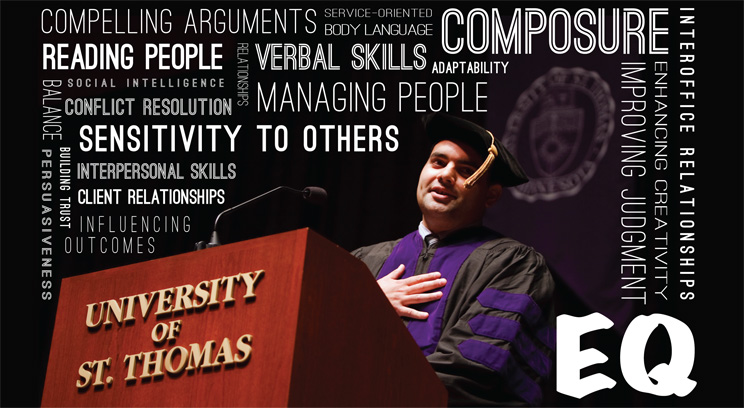

What separates great lawyers from good lawyers? You can read about their accomplishments, but how do you know if you want to work with them? You have to meet them and see if they are the right match. How that person behaves or fits in depends on his or her social intelligence, sometimes called EQ (emotional quotient). People are more familiar with IQ (which measures intellect) but EQ can make or break the success of a lawyer.

“For example, strong analytical thinkers must find a way to transfer ideas and conclusions so they are well received and understood. Without EQ, the delivery of ideas and conclusions can create defensive barriers that block the transfer of innovative, creative and well-reasoned legal ideas,” said Lisa Brabbit, senior assistant dean for external relations and programs at the School of Law, who is a firm believer in the importance of EQ. “In a sense, EQ becomes the conduit for IQ to flourish.”

The significance of IQ is not devalued at the School of Law, but in a client-service profession such as law, the value of EQ is paramount.

“One of the debates about law schools is whether they’re ‘merely trade schools’ or academic schools,” said Joel Nichols, associate dean for academic affairs and professor at the School of Law. “The choice is supposed to be teaching students the hands-on tasks versus teaching only the theory of the law. At St. Thomas, we have never embraced either model; rather, we’re intentionally focusing on the lawyer as a whole person and what it means to serve clients – and that will necessarily include both the skills and the theory also.”

The School of Law knows that to educate the whole person, in addition to academics and skill building, it must help students develop their EQ.

“Law is a service profession,” Brabbit said. “At its core, it’s dealing with people and relationships. In a social situation, you can’t IQ your way around it,” she said. “One of the key things that allows our alumni to succeed is EQ. If employers don’t include EQ as a hiring factor, something suffers, either culture, employers, clients or all of these.”

Importance of EQ in the Legal Profession

Relationships are the foundation of law. As attorneys interact with clients, colleagues and judges, they need to resolve conflicts and build trust. Lawyers need to know how to read people so they can respond to the needs of their clients effectively, whether those clients may be nervous, angry or emotional. When arguing in front of a judge they must keep their cool and facilitate rapport. These interpersonal dynamics influence the outcome of both social interactions and legal matters.

“Relationship skills and intuition skills are critical for great lawyers,” Nichols said.

The School of Law prepares its students to be relationally focused. “We help them learn how to raise the right questions and establish the best relationship with a client. You’re going to make a mistake at some point, but if you have a relationship built up, you’re more likely to be given grace, and that builds trust over time,” he added.

Relationship skills are enhanced by a person’s EQ. Kendra Brodin, director of the School of Law’s Career and Professional Development (CPD), noted that if a student’s EQ is high, they’ll do well in an interview. The CPD staff conducts mock interviews to teach students where they are not showing their EQ and should. “Employers want to hire someone they want to work with and someone who will make a good impression on their clients,” she said. “It’s about more than grades and experience; it’s about fit.”

Ruth Dapper ’12, is a judicial clerk for Judge John P. Smith and former clerk for Judge Wilhelmina Wright at the Minnesota Court of Appeals. She credits the School of Law for helping to develop her technical proficiency as well as her interpersonal skills. “Inherent in professional development is the nurturing of emotional intelligence, such as the ability to relate to and work alongside others during times of high stress as well as pleasure,” she said. “The staff and faculty of the law school continue to help me maneuver through professional situations that require perceptiveness and sensitivity, such as seeking or declining an employment offer, networking, and respectfully serving an employer while also providing her with honest insight into a muddled legal question.”

Martha Capper, a recruiter for Robins, Kaplan, Miller and Ciresi L.L.P., talked about the importance of relationship skills and EQ for the associates it hires.

“Once someone builds strong legal skills, they need to go outside the walls of law firms and put other skills to work to benefit themselves and the law firm,” she said. “In a private law firm, attorneys are establishing their credibility and asking for business.”

Capper explained, “As you move up the ladder in a private firm, you’re developing legal skills the first few years – the ability to analyze problems, take depositions, argue motions and present to clients. After lawyers have proven this foundation they’re asked to do more in a firm: manage people and manage projects. If you can’t manage a team, you won’t end up with a good outcome. How do you incentivize people? How do you motivate them?” These are EQ skills.

Several years ago Robins, Kaplan, Miller and Ciresi looked at its most successful lawyers and decided to hire people with the characteristics they shared. It developed a behavioral interviewing strategy around these traits and used them to develop a set of 17 competencies that its associates need in order to move up in the firm, and it has four tiers of advancement.

For example, here are seven competencies it requires for junior associates to assure their long-term success:

- They must be problem-solvers.

- They need a strong work ethic.

- They require drive and resilience. “We want someone who wants to be successful,” Capper said.

- They must have strong writing skills relative to their peers and continued improvement in their writing abilities.

- They should possess the potential to develop into leaders.

- They must be analytical thinkers.

- They must be relationship builders.

Capper points out that the competency of “relationship builder” actually permeates all of the other competencies.

“The best lawyers with the happiest clients are other-centered rather than self-centered,” Nichols said. “We’re intentionally teaching our students to move down that path – to know what clients need and deserve. It also helps them in their standing and stature in the community and in their job satisfaction.”

“Working in a law firm is different from school in that you need to draw on much more than what you learned sitting in a class,” Capper said.

One of the best ways to learn EQ skills is using them. The School of Law has been very intentional about building experiential learning inside and outside the classroom.

Brabbit explained, “EQ is fine-tuned when we understand that the mother-board of the profession is an intricate, detailed and fragile network of human interaction. And the delivery of legal services, the stewardship of intellectual skills, the ability to find and maximize passion for a vocation in law, even self-confidence and self-perceptions, are all tied to the ability to engage and grow professional relationships. For students, investing time engaging and growing professional relationships, in addition to the benefits of the classroom, will not only help to close a number of gaps between legal education and the profession but also it will make them better professionals in the long run.”

In practicum courses, students deal with simulated clients. For example, in Professor Teresa Collett’s course, Constitutional Litigation, teams of two students initiate a case challenging the constitutionality of a law and defend a different law in a case initiated by their classmates. Students prepare all pleadings in both cases, engage in limited discovery including the preparation and deposition of expert witnesses, and conclude with arguing motions for summary judgment.

“In my Contracts class,” Nichols said, “we stress that you have to understand the business of your clients before you can help them make decisions. You have to understand their culture and how their systems work. Will their highest goal be to maintain their business contacts in the community? Is litigation the best way to go?”

Verbal and nonverbal skills are emphasized in courses such as Lawyering Skills, Client Interviewing and Counseling, Negotiations, Mediation, and Alternative Dispute Resolution.

Outside the classroom, students have many opportunities for experiential learning.

Through the Interprofessional Center for Counseling and Legal Services at the University of St. Thomas, law students collaborate with faculty, staff and other students from law, psychology and social work to meet the needs of clients with complex legal, psychological and social issues.

Under the guidance of the center’s faculty and fellows, law students represent and assist underserved populations of the Twin Cities in 10 practice areas: elder law, immigration law, community justice, consumer bankruptcy, bankruptcy litigation, federal commutations, appellate, appellate immigration, misdemeanor defense and nonprofit organizations. Student connection to clients is deep, and the work is often intense.

With extensive client interaction, the center provides opportunities for experiential learning. With supervision, students work on real cases, performing client intake, completing and filing motions and briefs, and more.

More Community Connections

All School of Law students are required to participate in the Mentor Externship program. The school was rated No. 1 in the most externship placements per student in recent National Jurist surveys.

The School of Law has forged a lasting partnership with the lawyers and judges of the Twin Cities legal community who volunteer their time to serve as mentors to its students.

“Each year, students establish a mentor relationship with a lawyer or judge who introduces them to the realities of legal practice, and at a more fundamental level, facilitates conversations essential to the student’s development of professional identity and skills,” said Judith Rush, director of the Mentor Externship program.

Students develop relationships with their mentors by engaging in activities throughout the year that give them the opportunity to view the professional world, immerse themselves in hands-on lawyering activities and better understand the work that lawyers and judges do; additionally, students have the opportunity to expand their professional relationships with the guidance of mentors and faculty mentors by taking advantage of networking conversations and events, and participating in activities with other lawyers and judges.

The program provides another rich opportunity for students to understand that relationships create unique filters through which professionals view and evaluate analysis, advocacy, policy and services. Students develop a heightened awareness to the social constructs that often drive outcomes more than the usual competencies taught in traditional classroom settings. The School of Law is not traditional in this regard.

“The Mentor Externship program helps students develop the relationship skills necessary for success in any professional context,” Rush said.

For alumna Dapper, the mentor program gave her a glimpse into the working world. “It proved especially helpful in developing my emotional intelligence by providing opportunities for me to observe top attorneys and judges as they built and maintained relationships,” she said.

In addition to their fieldwork, students take a course, guided by faculty mentors, that is focused on developing relationship skills and core competencies.

In addition to the Mentor Externship program, students have the opportunity to create their own externship by working in a judge’s chamber, general counsel office, business setting or nonprofit organization.

Data from the 2012 Law School Survey of Student Engagement supports that the School of Law is on the right track.

“When you look at the data, we’re significantly better in several areas that we care most about – in the ways that our students grow in relational aspects,” Nichols said.

For example, in response to “How do moral judgment abilities of law students change from matriculation to graduation?” and, “How do law students change in assessments of professional ethical identity formation from matriculation to graduation?” St. Thomas law students showed significant progress at both the aggregate and individual levels.

Whereas students both at peer schools and in the “all schools” group in the survey stayed relatively the same during their law school years, St. Thomas law students indicated that their understanding of themselves increased from their first to their third year.

School of Law students scored higher than other LSSSE students in the extent to which their law school experience contributed to their development in writing and speaking clearly and effectively, thinking critically and analytically, working effectively with others, and in solving complex real-world problems.

“All of these categories are statistically significantly better,” Nichols said. “This isn’t random. We’re thinking hard about how to do even better, but we’re happy that there is data showing that what we’re doing is making a difference for our students.”

The School of Law is committed to educating the whole person. Society expects it; the mission demands it. The school’s emphasis on the lawyer as a whole person, encompassing the spiritual, intellectual and social intelligence of its students, helps students to look into themselves and their relationships with others. Their hiring and promotion may depend on their social intelligence. It helps them not only acquire technical and process skills, but more importantly, how to succeed in the profession.

Read more from St. Thomas Lawyer.