Imagine a group of chemicals so useful they’re in everything from your phone to your clothes, but they never break down and could be harming your health for generations. These chemicals do exist and there is not enough money in the world to remove them from the environment as fast as they are being added.

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS, aka “forever chemicals”) are a group of over 10,000 very useful chemicals. They support high-precision semiconductor manufacturing, make clothing more water-resistant and makeup more smear-proof, reduce friction in nonstick pans and medical devices, and mitigate fire risk. Because they are so useful, they are nearly ubiquitous in consumer and industrial products, and have been detected in nearly every living thing on the planet. However, the same characteristics that make them useful also mean that they are very resistant to being destroyed and do not break down in the environment. In addition, some PFAS have been found to negatively impact human and environmental health.

PFAS and persistence

Their environmental persistence means that PFAS humans put into the environment will stay there unless they are actively removed. They don't “go away” in the environment. They will keep building up as long as society continues to make, use and release them.

While I am worried about the health risks associated with PFAS right now, I am really worried about health risks for PFAS 100 years from now, given the rate at which the mass of PFAS in the global environment is growing.

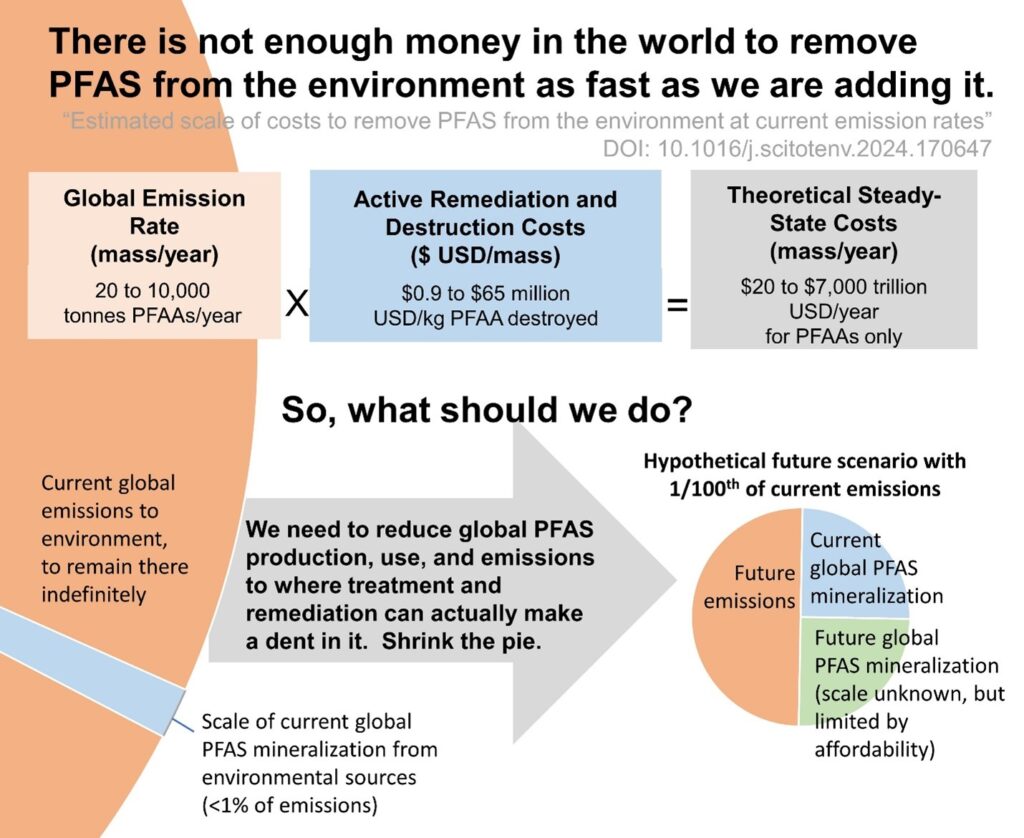

I recently estimated how much it would cost to remove and destroy PFAS from the environment at the same rate they are currently being emitted. My estimate is much higher than the current global GDP. This means that there is not enough money in the world to remove PFAS from the environment as fast as they are being added. Treatment alone cannot be relied upon to control environmental PFAS – humans need to make and use and emit less of it, and by several orders of magnitude.

PFAS source reduction and substitutions

If we don’t want environmental PFAS buildup to continue spiraling out of control, with compounding health impacts for future generations, we need to shrink the PFAS emissions pie enough for treatment applications to make a difference at a cost that doesn’t bankrupt the global economy. Luckily, the vast majority of PFAS uses have readily available alternatives right now.

St. Thomas’ local neighbor, 3M, set a good example by committing to end PFAS production by 2025. Many retailers, including H&M, KEEN, Patagonia, and IKEA, have committed to removing PFAS from their supply chain and products. But more consumer and regulatory action is necessary to accelerate PFAS use restrictions.

The PFAS ban passed in Minnesota last winter is another good start. Also called Amara’s Law, it requires companies to remove “intentionally added PFAS” in 11 product categories with readily available alternatives by 2025. This ban expands to remove all nonessential uses of PFAS except those that are “currently unavoidable” by 2032.

Everyday consumer actions to support PFAS phase-out

Three things you can do right now to help:

- Use your purchasing power to support retailers and companies working toward a PFAS-free supply chain. The Environmental Working Group and others maintain lists of these companies, sorted by product type.

- Protect your family’s health by choosing PFAS-free clothing, bedding, cosmetics, cookware, contact lenses, rugs and carpets, and other high-contact, everyday use products. Be aware that PFAS-free products may not perform as well as products with PFAS, at least for a while as companies continue to develop alternatives and rework their supply chains. Be patient with your local retailers as they work through this!

- Learn more about PFAS and other persistent environmental pollutants, then advocate with family and friends about how PFAS use restrictions protect current and future generations from the compounding impacts of ongoing PFAS pollution.

The future is bright as PFAS bans are being considered in more jurisdictions and product categories. Ongoing work will be needed to continue to develop alternatives, phase out PFAS from supply chains, and promote PFAS regulations on a global scale.

Ali Ling is an assistant professor in the Civil Engineering Department in the School of Engineering.