"Americans often find agonistic [argumentative] debate of multiple perspectives little short of agonizing. When “debate” and “argument” serve only to discredit the opposition, beating the opponent with whatever tool is at hand becomes a legitimate strategy. The news is filled with these pseudo-debates, causing average citizens to wonder whether participatory democracy is really the best form of government."

I, Liz, am a rhetorician, and this is how I began my 2009 book, Burke, War, Words. The book explored the development of modern rhetorical theory by looking at the efforts to “purify war” of a key theorist, Kenneth Burke, who tried to find a way during World War II not to eliminate debate but make it effective. As I read through the 60-year-old letters between Burke and his close friends, I gradually realized that he could develop a theory of debate as “purified war” because he and his friends were so often in conflict. They ranged from communist activists to conservative professors, and they attacked each others’ positions, called each other names, felt genuinely betrayed by each others’ stances, and yet remained friends. It was this feeling of being so passionately engaged with both the issue and the relationship that they just would not give up that served for Burke as a visceral alternative to the real war raging around him. I saw this theme so clearly as I sat in the archives during our current war, pouring over those long-ago letters, because I was at the same time involved in my own engaged, argumentative friendship with Joe.

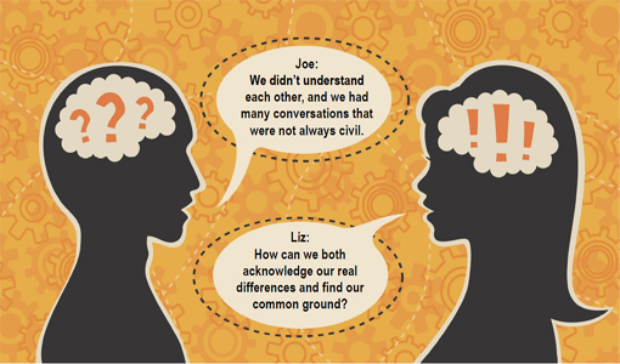

When the two of us think together about “civil discourse,” we don’t start with what might seem to be the obvious question: “How can we as a society politely get along with each other?” Instead we ask ourselves, “How can we as a society engage in full blown useful debate? How can we believe in each other enough to believe that it’s worth it to keep trying to persuade each other? How can we both acknowledge our real differences and find our common ground?”

As a psychologist and marriage and family therapist, I, Joe, see every day the importance of respectful, but honest, discourse that persuades without hurting. In my clinical practice, families come in with relationships fractured from a lack of civility. Some people have difficulty handling conflict in a way that remains respectful of the other; they attack and may eventually create enough damage that the relational bonds can never recover. Other people, however, err too far in the opposite direction; they avoid conflict altogether, so the issues and distance grow and the bonds weaken. We all engage in these behaviors to some extent. When Liz and I rekindled our friendship, at first I made many assumptions about who she was based on who I was 25 years ago. We didn’t understand each other, and we had many conversations that were not always civil.

Both of us had what we thought were our own diverse circles of friends, and we thought we were tolerant people. We knew, however, that certain beliefs were either held in common among most of us or they just weren’t discussed. The two of us “renewed friends” assumed similar commonalities and only belatedly realized that we now had profound differences, deeply felt, and perhaps epitomized by our “Ronald Reagan” conversations. Reagan had been president when we were in the St. Thomas social justice groups, and it turned out that we’d both later had personal contact with his policies. Thus, our increasingly uncivil attempts to explain our strong disagreement, demonstrated by Joe’s agonized note to Liz: “Reagan helped bring freedom to my family in the Czech Republic with his tough-on- Communism policies,” and Liz’s equally agonized note back: “Reagan helped kill my former brother-in-law in Guatemala by supporting death squads.” Reagan (his policies, his era) had saved or ruined the lives of people we loved – how could our friend not see that? Did we not care? With this and endless other differences between us, could we really talk?

For some reason, we did not do “the polite thing” and drop all controversial subjects. That would be the response of Joe’s conflict avoiders, who damage the relationship with the false civility of distance. In Liz’s world of public policy, it would be the times we red- and blue-staters decide there’s no point to seriously discuss together energy policy, war, the economy or the myriad other issues debate-weary people skirt. The two of us instead went around in circles, trying hard not to become Joe’s conflict bludgeoners or Liz’s talk-radio pundits, but instead to be more like Burke’s group of friends, trying to persuade each other and, therefore, trying to believe in each other’s potential as good and rational people capable of persuasion.

Sometimes that didn’t work. Sometimes it still doesn’t. But we are lucky – like the successful families that Joe treats, we shared the desire to respect each other’s opinions before we shared our own opinions. And the more our respect for each other’s core values grew, the more we understood – as Burke had predicted – that underlying our differences are many points of common departure for future discussions. We probably still disagree about Reagan, for instance, but now we recognize that disagreement springs from a common love for people, a common hatred of oppression, a difference in the contexts we’ve personally experienced, and probably a different – equally faulty – sense of Reagan’s influence on world events. It does not spring from a knee-jerk naïve leftist worldview versus a selfish, uncaring rightist worldview. As Liz is fond of noting, Burke insisted that “people, taken by and large, are acting reasonably enough, within their frame of reference,” and when the frame no longer fits, the solution is to widen one’s perspective, not think the other irrational – to see the world not as evil but as misguided and in need of our engaged, respectful, persuasive guidance.

However, with our own new, wider frame of reference regarding friends like us, what we increasingly noticed is that society echoes instead our former polarized conversations. The Left, the Right, environmentalists, businesspeople, Palin supporters, Obama supporters, Tea Party supporters: Groups bond by reassuring themselves how “right” they are and how wrong/evil/stupid the opposition is. We see that columnists, pundits and bloggers make a living lampooning the other side. We share a frustration that politicians spend more time attacking than governing. But we also share a growing awareness that the people in our daily lives, the people we agree with, oftentimes lampoon and attack, stereotype and misunderstand opposing opinions just as much as do public figures. And when the other side is evil, not misguided, there’s no reason to try to persuade them.

We see hopeful signs that others also are becoming aware of this dilemma. St. Thomas’ important new initiative in civil discourse is part of a growing trend. Last spring the president of Ohio State University, where Liz works, called for this largest university in the nation to take the lead in promoting civil discourse in public policy. This fall Joe’s professional group, the American Association of Marriage and Family Therapists, is holding its annual conference with a call to engage in civil discourse about diverse viewpoints on marriage. Liz’s professional group, the Rhetoric Society of America, recently awarded book of the year honors to Sharon Crowley’s Toward a Civil Discourse.

As a nation, we clearly need this kind of civil debate. In Crowley’s book, she cites Chantal Mouffe’s assertion that “a well-functioning democracy calls for a vibrant clash of democratic political positions” and adds that when “citizens fear that dissenting opinions cannot be heard ... they may replace their allegiance to democracy with other sorts of collective identifications that blur or obscure their responsibilities as citizens.” Liz sees this societally with the rise of alienated internet niche groups; Joe works to overcome it on an interpersonal level in his clinical practice: once people feel they are understood, they soften and become more giving, more able to understand in turn.

But he and other psychologists also point out that it is increasingly difficult in our society to create the kind of safe space where such listening can occur. There are demonstrably increasing levels of narcissism that push us away from citizenship responsibilities toward each other. While we usually think of narcissism as excessive self love, it is actually a condition based in shame: narcissists experience considerable internalized shame, and they therefore need to embellish their accomplishments. They are very threatened by criticism. While healthy people can accept their weaknesses and strengths and can admit to being wrong, narcissists need to always be right and therefore need to devalue others. America suffers from a psychocultural “narcissism epidemic,” according to a recent book, and its authors, psychologists Jean Twenge and Keith Campbell, note that “narcissistic personality traits rose just as fast as obesity from the 1980s to the present.” Among a studied group of 37,000 college students, one in four students in 2006 agreed with most of the standard narcissistic indicators. As our culture becomes more narcissistic, we begin to treat each other as objects rather than equals. Being heard becomes more important than listening or understanding. Thus we continue the vicious pattern where being right, blaming and never taking responsibility for fault become the primary ways of “winning” an argument.

And this leads us to the concern we have with the way “civil discourse” is sometimes discussed today.  Rhetoric tells us that persuasion must be predicated on the belief that the other is persuadable – an important first step for civil discourse to occur. However, the two of us worry when the new desire for civility stops there, when what “we” really hope will happen is that “we” will try harder to convince “them,” and “they” will become more open to listening to “us.” (Liz sees this, for instance, even in Crowley’s otherwise fine attempt to open discourse between liberals and the religious.) Our own friendship convinces us that only when we allow ourselves to soften, to also be open to persuasion, can we really engage in the kind of dialogue that strives not to win but to persuade, or in psychological terms not only to be heard but also to listen. This is the kind of discourse that occurs between friends.

Rhetoric tells us that persuasion must be predicated on the belief that the other is persuadable – an important first step for civil discourse to occur. However, the two of us worry when the new desire for civility stops there, when what “we” really hope will happen is that “we” will try harder to convince “them,” and “they” will become more open to listening to “us.” (Liz sees this, for instance, even in Crowley’s otherwise fine attempt to open discourse between liberals and the religious.) Our own friendship convinces us that only when we allow ourselves to soften, to also be open to persuasion, can we really engage in the kind of dialogue that strives not to win but to persuade, or in psychological terms not only to be heard but also to listen. This is the kind of discourse that occurs between friends.

Together we tried unsuccessfully to write our ideas about real discourse for several years before we finally found an unusual format that lets us bring both our professional knowledge and our love of writing together: We started a novel. We did it for fun, initially, and so our novel is a murder mystery and an adventure yarn, with as much humor and action and pathos as we can create. It includes a cast of characters ranging from Harry Chapin (the novel is called Cats in the Cradle) to Kenneth Burke to Pope John XXIII, and its “big picture” plot involves the conspiracy over a lost papal encyclical from Vatican II titled We Humbly Seek the Truth. Locales range from the Midwest to Rome to the Philippines. There’s even a scene at St. Thomas. But the novel also allows us to be serious about our growing shared insights into the vital need to disagree and be willing to change while staying in relationship –even when it’s really hard. Its primary protagonists, then, are the dysfunctional, post-modern “family” of a failed scholar and her former friend, a divorced newly ordained priest, his alienated daughter and her Buddhist brother. It is through them – their continual failure to listen to each other and their endless attempts to try again – that we seek to show just what the abstractions of “purified war” mean in our world. Betrayal, redemption, humility, rightness, narcissism, altruism, division and unity – just as in life – are enacted both on the global ideological stage and the local interpersonal one.

As an example, here is a piece of the St. Thomas scene, in which our protagonists, Luke and Ellie, have been brought back together after nearly a decade to try to help solve the “Cats in the Cradle” mystery:

“We were best friends, Luke. Do you even know how much that meant to me?” Her eyes filled with tears and she looked away from him, over the river, silent a long minute before she could go on. “And when things went wrong you couldn’t even trust me enough to tell me why.”

“It wasn’t about you.”

“No, the reason wasn’t about me. Not telling me the reason, that bloody well was all about me.”

“What do you want from me?”

She frowned. “I want you to treat me the way I’d treat you.”

“You want me to abuse you?”

At that she stamped her foot. “You are oblivious. Don’t you get it? If we’re both biking full speed, me north and you south, and we crash into each other, we’re both injured – but I immediately know that it was an accident so I roll over, ribs broken, and say, ‘Are you okay, Luke?’ But you don’t accept accidents, so you get up, bleeding, without looking at me, and you speed away because one of us had to be to blame. You don’t understand that no matter how many broken bones there are, it’s the speeding away that’s the real hurt.”

“I don’t do that,” he shook his head with finality, denying it all.

As we began to write, a funny thing happened: We realized that the tenets of the “better world” we were envisioning were the theological concepts we’d imbibed as students at St. Thomas. At college in the 1980s, we recognized that we were part of a Church going through enormous changes, still struggling with what it meant to become the Church in the modern world. It was a very exhilarating, very frustrating time – a very alive time – to be a Catholic. And so in our novel, Angelo Roncalli, Pope John XXIII, plays a key role. In order to write “him” (or really, a character that is based on him – we admit freely to playing with history in this fictional account), we’ve been re-inspired by his life and teachings, and this has been, for us, one of the best parts of our research. His novelistic nemesis is an anti-Modernist secret society (which actually existed at the time of Pius X) that will go to any length to eliminate a challenge to their view of Catholicism.

Here, for instance, is a bit from the first meeting of Burke and Pope John in 1963:

[Pope John XXIII] “I am no scholar, no intellectual. I am a man of the people, a paisano – a farmer, yes, but always I have believed that a peaceful man does more good than a learned one.”

Burke relaxed visibly, grinning broadly at the pope. “I live on a farm,” he said. “I don’t have a college degree. I believe in starting from words and actions, not abstractions. And all my life I’ve tried to say that people act reasonably if you understand their point of view.”

As we write and work in our respective professions, trying to help people engage in “effective dialogue” or “respectful listening” or “civil discourse,” we find that the ideas and ethics we learned a quarter century ago at St. Thomas still inspire us. Liz was at the Chapel of St. Thomas Aquinas on Memorial Day, using a quick visit home to scope out a scene for the novel. (A good thing too – how did the whole building manage to turn itself in the opposite direction from our perfectly clear memories?!)But some memories were stronger. Up in the choir loft, the ghosts of the Liturgical Choir in which Liz had sung filled their chairs, lifting their voices to sing for a Sunday morning Mass the song of another alumnus, Marty Haugen: “Gather us in the lost and forsaken. Gather us in the blind and the lame. Call to us now and we shall awaken. We shall arise at the sound of our name.” This desire for unity is the lesson we learned from St. Thomas, the reason that we think civil discourse has a natural place at this university. Grounded in the Spirit at its best, religion shows us how to bond together, not in pride but in the hope that we can persuade others of what we believe to be true and the humility to believe that they may already have some of that truth. “We are the young, our lives are a mystery. We are the old, who yearn for your face. We have been sung throughout all of history, called to be light for the whole human race.”

And so, no longer young, not quite yet old, we write together, striving to bring to life the visions of John XXIII, Kenneth Burke and Marty Haugen and the cloud of witnesses who have made us the people we are today. We won’t always get it right indeed, Joe once said that the thing that makes our friendship like family is that we fight like cats and dogs – but we strive to overcome our failings and continue the dialogue, the unending conversation. It is so easy to be certain that our opponents will never have our morals or be compelled by our logic. But as the University of St. Thomas, our alma mater, taught us, it is better to sing a song together with other imperfect people than to sing it alone perfectly: “Gather us in the rich and the haughty. Gather us in the proud and the strong. Give us a heart so meek and so lowly. Give us the courage to enter the song.”

Read more from CAS Spotlight