A recent piece in The New York Times noted that total health insurance premiums doubled between 2003 and 2010 and that the portion of premiums employees paid increased by 63 percent. The trend seems to be toward eliminating employer-paid health insurance. What impact does this have on recruitment, retention and overall employee job satisfaction?

To answer this question, I first need to set out a context and two caveats. The context is that above a certain income or wealth level – a relatively modest one for most of us reading this – people consider a broad bundle of elements in their decisions to go to and stay at an employer, and a related bundle of factors affect our ability to be fully engaged at work and to perform highly. Health care benefits and the proportion covered by the employer are important elements in these bundles, but not the only ones, or even the primary ones for most employees.

The caveats to this general answer are that for the working poor, conditions are desperate, and that for all of us, this answer may change in the future. Health care is more uniform and nationalized in most developed countries than it is in the United States, where our cultural values tend toward a very high level of independence and a reliance on markets to regulate. If nothing changes on that front, and if health care costs continue to rise dramatically, employer offerings of and payment for health insurance could become a more important, direct element in employers’ recruiting and retention tool kits.

Generally, however, we consider health and well-being factors more broadly in our decisions about our jobs.  I recently started the University of St. Thomas Work and Well-Being Study (UST-WWS) with second-year UST MBA students Sara Christenson and Annelise Larson to explore just such issues.

I recently started the University of St. Thomas Work and Well-Being Study (UST-WWS) with second-year UST MBA students Sara Christenson and Annelise Larson to explore just such issues.

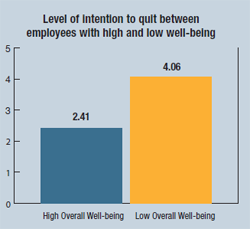

Working with a local organization, we found that employees’ overall holistic sense of well-being may be a greater predictor of retention than any jobspecific factor (see chart; scale is for efforts to leave the organization where 5 = monthly and 1 = never).

Overall well-being consists of a bundle of domain well-beings, such as career, financial, social, leisure, health and community well-being. In our initial UST-WWS sample, financial well-being was one of two specific domain well-being measures that related strongly to retention and presenteeism at work (“presenteeism” is a term used to capture the notion that people are physically at work but unable to be fully engaged and productive).

And this is how I come to my answer to this question: It is through the overall financial well-being of America’s workers and their families that the impact of health care costs will most significantly be felt. If, as has been the case for over a decade, discretionary incomes continue to fall because the relative costs of essentials such as food and health care rise dramatically, the financial wellbeing of Americans will continue to fall, affecting our ability to create full, stable lives that include staying with the employing organizations that best fit our interests and talents. As basic living eats up a greater proportion of our paychecks, affecting our overall financial well-being, UST-WWS findings suggest that this will impact our overall well-being and our ability to be fully present, engaged and productive at work.

Teresa Rothausen-Vange, Ph.D., is professor of management and holder of the Susan E. Heckler Endowed Chair in Business Administration in the Opus College of Business. You can reach her directly at tjrothausen@stthomas.edu or (651) 962-4264.

Read more from B. Magazine