KAMPALA, UGANDA - The miracle workers are busy here these days.

In a former retail storefront on a rut-filled dirt road in Ndejje, a poverty-stricken area southeast of Kampala, the first Hope Medical Clinic opened in November 2007. The sign outside says "Eddwaliro," Ugandan for "health care," in bold red letters, and 40 to 50 people show up every month or treatment of malaria, typhoid fever and the flu.

In an abandoned house two blocks off Kasubi Road, a bustling north Kampala thoroughfare jammed with merchants selling food, a second Hope Medical Clinic opened two years later. Patient No. 2,000 walked through the door in early January.

And three miles away on Bombo Road, the Ruth Gaylord Maternity and Pediatric Hospital is taking shape on three acres of land donated by the Archdiocese of Kampala on the grounds of Jinja Kalori (Built on a Rock) Church. Two buildings are complete and will open in March, and construction will begin on a third building when funds are available.

These are impressive achievements - the result of efforts of a St. Paul priest disturbed by the lack of quality health care for the poor, a native Ugandan overseeing every detail of operations pro bono, and dozens of generous Minnesota donors. Everywhere you go and every person you talk to, one word seems to be repeated over and over: miracle.

"This is testimony for how miracles happen," Monsignor Charles Kasibante, vicar general of the archdiocese, told an audience of 200 people on a mid-January day at a formal blessing of the hospital. "This hospital was not only wanted here but it was needed, and lives will be saved."

"I didn’t expect the hospital to be this big," said Father Richard Kakoma, pastor of Jinja Kalori. "People are very happy about it. They call it a miracle."

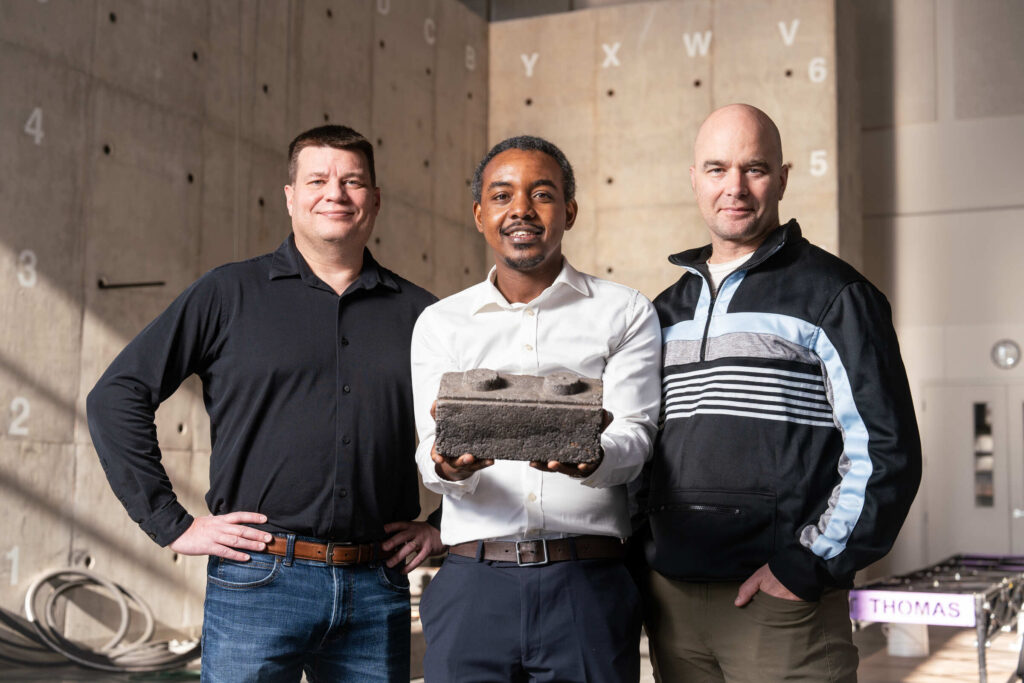

"This man is a miracle worker," said Father Dennis Dease, president of the University of St. Thomas, as he points to Charles Lugemwa ’03, a St. Thomas master’s in software engineering alumnus who lives across Bombo Road and supervises the hospital’s construction. "With his abilities and my big rosary, we are going to complete this project!"

The crowd laughed as a translator restated Dease’s remarks in Ugandan. He held up a wooden rosary seven feet long and with beads two inches in diameter. "This is the biggest rosary that I have," he said, "and I’m going to need a really big rosary to raise the rest of the money" ($90,000 is needed to construct the third building).

The ceremony ended in song and dance, and people wandered through the buildings. Dozens waited for free immunization shots or fittings for hearing aids; 5,330 were donated and delivered in March in Kampala by the Starkey Hearing Foundation of Eden Prairie. Visitors marveled at the size and scope of the buildings, and Dease and Lugemwa found themselves in an unfinished room reminiscing about how the project began.

Dease never intended to become a health care entrepreneur in his spare time, but one day several years ago a Twin Cities businessman told him about "minute care" clinics that he wanted to establish in his native Ghana. He asked Dease to look at the clinics and he said yes - but only if the businessman would continue on to Uganda with him to ascertain the possibility of clinics there.

Dease turned to Lugemwa, a Uganda Revenue Authority administrator already helping St. Thomas by identifying prospective undergraduate students, to develop a business plan. Lugemwa admits he was "scared" by the challenge, "but then I prayed over it, and I realized we could do it."

"The Ghana model was more like a business, a franchise type of approach," Lugemwa said. "Ours is not a franchise; it’s the idea that the community sustains the facility. We employ professionals to run the facility and the people around it sustain the facility."

Lugemwa also was attracted to the project for personal reasons. His baby daughter died several years ago because she received the wrong medication.

"The way I could contribute was to make sure that did not happen to any other person,"he said. "With our clinics, we’re preventing that from happening."

Lugemwa had friends who, when hearing him describe the clinics project, would say, "I think this guy is mad." So, was he crazy? "Yes, sometimes!" he said with a smile.

The Ndejje location has struggled to break even because of its location; the lower income of residents, many of whom are subsistence farmers; and the higher costs of doctors whose travel expenses need to be reimbursed. Consequently, modest profits from the more successful Kasubi clinic have subsidized Ndejje.

"We made mistakes," Lugemwa said. "If I were to choose a site again for a clinic, I still would choose Ndejje, but that was a learning point. We wouldn’t give up just because we selected the wrong site. We benefited in terms of the knowledge we gained."

Four employees staff Kasubi. An administrator, two nurses and a laboratory technician work fulltime and receive free lodging and two meals a day, and a doctor drops in to check on patients. Lugemwa calls or visits regularly, too. The renovated house has a reception room with a small pharmacy, overnight rooms for men and women (two beds each), a laboratory and a pediatric ward.

Administrator Daphine Namyenya, 27, was the clinic’s first employee and makes 250,000 Ugandan shillings ($125) a month. She oversees the staff, patient files and appointments, prepares monthly financial statements and keeps meticulous handwritten records; there are no computers. She is proud to open a ledger that shows the clinic treated 153, 178 and 100 people the last three Decembers; two-thirds were first-time

patients and the rest were returners.

"Those are great numbers," Lugemwa said. "It shows the need for a place like this. We always want more new patients, and when they return, that shows we are doing a good job."

The clinic had two patients the morning of the January visit by a St. Thomas delegation: a young girl with malaria and 56-year-old John Tibenkna, who lives in the neighborhood and came in at 2 a.m. with a high temperature, an upset stomach and the sweats. Namyenya, who lives upstzairs, summoned a nurse from an adjacent apartment building and they put him on an IV.

"This is a good clinic," Tibenkna said. "My family members have been here - my children and grandchildren. They are taking very good care of me."

Lugemwa said Tibenkna was a typical patient in terms of his illness - most patients have malaria, typhoid fever or diarrhea - and the clinic’s treatment philosophy.

"Other clinics do not have lab facilities," he said. "They treat you without knowing the illness you have. It is trial and error. We insisted on having a lab here. Before you are treated, you are tested. We also don’t want to have to refer them to a hospital. That means the patients will need to pay more than they can afford, and it’s like you are condemning them."

Over time, Dease and Lugemwa realized the need for just that - a hospital. The conditions for pregnant women at Mulago, a large public hospital in Kampala, shocked Dease.

"For me, it was something like out of horror movie," he said. "Mothers were giving birth on the floors in rooms and in corridors. It was really a very disturbing picture, and that was what prompted us to decide to find a better way to serve mothers in delivery. I think Charles captured what the mission of this hospital is when he said our motto should be, ‘Every mother goes home with a healthy baby, and every baby goes home with a healthy mother.’"

A hospital, however, would be expensive. As plans were drawn up and the price tag jumped over $200,000, Dease mulled over ways to raise funds. Monsignor James Habiger, the retired Minnesota Catholic Conference executive director who lives at St. Thomas, became aware of plans for the clinics after reading a Dease column about Lugemwa in the fall 2008 issue of St. Thomas magazine.

"The hospital will become a model for the rest of the country in terms of care for women and then for their children," Habiger said. "It will save so many lives."

"I didn’t ask him for money," Dease said. "He came up to me one day and said, ‘I want to be part of it.’ He has been very generous, as nhave others. Roberta Mann Benson (another benefactor) spontaneously told me one day that she wanted to make a substantial contribution."

Habiger, as the lead donor, asked Dease if the hospital could be named for Ruth Gaylord, a lifelong friend who taught music in Minnesota schools during her career. She was flattered and embarrassed by the attention, but an acquaintance told her she was being "too Minnesotan." Describing herself as a "plain, ordinary woman," she asked Habiger why her name should be on the hospital.

"And he told me, ‘Because I want women in Africa to know that a plain, ordinary woman in America cares about them.’"

Hope for the City, a Minnetonka-based nonprofit that distributes corporate surplus materials around the world, has donated $800,000 in medical equipment, supplies and furnishings to the clinics and hospitals.

"When Father Dease started talking about what he wanted to do with the clinics, we wanted to be part of it," said Megan Doyle, co-founder of Hope for the City with her husband, Dennis Doyle, chairman of Welsh Companies, a Twin Cities real estate firm. "We said, ‘Let’s do it.’"

Brian Mark, president of RBC Tile & Stone in Plymouth, Minn., is another benefactor. He donated all of the floor and wall tile for the hospital buildings as well as funds for a wall around the hospital grounds because he thought it was important to be involved in this kind of humanitarian effort.

Gerald Schwalbach, a Twin Cities real estate developer, and his wife, Sue, made donations for the hospital’s labor and delivery room and a convent and chapel that will be built on the property.

Dease and Lugemwa knew how important it would be to hold down hospital costs, and they came up with an idea on how to avoid acquiring land, paying rent and holding a mortgage.

"Uganda is 90 percent Christian, and there are churches all over the country," Dease said. "We put two and two together and we approached the Archdiocese of Kampala. The archbishop said he would donate three acres of property from this parish, Jinja Kalori, for us to build our hospital.

"Then we began to realize other advantages to being associated with a very large parish. One of those is instant marketing. Another is instant credibility, because not all health service providers here are people of good will and not all the pharmaceuticals distributed are bona fide. We also realized that the parish would be a source of volunteers who could go out and teach people about water, mosquito nets and the importance of child immunization."

A final advantage is the hospital’s interaction with the Catholic Church - a tradition that Americans have valued for more than two centuries. The Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary Reparatrix, founded in Uganda in 1948, will staff the hospital.

"The African people tend to see healing as not just a physical reality but also a spiritual reality ... that spirit is an active agent in a person’s recovery," Dease said. "That became another plus in terms of putting this hospital next to a church."

Dease also is delighted that Dr. Timothy Schacker, a 1978 St. Thomas alumnus who is director of the Infectious Disease Clinic at the University of Minnesota, will be involved. Schacker has made more than a dozen trips to Uganda over the last five years to do research on why drugs for HIV-AIDS patients have different outcomes on Ugandans and Americans.

"There will be opportunities for our medical students in residency to assist at the hospital and participate in what Charles and Father Dease are creating," Schacker said. "Their model is interesting because it’s sustainable. It could be a game changer in medical care in Uganda."

As hospital construction continues, Lugemwa and Dease are grateful for many things.

Lugemwa talks about how, next to his family, the greatest gift he has received in his lifetime "is the gift of education - a gift that makes me do what I do" - and he credits St. Thomas with imbuing in him the spirit of volunteerism.

"I never did this before. I used to see so many people get involved in community service work, and I love it," he said. "You can have money, but you might not be happy. I do this, I don’t get any money, but I feel happy. That’s what life is - it’s not just about money."

Dease nods as Lugemwa speaks and says his friend’s greatest gift is that "he embodies as much as anyone I’ve met the mission of St. Thomas.

"How do you count the value of the lives that he already has saved, and will save?" Dease asked. "He serves the common good. That’s what St. Thomas is all about, and the day we forget that is the day the lights go out."

Read more from St. Thomas magazine