During the height of the recent global recession, one country stood out as the only one to avoid recession – China. At a time when the United States saw its gross domestic product decline by more than nine percent, China’s GDP declined by less than 2 percent. As the United States was increasing its deficit by $1.4 trillion, China increased its economy by 10 percent and added $500 billion to its reserves. While cities in the United States have struggled to fund necessary repairs or additions to their infrastructure, China has spent the last decade building its own high-speed railway. And, whether we like to admit it or not, the fact that China avoided a recession kept the rest of the world’s economy from hitting bottom. How has it achieved such economic success and become, for the first time in recent history, a real player in the world market? It had a plan.

The Chinese Reformation

Leaders of the Communist Party of China, coming to power in the late 1940s, wanted to change the nation into a modern socialist state. To do this, they had to focus on industrializing, improving living conditions and producing a stronger military. But the leadership struggled to balance its economic goals with its socialist goals – goals which often seemed in direct opposition to each other. In 1978, party leaders introduced a program of economic reform, having decided that central control of the economy as envisioned by the Maoists had failed and led China to fall behind not only the West but also to close neighbors and new economic powerhouses such as Singapore, Taiwan and Hong Kong.

At the time, the average Chinese family was faced with the rationing of food, clothing and basic household necessities. The reforms were designed to increase broad access to the marketplace, expand investment opportunities and reduce central control. The first private businesses in China were family-owned and were not permitted to hire non-family members. One of the first of these entrepreneurial enterprises was Ping An Insurance.

Initially, the company sold life insurance from bicycles. Today, it employs more than 400,000 people, trains each of its employees at Ping An School of Financial Services (complete with an 1,800-room hotel) and has assets of $935 billion. In 1994, it began accepting outside investments from the likes of Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley. Why did the company succeed? Because, historically, the Chinese have been risk takers. With nothing to lose, they had everything to gain.

Today, China has the second largest economy in the world, taking over that spot from Japan in late August 2010.

Throughout the 1980s, the Chinese leadership continued to allow natural businesses to develop. Today, China has the second largest economy in the world, taking over that spot from Japan in late August 2010. In the last five years, it has passed the United Kingdom, Germany and France. If this pattern continues, it will surpass the United States in the next 20 years as the largest economy in the world.

China avoided recessions due to the simple fact that the Chinese government maintains control over the economy while allowing – to a certain extent – a free and open economy. This is a hard concept for Americans to understand because we’ve been raised on the idea that socialism and capitalism are polar opposites. Capitalism in the traditional definition permits anyone to create and expand any enterprise. The market decides whether that enterprise succeeds or fails. Lose money in an investment? Too bad – you should have done better research. In a purely capitalist society, the government doesn’t protect people from making bad decisions or even force them to share the wealth. A capitalist government doesn’t control the economy.

In a purely socialist environment, the government is the agent that transfers the wealth from one individual to another. The government controls industry, investments and any wealth created as a result.

In truth, however, there is no pure socialist or pure capitalist society. History has demonstrated that pure socialist states – Cuba or the U.S.S.R., for example – generate a declining economy that implodes after a period of time.

I once gave a lecture at an electronics company in Russia. The central government planning agency developed a five-year plan and created factories, production centers or academies that were responsible for making one thing for the entire country. I visited a place in the middle of Siberia that made televisions for the entire U.S.S.R. The factory employed about 45,000 workers. It had been trying to convert the factory to better compete on a global scale, but the goods it manufactured were poor-quality and outdated, so it couldn’t export. I tried to deliver a lecture on capital formation, but the questions kept coming back to human resources – how to motivate people to work when they not only did not care about the product they were making but had no share in the financial outcome of the product’s success – or no financial penalty if the product failed.

China has, since the late 1970s, taken a different approach. In this system, the government has control over the economy but doesn’t dictate – unless it feels it is necessary – which economic developments will occur. For example, China, too, experienced a housing bubble; rather than letting the market dictate the outcome, the government stepped in. In January 2010, it told banks to loan less than they had previously. In February, the government dictated banks decrease loans yet again. By March, banks were further restricted in making housing loans at all. If the United States had done the same, we may have seen fewer foreclosures or banks in crisis. Yet this government intervention is anathema to traditional free-market capitalism.

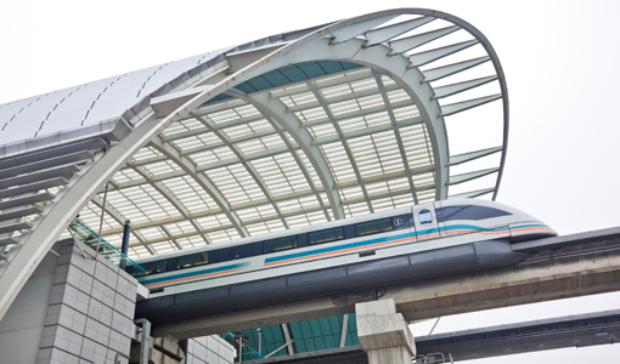

Another factor influencing China’s ability to avoid a recession is its stimulus program.When the government realized Western nations would halt imports to shore up their own economies, China developed a stimulus program to create consumption within the country. Just as the United States “cash for clunkers” program gave American car-buyers incentives to purchase new cars, Chinese consumers were given incentives to buy consumer goods. Shopping chits were issued for the purchase of televisions, washing machines or vehicles for a limited time, ensuring that production remained stable even though exports to Western countries declined. In the U.S. dollar equivalent, the stimulus was worth $5 to 6 trillion. The government also infused close to a trillion dollars into building infrastructure rather than manufacturing goods for export. China had planned to build thousands of miles of railroads over a 10-year period. With the stimulus, those railroads will be completed in two years. So they buoyed their own economy, which in turn benefited commodities such as oil and coal, which transferred a benefit to other countries in Asia and even in Australia.

A New Model of Capitalism

The People’s Republic of China includes the mainland as well as Hong Kong (since 1997) and Macau (since 1999). We know The Republic of China as Taiwan and it, regardless of who “owns” the country, is part of the regional China economy. The Chinese government continues to look to Hong Kong, Korea and Taiwan as places not just to obtain financing but to acquire the knowledge and skill sets necessary to set up and operate new businesses, especially in the service sector. Hong Kong serves as the banking arm of the China region. It has an advantage not only in providing services but in understanding how to attract and manage trade from a variety of non-Asian countries. China’s goal is to make Shanghai the economic center of China, and the government is using Hong Kong as its model.

While the People’s Republic of China was struggling under early Communist socialization efforts, the Republic of China, or Taiwan, was attempting to enter the global market, first with land reforms in the 1950s, then with government planning and an emphasis on universal education. Also, Taiwan was a beneficiary of foreign aid through the 1970s, allowing it to move to an industrialized nation and establish critical economic links. It has now gone from being the home of cheap textile and toy manufacturing to a developer and manufacturer of electronics and other advanced technology. China hopes to learn from Taiwan’s transformation and success.

A good example of the importance and growth of Taiwan is its GDP. The U.S. GDP per capita is $46,000. In Taiwan, it’s $32,000. That doesn’t sound like much, but it places Taiwan 43rd in the world. The U.S. GDP per capita ranks 11th in the world.

China’s GDP per capita is generally presented in “normalized” terms. One issue at stake with the country is that its currency is artificially depressed by about 30 percent (by the government) to ensure that Chinese products are less expensive to the rest of the world. So while the stated per capita GDP is $6,600 (128th in the world), most economists and financial experts put it closer to $9,000.

In Western nations, we have an image of China as a poor, developing country. But there are really two Chinas. On any given day, mainland China is home to 500 million people who are considered middle or upper class – more than the entire U.S. population. These people have good health care, are educated and either own their own businesses or are well-paid managers and executives. This population is concentrated on the east coast of mainland China in very large cities.

There are 800 million people in the “other” China who live a very poor life. The government provides them with food, so they do not generally go hungry, but there is little industry or education and almost no opportunity for entrepreneurship or growth.

To correct this imbalance, the Chinese leadership embarked on an initiative 20 years ago to move 20 to 30 million people each year from rural to urban areas. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development has posited that, in order to be efficient, a nation needs to urbanize 70 percent of its population. Today, China is approximately 35 percent urbanized. Twenty years ago, when they began the controlled immigration, that figure was in the teens. But in order to accomplish the necessary 1 to 2 percent annual population transition, China needs an accompanying economic growth.

Under this model, if a company wishes to build a new factory, the government dictates where it can build and from where it can recruit new workers. Laborers from rural areas then move into dormitories for their tenure at the factory. This is how the country has built up cities such as Shenzhen and Shanghai, and how the next large urban centers will develop. For example, the government chose Wuhan as the hub of China’s high-speed rail. In the next 15 years, as high-speed rail is expanded across the country (and to other countries), Wuhan will grow from five to 30 million people.

Unlike past leaders of the PRC, the current government is interested in developing the country to be urbanized and even westernized. They don’t, however, want to cede control of the overarching plan. And the only way to maintain this control is by orchestrating growth and centralizing authority.

From a U.S. perspective, this smacks of socialism and over-regulation. But some may argue that the United State is more socialized in some respects than China. We have a Social Security Administration designed to provide a safety net for Americans after they retire. If you earn an income more than $30,000 per year, your benefits decrease as your contributions increase. This is, in essence, a wealth sharing system. In the last two years, the U.S. government has taken control of large private enterprises in order to protect the economy. So if we were to point to one country as socialist and one as capitalist at this time in history, to whom would we point? China has developed a new economic model, one which seems to be succeeding.

What the Future Holds

The future economic success and progress for China lies in infrastructure and financial services. This is where most business development is occurring. Consumer products and transportation also are key: In 1990, 1,000 cars were sold in China. Last year, that figure reached 18 million. That figure would have to reach 60 million per year to have the same impact as it does in the United States.

But China’s progress also is dependent on its ability to resolve some very real and very contentious issues, among them taxes, the valuation of its currency, Taiwan and human rights.

While taxes in China are not as high as in other developed nations, there is a penalty on non-Chinese-owned businesses. The impetus behind this policy is to nurture Chinese companies. But failure to ameliorate the impact of high taxes may drive away some businesses in the coming decades.

The undervalued Yuan also is a potential roadblock. China will need to revalue its currency to proper valuation, which means a 30 to 40 percent increase in the dollar relative to the Yuan, which makes Chinese products 30 to 40 percent more expensive and U.S. products 30 to 40 percent less expensive in China. If they don’t do this, they will have inflation. The government began this process in 2005 and 2006, halted it when the global recession hit and has recommended devaluation on a smaller scale.

The ongoing conflict over Taiwan also will need to be addressed. This is influenced, in part, by the Communist Party’s ability to maintain its current level of control. The party is two million strong in China. Yet they decide the fate of 1.3 billion people. China is clearly not a democracy, but as long as there is economic progress and growth, the Chinese people may be tolerant of the status quo. Eventually, however, the government will have to give the people more governmental influence and control. This is another instance where the People’s Republic of China may wish to look to the Republic of China for guidance. Chiang Kai-shek’s successor, his son Chiang Ching-kuo, selected Lee Teng-hui to be his vice president. After Chiang Ching-kuo died in 1988, President Lee Teng-hui became the first ethnically Taiwanese president of the ROC and, following his democratization efforts, became the first Taiwanese president to be elected by popular vote.

Perhaps the greatest obstacle to China’s continued development is its human rights record. The Chinese government historically has limited freedoms of speech, movement and religion. Policies such as capital punishment, the one-child policy, limitations on legal and labor rights all contribute to external perceptions of the nation and its people. At this time in history, however, there is no denying that China, in all its complexity, is much more than an emerging force. In all aspects that make a difference in a global economy, China has emerged.

Read more from B. Magazine