University of St. Thomas engineering professor John Abraham, a globally known expert on climate change, is on a quest to make the world a better place. That quest begins in his very own backyard.

When Abraham invites visitors into his south Minneapolis backyard, guests may first notice the large vegetable garden. But after looking up, they’ll find themselves immersed in a sort of solar panel heaven. Panels adorn the home’s roof, and even more glimmer on the property’s detached garage.

Solar energy powers his home and his cars, even in the middle of a Minnesota winter. In fact, he hasn’t paid for gas or electricity in years.

“I live the message of clean and renewable energy in my daily life,” Abraham said. “It saves me money and it saves the environment at the same time. That’s a win-win.”

Abraham can’t resist a win-win, especially when it comes at the intersection of energy and climate. He’s spent much of his professional career – as a researcher, professor and engineer – searching for solutions to some of the world’s most pressing problems.

An expert in the thermal sciences – basically anything that has to do with heat or energy flow – Abraham joined the School of Engineering in 2002. His expertise allows him to teach core engineering courses, such as heat transfer and thermal design, but it has also led to his rise as one of the world’s most respected researchers on climate change.

Renowned climate researcher

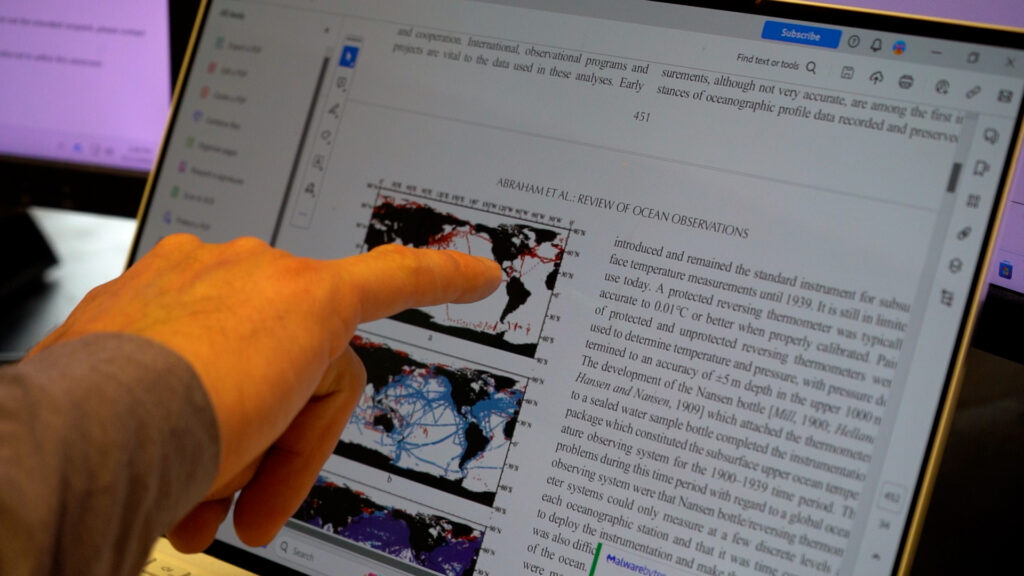

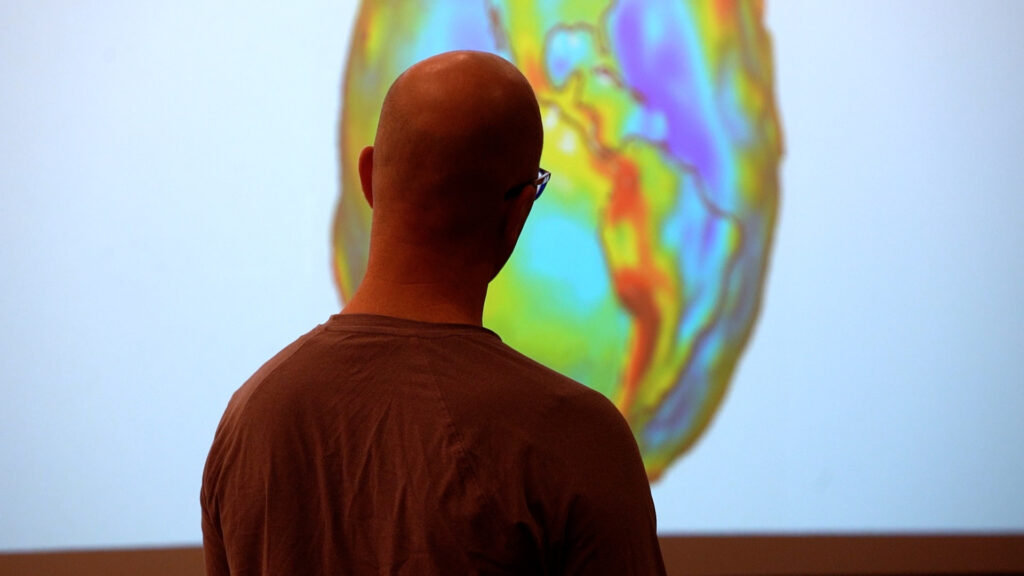

Each January, Abraham and a team of more than 20 international scientists deliver a report on the temperature of the planet’s oceans – a key metric in monitoring global warming. Since 2017, their annual report card has shown ocean temperatures soaring to alarming new heights.

“Over 90 percent of global warming heat ends up in the oceans,” Abraham said, “So if we want to know how fast the climate is changing … the answer is in the ocean.”

To take the ocean’s temperature accurately, the team hires contractors to drop hundreds of small torpedo-shaped probes all over the globe. Abraham then monitors the data from his office in O’Shaughnessy Science Hall on the university’s south campus. He isn’t shy about sharing.

“My students are getting the data as it comes out of the oceans, so we know in real time what’s happening in the environment,” Abraham said. “It’s incredibly exciting to have a direct connection in your classroom to what’s happening in the real world.”

Of course, Abraham hardly contains his findings to the classroom – he’s an in-demand guest on news programs near and far, regularly appearing on the BBC and CNN. He’s also a go-to expert for The Guardian and Washington Post, giving updates on the planet’s health.

“We publish this data because it’s important for our society to know and understand,” Abraham said. “If we want people to make smart decisions, to change the way we get energy, power our vehicles and our homes, we need them to know what’s happening with our climate.”

New Zealand-based researcher Kevin Trenberth, who is a co-author of the annual study and works at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, says Abraham has played a key role in delivering their findings to a wider audience.

“(With our) annual update on the ocean state and warming … John has been very keen on these … insisting on helping write the first draft, and thereby sets the outline for the paper’s thrust,” Trenberth said. “This research is at the forefront of the advances being made in detailing what is happening within the ocean and the climate system.”

Engineering for the world

Knowledge is power, but to truly create a healthier, more sustainable world, physical change must come with it. And that’s where Abraham’s expertise delivers a knockout “one-two” punch.

Back at his home in south Minneapolis, visitors who take a trip inside are greeted by evidence of a more global quest to solve problems. African artwork adorns the living and dining rooms, cherished pieces that reveal just who this family is at heart.

Abraham first visited Uganda as part of a St. Thomas engineering project to provide solar power to a small, remote village. Falling in love with the country, he’d quickly return with his wife to adopt one of their daughters.

In the years since Abraham has doubled down on sustainable design projects for developing countries in Africa. To do it, he’s involved an ever-growing list of St. Thomas engineering students.

Brian Plourde ’11 visited Uganda, Kenya and Cameroon with Abraham in 2014. The moment would change the course of the graduate student’s budding career.

“We were studying how different technologies impacted local culture, and we saw people get their first light bulb,” Plourde said. “Right from there, John and I literally mocked up a technology path that could impact those communities.”

One of the biggest issues in the developing world: a lack of clean drinking water. Together, Abraham and Plourde worked to establish a new company, LEMA, which would tackle the issue. They’d soon develop a groundbreaking device that uses the sun’s energy to pasteurize water, making it safe to drink.

“Working with John, we’ve learned to collaborate like family members,” Plourde said. “John has been an integral part of the technology development of LEMA, but he’s also played an important role in my development as a person and engineer.”

Powering an optimistic future

Students solving societal problems sustainably, and making a career out of it, is the ultimate win-win for Abraham as an engineering professor.

“When we can teach students how to advance their careers in high-tech industries … while saving the planet … and while saving money … that’s what I love most about teaching at St. Thomas,” Abraham said.

LEMA Water has since rolled out in countries across the world. And the company has expanded its impact, debuting off-the-grid technologies to power hospitals, farms and community centers.

“Our students at St. Thomas are hungry. They want to take the skills they’ve developed in the classroom and bring them to the real world and make that world a better place,” Abraham said. “It’s beautiful to help make those connections, and so exciting to watch the light bulbs turn on in their heads.”

That light helps balance the darkness that often comes with staring down the world’s most pressing problems.

For the eighth year in a row, Abraham’s international oceanic research team is preparing to deliver bad news at the beginning of 2024. The earth’s oceans are still warming at an alarming rate. And yet, Abraham remains optimistic.

“We have reached a tipping point in technology – you can save money and the environment at the same time,” Abraham said.

That’s certainly apparent in Abraham’s own backyard, where he now makes money from his solar investment. Xcel Energy sends regular checks for all the extra power he produces.

An engineer at heart and professor to many, Abraham firmly believes critical solutions are arriving with each new day, and his students will be happy to fill in any gaps.

“Engineers are problem-solvers. We look at the world, and use our technical know-how to solve those problems,” Abraham said. “There are a lot of reasons to remain hopeful.”