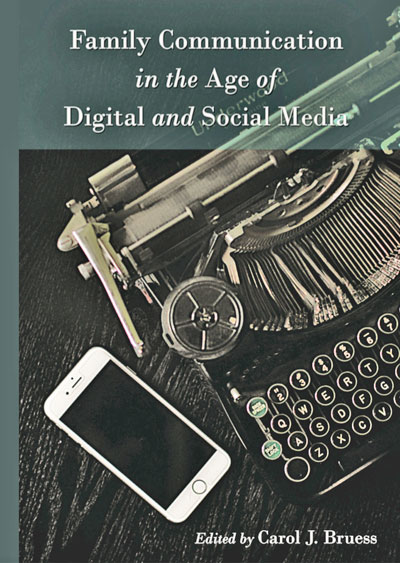

How the digital age is changing families – for good or for ill – is the focus of a just-released, 503-page volume edited by University of St. Thomas professor Dr. Carol Bruess, director of the university’s Family Studies Program and author of five books on interpersonal communication.

Her Family Communication in the Age of Digital and Social Media, published by Peter Lang International, is a collection of essays by social-science scholars who share their latest research and theories on how the widespread use of social media is affecting family relationships.

Bruess and one of the book’s contributing authors, Dr. Meg Wilkes Karraker from St. Thomas’ Sociology Department, will discuss the book and its primary findings at a brown-bag gathering from noon-1 p.m. Tuesday, Dec. 1, in Room 100 (the Great Room) of McNeely Hall on the university’s St. Paul campus. The event is free and all are welcome.

After three years of working on the book, Bruess says “the jury is still out. We’re in the middle of a great big human digital-age experiment.

“What the research tells us right now is that our digital tools are just that: tools. We can use them for good. Or we can use them for harm. As a researcher who loves studying healthy families and marriages, I’m of course advocating for people to use their digital devices to connect with others and make their families and relationships stronger,” she said.

A total of 48 authors contributed to the book’s 22 chapters. Family Communication in the Age of Digital and Social Media is one of a series, titled “Lifespan Communication: Children, Families and Aging,” being published by Peter Lang International. Chapters explore communication among couples, families, parents and adolescents as their lives are impacted by cellphones, smartphones, desktop and laptop computers, MP3 players, e-tablets, e-readers, email, Facebook, photo sharing Skype, Twitter, SnapChat, blogs, Instagram and other emerging technologies.

The book is written for family professionals, graduate students and other researchers. However, each chapter offers an advice section that can help readers make smart choices that foster healthy, digital-age relationships.

“The advice sections are my favorite parts,” Bruess said. “For example, Brandon McDaniel has been studying and reports in the book how couples often allow technology to interfere in their daily lives … even their dinnertime or end-of-day conversations. He calls the problem ‘technoference.’

“His advice to all couples is to do an honest self-assessment of daily technology use, and do a type of personal inventory. He offers questions for individuals and couples to use and reflect on, such as: At what times and how often do I use technology throughout the day? What is driving me to check or respond to my technology?’ Is there any aspect of my use that is affecting me negatively? (For example, does my partner seem hurt or distant when I get on my device?) Is my technology use changing or replacing parts of my real life that were going well before? (For example, I used to talk with my spouse every night before going to bed and felt closer to him or her, but now we are often both on our tablets even when we climb into bed.)”

Most of today’s forms of social media didn’t exist when Bruess received her Ph.D. from Ohio University’s School of Interpersonal Communication in 1994. “When I was at Ohio University in the early 1990s, there was a guy in my cohort group who said he could ‘talk to people on his computer.’ We thought he was totally weird and even a bit nuts. He was what we called a computer geek. In reality, he was an early adopter of what we now know as email … something that to a doctoral student in a communication program seemed like science fiction.

“Cellphones were unheard of. The World Wide Web was just coming on the scene. The computers we did use took up the better part of our big old metal desks and were only used to do word processing. To do our statistical analyses,” Bruess recalled, “we had to go to the big building next door where they housed the mainframe computer, and wait in line to pick up our dot matrix printing ... which would come off a machine the size of a small, two-engine plane.”

Much has changed in the past quarter century. “Today, many couples and families have found that tools such as Facebook, SnapChat, texting and FaceTime have brought them closer and made their relationships feel stronger, especially when people live in different cities, states or countries,” Bruess said. “On the flip side, when people in family relationships turn to digital technologies to distract them or use them in negative ways, such as not allowing their college-age kids appropriate independence or allowing phones and texts to get in the way of conversations, they can hurt relationships."

Bruess said that the most surprising finding in the book is “probably that marriage and family therapists have begun recognizing that when working with families and couples in clinical settings, the digital devices – the phones and iPads – need to be considered another 'family member.' Our devices and our attraction to digital technologies can be that strong. No question, that's a bit disturbing and eye-opening. Many people, probably too many people, are very 'in love' with their technology. Therapists are seeing it too often in their offices. That, no doubt, was a reality-check moment."

Bruess co-wrote the book’s sixth chapter, “Facebook Family Rituals,” with a former St. Thomas student, Tammi Polingo, who now is in the Master of Social Work Program at the University of Chicago, and Dr. Xiaohui Li, a professor of family social science at Northern Illinois University. Their research found that family members who use Facebook with other family members tend to be happier and feel closer to their families than those who don't.

“We found that families are using Facebook as a digital-age ritual of connection. They use Facebook to let others in their family know they're thinking of them, share updates on daily mundane events, send positive messages of support and keep each other updated on life."

This, Bruess said, is kind of like the way dinner rituals used to function for many families.

“Others said they used Facebook as a venue for playing or having fun with family members both near and far, similar to the way they would joke and poke fun of each other when together. Other authors in the book reported that family members – especially those living far away – developed new rituals to keep them feeling close, especially grandparents who liked using Skype to read to their grandchildren before bed, or parents who were gone for long periods of time would do the same,” she said.

And while we are now seeing websites devoted to weddings, or “wedsites,” Bruess does not think we’ll ever replace the actual, important big events and rituals of our lives with online versions of those events.

“As humans, we still do want to be together physically during big life transitions. Rather, I do believe – as the onslaught of wedsites reveals – that we no longer are solely constructing the meaning of events during and in the actual moments of those events.

“As humans, we still do want to be together physically during big life transitions. Rather, I do believe – as the onslaught of wedsites reveals – that we no longer are solely constructing the meaning of events during and in the actual moments of those events.

“As we become more online in so many aspects of daily living, many of us are enhancing and extending the experience of big life transitions by documenting them online, inviting others to participate in them before, during and much after they actually occur, by engaging our family and friends in digital sharing, communicating, anticipating and even reminiscing after the event,” she said.

One of the book’s contributors observes that today’s adolescents are “digital natives” but their parents are, for the most part, “digital immigrants.” So, are the adolescents of today fundamentally different today than before the advent of social media?

“One of the burning questions many of us who study humans in the digital age have – and argue about – is whether we are fundamentally changing as humans as a result of our intense relationships with and use of digital technologies. Or are those technologies really just tools like anything else we humans have adopted and adapted to over the millennia ... flints, axes, hammers, machines, paper, printing press, etc.,” she said.

“Some scientists who study the digital age brain argue we are, indeed, changing at the core: the way we think, the way we interact, the way we feel, and even our capacity to love and show empathy. I want to believe that the tools in front of us are just that: tools. And that we have to make smart choices about how we use those tools. Just like any tool, we can use them for good or for ill.

"That's what I want to believe, but I'd be lying if I said I'm not worried about our collective obsession with these mini-computers we carry around in our pockets. Our smartphones have become our go-tos for nearly everything in our daily lives, and that gives me pause about the future of humans and their ability to have deep conversations – something we know is, unequivocally, the foundation of great relationships," she said.

Bruess, on the St. Thomas faculty for 18 years, also is author the 2005 Contemporary Issues in Interpersonal Communication (with Mark Orde), the 2008 What Happy Couples Do, the 2009 What Happy Parents Do, the 2010 What Happy Women Do (with Anna Kudak) and the forthcoming The Happy Couple: How to Become One (Again).

She and her husband, Brian, live in St. Paul; they have a son, Tony, at Stanford University, a daughter, Gracie, at Cretin-Derham Hall High School, and a little dog, Fred.