During graduate school, as I studied religious responses to the great plague of 1347, I could not help but notice parallels to the HIV/AIDS pandemic of our own day. Just as in the Middle Ages it was believed plague came as a punishment from God for sinful deeds, so did we hear some preaching that AIDS was God’s punishment unleashed on a sinful humankind. Just as those falling ill with fevers were ostracized from the community in medieval Europe, so were those acquiring opportunistic infections shunned from many communities in the United States, Europe, Africa and Asia. And just as some – just a few, really – responded courageously in the Middle Ages, providing relief when the stress of illness seemed to overcome all else, so did few at first, but more over time, offer friends and loved ones assistance as AIDS shut down immune systems, killing one, then one thousand, then one million.

Noticing these parallels, and watching the numbers of people who have died from contracting this virus climb now to more than 33 million, it was only a matter of time before I became actively involved in HIV/AIDS response. For much of the past decade, I have been immersed in an interdisciplinary study of theology as it pertains to public health, humanitarian engagement and documentary photography. This has led, finally, to the photographs and scholarly essays that, together, comprise “30 Years/30 Lives.”

In 2011, the world community marks the 30th year since the Center for Disease Control and Prevention announced that a new virus had entered the human population. To commemorate this significant year, I traveled while on sabbatical during academic year 2009-2010 to South Africa, Thailand and Mexico. In these countries, as well as my own, I collected stories and photographs from people who wanted to share with me their perspectives about the illness and its impact.

The resulting photographic exhibit provides testimony from those who are experiencing the pandemic firsthand, whether directly by an infection, or indirectly through loss or care for a loved one, or through engagement in humanitarian response. Not all of the participants are HIV-positive, but each one recognizes how the world has not been the same since this virus arrived in the human family 30 years ago.

I met each participant by contacting an organization that was responding to one of the structural drivers of the pandemic. These non-profit organizations and NGOs are addressing issues such as poverty and hunger, religious fundamentalism, xenophobia, inequitable access to health care, violence against women, political violence, mistreatment of vulnerable people (elders and orphans), AIDS denialism, human trafficking and inequitable access to education. After thoroughly introducing my project and the ethical principles I would follow, I asked administrators from each organization if they would be willing to participate by inviting three people affiliated with their programs to share their stories by writing into a common journal, and then by sitting for a portrait.

For this issue of CAS Spotlight, I am sharing the photographs and stories from three of the participants from South Africa: a boy in Guguletu who never expected to see his seventh birthday; a man in Samarra who went blind due to an opportunistic infection and who fears for his daughter’s safety; and an elder from a community outside of Cape Town who is caring for her daughter and her daughter’s children. In different ways, I continued to be in relationship with all three of these individuals and their families even once the project was finished.

“30 Years/30 Lives” grows out of a conviction that the basic problem with how the public reacted to the pandemic initially, and continues to respond in many ways, is fundamentally a problem of vision. By peering at the pandemic’s victims as expendable, many in the human community displayed a troubling lack of insight. Some, however, demonstrated an alternative way of seeing. Where others only saw deformity, some recognized the inherent worth of people living with HIV. Where others saw a lacking of dignity, some noticed the value that is inherent in every human life. Where others observed nothingness, some responded with compassion to the diminished and vulnerable state of another.

“30 Years/30 Lives” invites viewers to look, trusting that the real presence of Beauty – a name for God in the Christian tradition – in these images will capture our gaze, transform us to envision the world anew, and empower us to breathe a more equitable and peaceful common existence into being.

To learn more about “30 Years/30 Lives,” visit the project’s website at https://30years30lives.org.

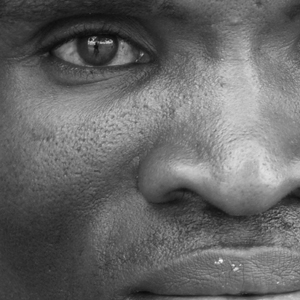

“Participant 05” is a 7-year-old boy who struggles with meningitis, among other opportunistic infections. His mother writes about their challenges in her journal entry.J. L. Zwane Community Center, Guguletu, South Africa, 2009

In 1992, after being involved in a car accident, I was diagnosed HIV-positive. I knew very little about HIV and I had no sign of being ill or of the struggle that la[id] ahead for me and my family. I was healthy and fit until 2001, after I had fallen pregnant with my youngest son. I had two children already, so I thought it was no big deal. After a difficult pregnancy, I gave birth to a baby boy, [who] was immediately diagnosed as HIV-positive. His CD4 count was zero, like myself, and the doctors predicted a very short life span for him, for he had TB at birth. Today I thank God, for he has celebrated his seventh birthday in July this year. In spite of being a very sick boy, he also goes to school when he can, and when you look at him some days, he looks and plays with other children like any 7-year-old. I try to make his life as normal as I can, for in a house with lots of grandchildren and friends, he is the only one who is very sickly and sometimes does not go to school for long periods at a time, and misses a lot of school work, but he at least gets some kind of education. He has been put on the second line of ARVs, because of his very high viral load and very low CD4 count. At the moment, he is suffering from slow meningitis, and I am suffering from cancer and four other opportunistic diseases. Through all our past and future struggles, I thank God for the strong support system I have at my church and support group that I joined about four years ago. They are with me every step of the way and it makes my life a whole lot better than it could have been. I am also an HIV and AIDS activist, for I know that HIV [and AIDS] are maintainable, if you take your [medicine], and abstain from sex or protect yourself, and surround yourself with family and friends as a strong support system. Aluta continua! (The struggle continues.)

“Participant 19” cares for an HIV-positive daughter and her children, sharing openly their struggles with alcohol and drug addiction.Ikamva Labantu, Cape Town, South Africa, 2009

I am a 67-year-old mother of two. [My] daughter is 44 and son is 42. In 1994 my first-born daughter was diagnosed HIV-positive. She grew up in the Eastern Cape [and was] brought up by my mother. At first I blamed myself [for] not bringing her up myself. But later I accompanied her to the clinic for counseling. It took time for her to accept [her status]. She kept saying it can’t be her blood. I kept taking her to different places to be tested. At last she believed it and kept it [a] secret at home. I tried to go to workshops to learn more about this disease. It is very difficult to live with my child. She turned to drinking and gets very aggressive when drunk, which is almost every day. She has two sons. I brought them up myself and put them through education. They are both working but [are] affected by the situation. The younger one is on drugs. They all stay with me. I am only sane by the grace of God. We pray together most of the time. I support them with my pension. I struggle to have [her take her treatments]. It is a miracle she lasted so long taking medication and alcohol. I praise the Lord for all blessings. I[t] affects me [for] whenever she is in pain she comes to me and I can feel the pain. The big blow was this year when I phoned a place she went to for chest X-rays. I was told she has no lungs. I nearly died. All in all, it is not easy to nurse someone who sometimes blames me for wanting her to die. I pay for funeral policies. She doesn’t get [a] disability grant because she drinks. It is depressing. I just trust in the Lord to make me strong when the time comes.

“Participant 11” describes his situation in Samara, a section of Philippi, where access to food and water are scarce. He is especially concerned about the safety of his daughter.Inzame Zabantu Community Health Center, Philippi (Brown’s Farm), South Africa, 2009

I am from the Eastern Cape. I’ve been here for four years now; I came to Cape Town in 2005 looking for work. I was employed, and was on treatment in 2005. And I was married. But she was very sick – vomiting, with diarrhea. Her entire body was aching. She was unable to walk. She was not on medication; she did not go to the clinic to see what the problem was. Instead, we went to our church to ask the pastors to pray for her to be healed. But she passed away earlier this year – in June. We have a daughter who will be 13 years old this year (grade 6). She is staying with me. We are alone now. This is the second month I have been unemployed because of poor health. I was losing my eyesight; I have gone completely blind now. Also, I had terrible pains on the right side of my chest. I went to the doctor to see if it was TB. I am still waiting for the results. I am underweight. We have very little food to eat and no money. We are staying here in a very poor community. We live in a shack. More than 15,000 people share one tap of water here. Four families share every toilet. The situation is very difficult. The government distributes porridge to try to avoid a famine. When they are able, our neighbors sometimes give us their leftovers. Because I am HIV-positive, I may qualify for a grant to help subsidize us. We are waiting for the CD4 count to come back to know whether I qualify. But it is taking so long. It is terrible for my daughter. She goes to school hungry. I am worried about her. I’m worried she will be abused – that when I’m gone, people will offer her bread to sleep with her. We have no one to look after us. Can anyone help us? Please, can anyone help us?

Read more from CAS Spotlight