, recalls a similar connection. “It was startling to me when the desire to do theater started coming back in the one place in which it seemed impossible to fulfill – seminary!” While at Saint Paul Seminary (SPS), his passion for theater was reignited and, while there, he wrote, directed and acted in the SPS Theatre production, “Moonshine Abbey” (among other productions). “It came alive in a very new way. In the past, I just enjoyed making people laugh … But now with years behind me, a more well-formed mind, and real faith life, it took on a whole new meaning. Although laughter was still part of it, it became an opportunity to get people thinking about real issues – faith issues.”

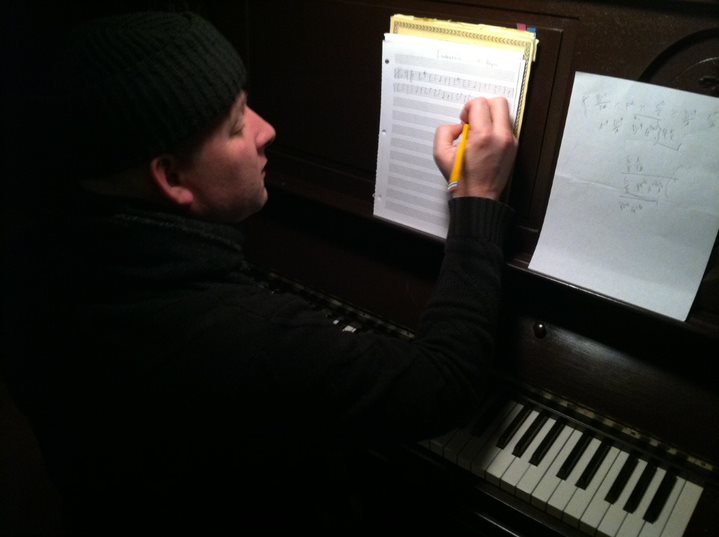

Father Byron Hagan ’11, ’15 M.Div.

BA Philosophy, Latin, and Catholic studies

Holy Cross Catholic Church, Parochial Vicar

Musician and composer Father Byron Hagan’s road to the priesthood first involved his conversion to Catholicism, and then the long discernment that is seminary, entering SPS at age 40. He says his four years in Catholic studies was like installing “a standard operating system for my soul. Everything I do assumes it and is powered through it.”

Hagan spent the first 20 years of his professional life working as a musician and composer, recording and traveling the world with various acts. His freelance occupation, he remembers, gave him a lot of time to read philosophy, theology and great literature. When he found his way to writers like G. K. Chesterton, his conversion to Catholicism wasn’t far behind. He recounts The Everlasting Man as a tour de force narrative of Western culture in the encounter with Christ.

Upon reading, he thought, “If Catholicism gives the mind this sort of power, then I might need to investigate the religion a little further. ‘Art is fundamentally a search,’ he says, ‘long before it is “self-expression.” I had to learn that art and the artist life becomes a prison, an empty promise, when consciously divorced from the context of a broader spiritual culture that the great tradition gives to us.’ He continues, ‘A major turning point in my journey to the Catholic Church came when I decided to begin writing music that my father would like. My father isn’t just someone I love. He’s a good man and his artistic values are both sophisticated and wholesome and they harken back to an older tradition, when the striving, self-aggrandizing temptation of artists was tempered by a tradition that asked them to be servants of the common good. For a long time I didn’t care about the second thing but only the first, and I was thinking more about creating myself through music rather than learning about myself. I eventually discovered that we can miscreate ourselves, because there’s something prior about who and what we are and we can choose to be obedient or not to a nature that is already created in us by God, that he made good, that he wants to make whole. We have to step into this, and this means a way of life that gives up illusions and self-deception and is willing to live in the truth.”

Father Andrew Thuringer ’13, ’17 M.Div.

BA Philosophy, Minor Catholic studies

St. Mary Church, Associate Pastor

Father Austin Litke, one of the founding members of the Hillbilly Thomists, a group of Dominican bluegrass musicians, recalls that, “In Catholic studies, the study of literature, art and music played a completing role in our formation. I continually returned to them, seeking out a continued study of poetry and music in particular as a means of deepening and expanding my study of theology.”

Particularly as expressed in the liturgy.

“As a Dominican friar,” he says, “the daily solemn celebration of the liturgy is an essential element of my vocation and life as a friar. I’ve found that liturgy well celebrated has the ability to draw the human heart in a way that rational argumentation cannot.”

“Even in the midst of scandal,” says Litke, “I have found that people generally look to the Church and to the priest as her representative for meaning in the midst of suffering or loss.”

And while performing arts might open a window to God, Thuringer is quick to remind us that the priesthood is anything but theater.

“As a priest,” he says, “I’m not acting at the altar. It’s tempting to make comparisons between the Mass and the theater, but they’re very different. And I can honestly say that as a priest those differences are even more obvious to me than before. I’m not performing or pretending up there. Celebrating the Mass is the most real thing I do every day.”