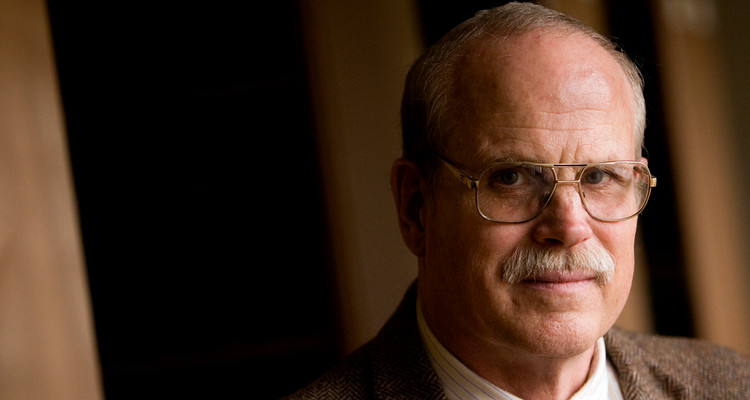

I have been asked to write something on Terry Nichols’ life for the new departmental newsletter. I agreed to do it, under the following conditions: it would be selective and make no claim to finality (in the event, I have relied on information in Terry’s c.v.; on conversations with Mabel Nichols, his wife, and their son Peter; and on my own two decades of friendship and collaboration with Terry); next, it would be a personal sketch of Terry as I knew him; third, it would make just passing reference to his published writing, most of which deals with topics outside my own expertise as a church historian, and which have been ably treated by other theologians in the retrospective on his work held at St. Thomas on September 23, 2014; and fourth, it would give more attention to his background and life prior to working at the University of St. Thomas.

FAMILY OF ORIGIN

Terry was the older of two children born to Howard “Nick” and Elaine “Tede” (Godward) Nichols. He was born on January 29, 1941, and his sister Gaydon Nichols followed two years later. His father was a self-made man, a guy blessed with high intelligence and exceptional physical strength, to go with intense and burning ambition—all qualities that Terry inherited. Nick Nichols put himself through college and graduated from the University of Minnesota in the middle of the Depression. He met Tede while they were both students at the “U” and he resolved immediately to marry her. Family lore has it that her family, who represented the upper crust in the tony suburb of Edina, never quite accepted Nick, despite his success as the owner of a company that built and maintained power plants in Minnesota and the upper Midwest. It does not seem to have been an easy family in which to grow up: there was some alcoholism to deal with, and Terry talked often about his dad’s daunting stature—though I never heard a word about his mother. He himself was treated as a bit of a golden boy and a prodigy, skipping third grade and graduating from Edina High School in 1958 at the age of 17.

YOUTHFUL STRESS AND MATURATION

He wanted to attend Carleton College here in Minnesota, but when Harvard offered a scholarship, his family persuaded him to accept it. This was a time, the late fifties, when the Soviet success at space exploration had sent American higher education into a panic over the state of scientific education. Elite schools like Harvard resolved to reduce their “legacy” admits and look for the brightest men (coeducation in the Ivies was still several years away), and SAT scores were the main benchmark. As Terry used to say ruefully, the result was an influx of very bright and very unbalanced geeks. As is well known, one of his classmates was Ted Kaczynski, the future “Unabomber” (Terry said he never met him).

His education at Harvard, where he was majoring in chemistry, ended in spring 1960 after two years of falling grades and serious emotional difficulties. The precise nature of this crisis remains elusive. A doctor who examined him later gave a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Although the doctor recognized that Terry’s symptoms did not really fit the diagnosis, he gave it in lieu of anything else, partly to forestall the possibility that Terry might be drafted (the Vietnam War was heating up, and more and more Americans were being drafted into service). Military service for someone in his fragile emotional condition would have been a disaster. Schizophrenia it may not have been, but certainly some acute form of depression, which he would struggle with the rest of his life. I remember an episode just four years ago, when he admitted to me he was so down that he thought he might have to leave teaching.

After withdrawing from Harvard, later in 1960 he made his way to San Francisco, where he lived and worked for four plus years delivering newspapers and harvesting grapes in a vineyard in the Napa Valley owned by his uncle Bud Godward. By January of 1966, he was back in Minnesota and ready to resume his college education at the U. He graduated a year and a half later with a major in humanities and a special interest in poetry, including courses with the poet John Berryman.

FAMILY LIFE: HUSBAND AND FATHER

At the same time he was earning his deferred bachelor’s degree, he was losing his bachelor status. Shortly after classes began in January 1966, he met his future wife Mabel, then a nun, at the University’s Newman Center. They fell in love and were married the following year. Three children followed: Theresa (1967), Michele (1969), and Peter (1976). In immediate need of a job, he worked from June 1967 to March 1968 delivering mail for the Postal Service. Family life did not cure his restlessness—nothing ever really would, not perhaps until the last year of his life—and in the spring of 1968, he borrowed money from his dad, bought a Volkswagen camper van, and set off with wife and infant daughter for four months in Europe. They toured much of western Europe, living cheaply (this was the postwar Europe of “Europe on Five Dollars a Day”), staying at campsites, and at the end sold the camper for $2000 less than they paid for it.

Back in the U.S., he got a job with another uncle, Pep Godward, who had a waterproofing business. After two years, he decided to strike out on his own and, in partnership with a guy named Bill Hines, whom he’d met at the U in a chemistry class when Terry needed someone to take notes in his occasional absence (Mabel says that he always admitted sheepishly that he coaxed her to ask this person to take notes), he went into the roofing business, which would last a decade (1972-1982). During this time, he also fulfilled a long-standing ambition to build his own house, the remarkable octagonal home outside Cottage Grove in which the Nichols family has lived since 1975, on land Terry and Mabel (characteristically) believed they were able to buy only because of a providential turn of events. The roofing business finally ended when Terry acted on another long-cherished ambition to go back to school for an advanced degree, not in chemistry or in literature, but this time in theology.

BECOMING A CATHOLIC

Terry had been raised as an Episcopalian. Although he was baptized hurriedly as an infant—he was the only infant in his ward of newborns to survive a siege of viral pneumonia—religion never played much of a role in his family’s life, and he apparently had a phase as an atheist after he went away to college. At Harvard, he encountered the remarkable figure of the Dominican friar and published poet Brother Antoninus, O.P. (1912-1994). Born William Everson, Brother Antoninus was a declared pacifist during World War II and, like many in the postwar religious ferment, in 1948 converted to Catholicism. In 1951, he joined the Dominican order as a lay brother and took the name Brother Antoninus. At the same time, he was rising to prominence in the San Francisco Renaissance as a poet, a literary critic, especially of the poetry of Robinson Jeffers, a master printer (he produced fine work with a handset press and founded Albertus Magnus Press), and by all accounts, a charismatic preacher and lecturer. Terry told me that Brother Antoninus was the person most responsible for bringing him into the Catholic church. Antoninus’ return to the Dominican Priory in Kentfield, California, may have been a factor in Terry’s post-Harvard move to the Bay Area, and it was there that he was baptized into the Catholic church on June 18, 1965. No one seems to know why Terry chose to be baptized again, since it seems unlikely that there was anything about his infant baptism as an Episcopalian that the Catholic church would not have accepted.

When I asked Mabel Nichols how she felt about Terry’s desire to get an advanced degree in theology, she told me she supported it wholeheartedly, even though the closest Catholic doctoral program was hundreds of miles away at Marquette University in Milwaukee. They had been very active during the 1970s in the Catholic charismatic prayer movement, which seemed to offer to them a richer and more vital form of religious life than was available at the local parish. Eventually, though, they both became disenchanted with the anti-intellectual and authoritarian tendencies in the movement and withdrew from it.

Mabel thought theological study was worth the stress of a three-year program and a long-distance commute. Terry bought a house in Milwaukee, paid for it by renting rooms to other students, and commuted home every third weekend when the university was in session. Mabel held the fort, not just caring for three children, all by then in school full-time, but also running the imported clothing store on Grand Avenue in Saint Paul that she had started already in 1978, after a trip they had taken to Guatemala. The original idea for the store was to provide an outlet for woven goods from the Catholic mission at San Lucas Tolimán, where Minnesota priest Fr. Gregory Schaffer (1934-2012) had started an array of social service initiatives in 1962. The Grand Avenue store (which, please understand, is wholly Mabel’s work) is an early example of the kind of practical service venture that Terry liked to start—and then to entice/nudge others into sharing. Casa Guadalupana, the Catholic Worker Hospitality House for Latina women and their children that he started on Saint Paul’s West Side, would be a later example.

BECOMING A PROFESSOR:

GRADUATE EDUCATION AND LIFE AT UST

Terry took three years (1982-1985) to complete his course work at Marquette. He tackled graduate education with the laser focus and intensity that marked everything he did. He seems to have most appreciated the intellectual sophistication of academic theology, which was like water in the desert after years in business and in the charismatic prayer movement. He especially enjoyed the historical courses and his explorations into non-Christian religions. After passing his exams, he returned to Minnesota, where he wrote his dissertation and was awarded his doctoral degree in 1988. The dissertation, “Miracles as a Sign of the Good Creation,” with Philip Rossi, S.J., as director, signaled two enduring features of Terry’s religious sensibility: the experiential reality of the supernatural, and the compatibility of faith and reason.

He started teaching at St. Thomas in 1988. A dissertation on miracles was probably not an easy sell to the department, and oral tradition has it that there was resistance to hiring someone who was not only a latecomer to academic life but conspicuously devout. The polarization that has marked Catholic life for decades now probably prevented some from recognizing that Terry was never a dogmatic authoritarian, but someone who lived by and for argument and learning, and someone who was always open to what experience might tell him, even if it unsettled previous patterns of thought. It is true that the metaphysical framework within which he worked was a version of Thomism, whose realism seemed to him the best philosophical vehicle for adjudicating relations between theology and science, one of the three areas that dominated his teaching, writing, and service. But he always stressed that his was a critical realism in the epistemological sense taught by Bernard Lonergan, with an openness to history and development that does not come easily to Thomism.

Once hired, his progress at St. Thomas was steady: from full-time but limited term in 1988; to tenure-track and tenure as associate professor by 1997; to full professor in 2003 until his anticipated retirement in 2014, with multiple forms of university and non-university service to show for that time, punctuated by three books and numerous articles, and courses in diverse areas of specialization, from religion and science, to the afterlife, to ecclesiology, to environmentalism, and to Muslim-Christian dialogue. His service included four years as chair (2002-2006) and as the founder and co-director of the Muslim-Christian Dialogue Center. Administration was not his strength, he knew, but he did it when no one else seemed fit or willing. He liked to say, “The worst thing they [the administration] could ever do to me would be to make me chair again.” But he was an outstanding advocate of theology and the department, representing it before the rest of the university community, even its most secularized elements which eventually recognized his intellectual seriousness, his honesty, and his fair-mindedness. In general recognition of his exceptional service to St. Thomas, in 2008 he was given the John Ireland Presidential Award. And as a final and fitting expression of gratitude, the University honored him with a funeral mass on campus on April 16, 2014.

INTER-RELIGIOUS DIALOGUE AND THE MUSLIM-CHRISTIAN DIALOGUE CENTER

I have left to last the creation of the Muslim-Christian Dialogue Center (MCDC), which he founded in 2006, after President Fr. Dennis Dease expressed the wish for such a project as a response to the rather hysterical climate created by the attacks of September 11, 2001, and our subsequent wars in the Middle East. Terry knew we lacked essential academic resources for such work, but he thought we should try it nonetheless, at least in the form of local dialogues with the growing Muslim community in the Twin Cities. For him, such dialogue came out of previous years of ecumenical discussion with separated Christian communities both here and nationally. Because the MCDC is still a work in progress, it is inappropriate to say much at this point, other than to be grateful to Terry’s characteristic courage to take on something risky and new. He was always the entrepreneur.

The most dramatic example of that is his willingness to undertake international inter-religious dialogue with Sunni scholars in Turkey and Shi’ite scholars in Iran. Both ventures, underway since 2011, are ongoing, and their final fruits are of course unknown. But for those who took part in them, they were memorable experiences of crossing boundaries, in the kind of spiritual exploration that Pope Francis has seen fit to endorse and encourage, as the right and natural work of the church in the age of globalization.

As indicated above, I spoke with Mabel and Peter Nichols as I was preparing this sketch, and I want to express my thanks for their generous help. Mabel has asked to include these words of hers, which make a fitting epitaph on his life, from the person who knew him best:

“There were three overriding themes to Terry’s life: his great passion for learning, his strong sense of mission (that God had a work for him to do and he needed to accomplish it), and his lifelong quest for the experience of God’s love. He fought many demons throughout his life, but in the end he triumphed over them. He was never sure he had done what God asked him to do but he thought maybe it was the work with the Muslims. He did feel at the end of his life that he had finally found God’s love. From a place of despondence, anger, isolation and abandonment as a young man, he came at the end of his life to a place of peace and gentleness, loved by everyone who knew him.” —Mabel Nichols

Michael Hollerich is a professor of church history, and has taught at the University of St. Thomas since 1993.

From “theology matters,” a newsletter of the Department of Theology. Subscribe here.