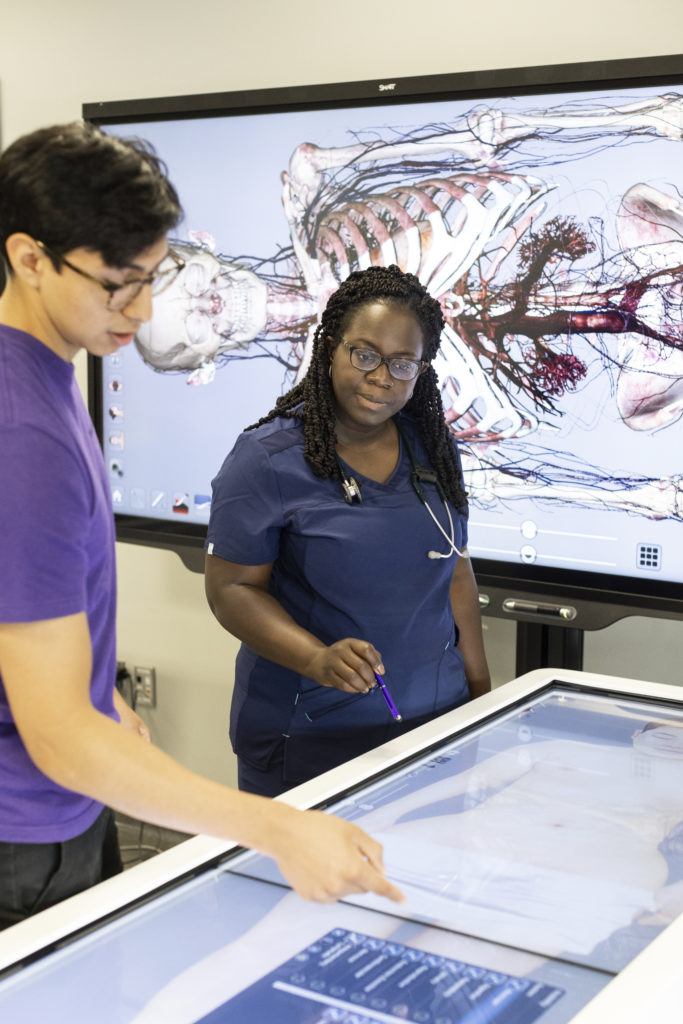

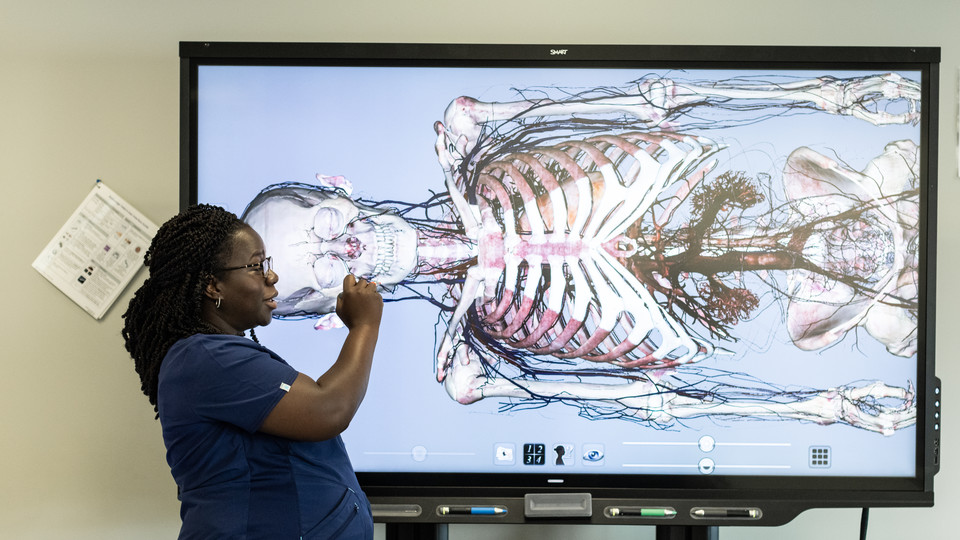

Giving birth to her own child is what reinforced for Berline Pierre-Louis, a clinical faculty member in the St. Thomas School of Nursing, just what an impact a good nurse can have on society. Her hospital stay gave her a close-up view to the other side of patient-provider relations than the one she experienced through her years as a nurse.

Good care includes the “little things,” she said, from asking patients if they need a water refill, another blanket, or simply acknowledging the other people in the room. Regarding nurses during her own hospital stay, which lasted 10 days longer than expected, she said, “Some people would just walk in and completely ignore my husband. How do you walk into a room and not say hi to everyone in that room? Culturally, where I’m from, it's just rude.”

Although she’s from the Twin Cities, she arrived in St. Paul at the age of one, when her parents immigrated with her from Haiti. Her approach to patient care is rooted in an appreciation for caretaking by her mom, aunts, and grandmother.

“I think there's a lot of knowledge to be gained from the moms and the grandmas of the world about how you just take care of people and make them feel better,” she said. “It's like heating up water or making hot tea or just sitting with someone a little bit longer.”

Culture Can Make a Difference

As a patient, Pierre-Louis saw an average of three nurses every day and noticed there were very few nurses of color and few who understood the immigrant population. She noted that the healthcare system could be “less than ideal or traumatic” for such people. For example, some doctors or nurses often assumed that her mother did not understand English because of her accent.

Pierre-Louis’ experience as a patient made her think about how culturally responsive training of nurses can translate to making patients feel more comfortable.

She observed her situation from the unique vantage point of being Black, as well as being a healthcare provider and an educator.

As a provider, she knew the data behind the work. Black women face worse outcomes in maternal mortality and infant death relative to white women, with over triple the number of pregnancy-related deaths per 100,000 live births, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Research shows that implicit bias and structural racism within the U.S. healthcare system is exacerbated by a lack of diversity in nursing, Pierre-Louis said. In January 2020, the Minnesota Department of Health reported that only 9% of all actively licensed registered nurses in Minnesota identify as a person of color despite being approximately 20% of the state’s population, and growing. The report notes the vast majority of RNs also only speak English in their practice.

Pierre-Louis sees these disparities in health outcomes arise as a function of not prioritizing public health or cultural competency in nursing programs.

“Most of your time and training as a [nursing] student is spent in acute care, so big hospitals or long-term care facilities, and those are generally high stakes environments,” she said. “But what I've come to understand in my different roles outside of acute care, is there's this whole other element of understanding people's lived experience that is sometimes missing.”

Healthcare is often fast-paced and high-pressure, preventing providers from fully understanding what is happening with patients, she said. In turn, patients might get pegged as “troublemakers” or “noncompliant” when other factors related to following doctor’s orders might be at play, such as lack of financial resources, language barriers or homelessness.

Now, through teaching at St. Thomas’ School of Nursing, Pierre-Louis plans to use her real-world practice and experiences to equip future nurses to care for all kinds of people.

Journey into Nursing

“Berline has a passion for increasing nursing workforce diversity and strives to create curriculum and instruction that is culturally responsive, which will have a great and positive impact on our students,” said Dr, Martha Scheckel, founding director of the School of Nursing, a division of the Morrison Family College of Health.

Neither nursing nor nursing education were a part of Pierre-Louis’ initial career goal even though her sisters are also nurses.

“I thought I was going to major in biology [as an undergrad],” Pierre-Louis said. She was drawn to science and caring for others and, realizing that nursing is an in-demand career, she decided to go for it.

While Pierre-Louis attended college, a research opportunity in public health sparked her interest, but post-college, she started her career in community mental health.

Pierre-Louis still had public health on her mind when she began working in direct care in neuroscience at Regions Hospital. “I was seeing patients with a lot of acute issues brought on often by chronic health problems and I thought, long term, where do I see myself making the most impact?”

She eventually pursued a Master of Public Health from the University of Minnesota, with a specialization in policy administration in order to understand how policy at all levels can affect health.

Following graduation in 2014, she worked for Park Nicollet in population health, looking at how to help a group of patients, based on demographics, have better outcomes. She landed work for Ramsey County Public Health, and most recently was at Allina Health-United Hospital, where she started in infection prevention right as COVID-19 was taking hold.

When the opportunity to teach at St. Thomas knocked on her door, Pierre-Louis jumped on the chance to have a greater impact for underrepresented communities. The nursing school aims to enroll at least 30% students of color and students from other underrepresented backgrounds.

“I felt like what was happening at St. Thomas in building this program was really well aligned with my personal values, and also aligned really well with my public health experiences,” she said. “With where we are in the country with our healthcare system, the way that healthcare is delivered, and many of the things that have transpired in the past couple of years around racism and police brutality, I think we have a duty to educate and train nurses who are equipped to take care of people who are living in this reality. And I'm hopeful that we’re educating people who will be change makers.”

Mark Brown / University of St. Thomas

Mark Brown / University of St. Thomas