In 1989, the Pritzer Prize, architecture’s equivalent of the Nobel Peace Prize, was given to architect Frank Gehry for his “refreshingly original and totally American” buildings. The University of St. Thomas is now home to Gehry’s innovative and playful Winton Guest House (1982-1987), located on the Gainey campus in Owatonna; however, Gehry is not the first exceptional architect to be involved with the institution.

From the inception of St. Thomas, we have had pre-eminent designers complete buildings that are important to the history of American architecture, including Clarence Johnston’s Chapel of St. Mary (1905), Emmanuel Masqueray’s Chapel of St. Thomas Aquinas (1918), and Edwin Lundie’s Gainey House (1954-1957). But, perhaps the most notable work completed for St. Thomas was done by turn-of-the-20th-century architect Cass Gilbert.

The year is 1890. The high school, college and seminary of St. Thomas Aquinas, founded by Archbishop John Ireland, have been holding classes for five years in a single, Second Empire style building located on the site of the present day north campus. The time had come to consider a more elaborate setting, given the expanding interest in religious training at the seminary.

Ireland had the land, 60 acres donated by Irish immigrant William Finn. He needed an architect and patron to create and finance his vision. The patron? None other than railroad baron James J. Hill, who would contribute $500,000 to the project in honor of his devout Roman Catholic wife, Mary.

As historian Mary L. Wingerd noted in Claiming the City: Politics, Faith and the Power of Place in St. Paul (2003), Hill had a vested interest in the seminary for business reasons as well. Archbishop Ireland was committed to the Americanization of Minnesota’s culturally diverse Catholics, and his goal was to establish a seminary that would train priests to impart American Catholic principles to their parishioners. Since most of Hill’s employees were Catholics, it served his purposes to support the education of priests who would Americanize his workforce. It also served Hill’s purposes to recommend a capable designer to the archbishop.

On Oct. 22, 1891, James J. Hill summoned Cass Gilbert to his imposing new residence on Summit Avenue. Gilbert, a graduate of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Ecole des Beaux-Arts based architecture program, had worked in the office of the most important architecture firm in late 19th century America, McKim, Mead and White, before returning to St. Paul in 1882. A six-year partnership with James Knox Taylor dissolved about the time of this particular meeting.

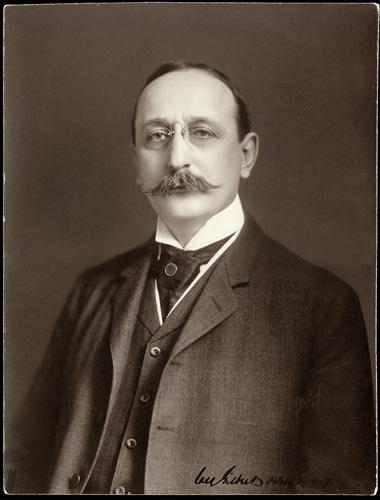

Cass Gilbert. (Photo courtesy Minnesota Historical Society)

Gilbert’s career was taking off and Hill had been the benefactor of his success in Gilbert’s designs for several depots for his Great Northern Railway. When Gilbert arrived at Hill’s mansion, he found Archbishop John Ireland and Father Louis Caillet (Mary Hill’s confessor) there with his host. The purpose of their meeting was to discuss the design of new buildings for the expanding seminary. The next day, Gilbert and Archbishop Ireland drove out to see the land Ireland had selected: forty wooded acres sloping toward the east bank of the Mississippi River at the end of Summit Avenue.

Archbishop Ireland contributed to the seminary’s design as much as he could, but Hill left no doubt that he was the one who was fully in charge. Gilbert historian Geoffrey Blodgett described their encounter in Cass Gilbert: The Early Years (2001): Hill “fixed his intimidating one-eyed glare on the young architect and told him that he was answerable to Hill, not the archbishop, on all issues touching design, construction, and cost.”

Hill’s continuous intervention into the minutia of everything from heating systems to door locks must have challenged Gilbert. He regularly gave the architect a dressing-down if the slightest changes were made without his approval; and he even threatened to find someone else to work with or to stop work altogether.

Gilbert seriously considered withdrawing from the project more than once, but he saw it through to the end.

Despite the power struggle with Hill, Gilbert succeeded in producing an environment that supported Ireland’s goals: a place for the education of American priests with a campus that engaged with its natural environment and developing residential area around it.

Gilbert designed six buildings for the seminary: an administration building, a classroom building, two dormitories, a refectory and a gymnasium. The original plans called for a chapel as well, but this was put on hold until later. Hill wanted the buildings to be plain but dignified. Gilbert responded with a pared-down aesthetic similar to the Great Northern depots he had already designed for Hill in Willmar, Grand Forks and Anoka, a safe choice since their design had already weathered Hill’s exacting scrutiny.

As Hill kept pushing Gilbert to reduce costs, the architect drew together Renaissance inspired elements to produce well-proportioned buildings with smooth brick walls, hipped roofs and arched windows. The north and south wings of the administration building housed, respectively, a private chapel and a library large enough for 20,000 volumes. The three stories of the central portion housed administrative offices, apartments for professors, a common room, parlors and reception rooms. At four stories plus the attic, the north and south dormitories each had a chapel, and together they provided enough space for each of 120 students to have two private rooms. There also were bathrooms with hot and cold water and an infirmary.

The St. Paul Seminary building, now demolished. (Photo courtesy Minnesota Historical Society)

In the two-story classroom building there were four classrooms, one of which was a “physical” and chemistry laboratory. On the second floor there was a “great hall” (also referred to as the aula maxima) with a platform at the front and seating for as many as 500 people, a space that served the community as well as seminary.

The two-story refectory housed a kitchen and dining hall described by a contemporary writer as having a “lofty ceiling of native woods, broad, old time fire place, plentiful supply of light.”

From the outside, the most notable feature of the gymnasium building that doubled as the school’s heating plant was its smokestack, complete with a Latin cross in brick relief at its uppermost reach. For recreation, the two story structure offered a large gymnasium with open trusswork and four smaller rooms, one of which was used for reading. Although the 1893 financial panic slowed things down, the buildings were completed in 1894 at a cost of $184,268.13, well under the $200,000 budget, as Gilbert was proud to point out — and even then Gilbert had a hard time getting Hill to pay him in full.

In an article in the April 1895 issue of the Catholic University Bulletin, Father Patrick Danehy, one of the seminary’s professors, described the new buildings as being “in the North Italian style, simple, solid and impressive.” To him, “the solidity of their walls reminds one strongly of the monastic edifices of a bygone age.” For Archbishop Ireland, on the other hand, the seminary was meant to be contemporary and forward looking, designed to meet the latest needs of the modern, American Catholic Church.

Even with its nod to tradition, the facilities the seminary provided were fully up-to-date, from a heating plant that was reportedly so advanced that it was written up in the Engineer’s Journal, to a physics and chemistry laboratory designed to make sure the students would be well-informed when questions came up about the relationship between science and religion.

The campus also was decidedly unmonastic. Rather than clustering the buildings tightly around an inward-looking, cloister-like courtyard, Gilbert oriented all of them northsouth and grouped them loosely, leaving a good bit of space between them. He also oriented them so that they would have a connection with the surrounding community.

Summit Avenue skirted the northern boundary of the site, and the east-west trajectory of Grand Avenue defined the campus’ main axis. This became all the more apparent when a drive – essentially an extension of Grand Avenue – was installed through the center of the court. The campus was thus connected with and open to the community, and it also provided a reason for people to come: the classroom building housed an auditorium that could seat as many as 500 people for public lectures.

Ireland’s decision to place different functions in separate buildings was an unusual choice at a time when most seminaries were housed in a single, large building. Ireland believed that seminary education ought to cultivate the body as well as the mind and spirit, and he contended that exercise should be part of the students’ education.

Ireland may have been responding to growing concerns about seminarians being too stationary and disconnected from the world, as they remained holed up in the large, all-purpose buildings where they lived and typically were educated. And he also may have imbibed the growing taste for “muscular Christianity,” a movement that advocated physical exercise as a means to the production of a form of Christianity that was robust and manly.

Physical education was becoming an increasingly important component of education, as Gilbert would find in designing buildings at the Shattuck School in Faribault, Minn., and Madison Central High School. With the campus-like arrangement Gilbert produced, the students would be compelled to get outdoors to go from building to building, and they also would have the gymnasium available for more vigorous exercise. Beyond this, there were acres of what Danehy described as “native sward threaded with graveled walks and dotted with flower beds” where the seminarians could stroll.

The result was a campus designed to produce a new, American priesthood, through modern facilities serving a modern educational agenda, encouragement of physical as well as mental exercise, and integration with the community.

Perhaps Gilbert's most iconic Minnesota design is the state capitol building.

By the time the seminary was ready to build its chapel, Gilbert had extricated himself from the project and moved to New York. He may have been relieved rather than offended when his architect friend Clarence Johnston was tapped to do the chapel’s design. Predictably, the seminary was known, for a time, as the Hill Seminary after its major benefactor, and its resemblance to Hill’s Great Northern railroad buildings was not lost on observers.

What remains of the St. Paul Seminary is now part of the University of St. Thomas’ south campus. Three of the buildings have been demolished and several still serve the university community. The two dormitories – Cretin and Loras halls – have been remodeled, with the former an undergraduate student residence and the latter an office building. The gymnasiumheating plant survives as the university’s Service Center, although at one point it was considered as a potential dedicated art gallery for exhibitions, a notion that may come to be in a new fine arts building in the coming years.

In To Work for the Whole People: John Ireland’s Seminary in St. Paul (2002), author Sister Mary Christine Athans noted that designing and overseeing the construction of the Minnesota State Capitol (1895-1905) or even the United States Supreme Court Building (1928-1935) in Washington, D.C., probably was an easier task for Gilbert than building the seminary.

Even though Gilbert at times was constrained by Hill’s patronage, he stayed true to his classically inspired architectural vision and created at the end of Summit Avenue, the start of our own version of an American architecture, appropriate to the Catholic identity of those creating it.

About the authors: Victoria Young is an associate professor of modern architectural history at St. Thomas. Katherine Solomonson is an associate professor of architectural history in the College of Design at the University of Minnesota, and is working on a book documenting Gilbert’s career.

Read more from St. Thomas Magazine.