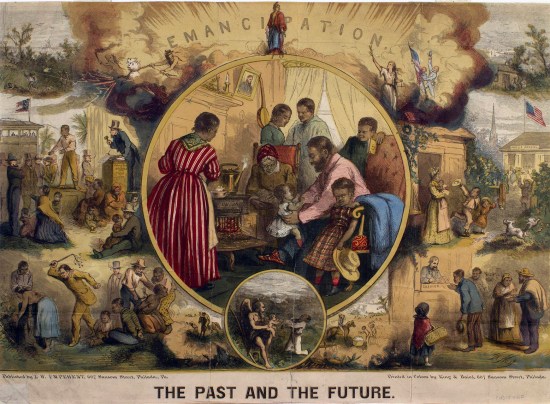

For the first time in its history, the University of St. Thomas will honor Juneteenth as a university holiday. June 19 commemorates the moment at the conclusion of the Civil War when Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger issued an order proclaiming the freedom of formerly enslaved people in the state of Texas — the last state of the former Confederacy (though not the last in the United States) in which the United States military would declare that slavery was dead and that enslaved people were now free.

Yet the story of Juneteenth’s origins fails to convey its significance as a day of celebration and of remembrance. By enforcing the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared that enslaved people held captive by those living in Confederate territory would be “now, henceforth, and forever free,” the United States military broke with more than two centuries of government-sanctioned human bondage. In 1850, the Fugitive Slave Act had made it a felony for any U.S. citizen to anyone attempting to escape from slavery, thereby securing the institution of human bondage into federal law. Shortly thereafter, in 1857, the Supreme Court issued its infamous Dred Scott decision. That decision not only explicitly acknowledged that possession of slaves as human property was an inalienable right of white Americans, but also made it impossible for African Americans to become citizens. The court wrote that Black people were “not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word ‘citizens’ in the Constitution, and can therefore claim none of the rights and privileges which that instrument provides for and secures to citizens of the United States.”

When the Civil War broke out over the political future of slavery in the United States, African Americans took action to demand that the United States reconcile its professed love of liberty with its horrific legacy of radicalized human bondage. They ran to Union Army lines and escaped from slaveholders throughout the South, using their knowledge and their labor to aid the United States war effort from its earliest days. Beginning in 1863, nearly 200,000 Black men would enlist in the United States Army. They would use their service to give the lie to Dred Scott and its white supremacist vision of American society, proving that in the words of Frederick Douglass, “He who fights the battles of America may claim America as his country — and have that claim respected.”

Juneteenth is not only a celebration of the arrival of freedom, but of the too often unstudied history of African Americans’ role in making American freedom real for themselves and for all citizens.

In the decades that followed the end of slavery, the meaning of emancipation would come under attack from many directions. Immediately after the Civil War’s conclusion, the United States government would change its laws in unprecedented ways. The 14th Amendment would establish that all persons in the United States had claim to equal citizenship, paving the way for a legal revolution. But the backlash against that promise would be powerful and overwhelming, using a combination of political ideology and overwhelming violence to repress African American ambitions for equality. By the end of the nineteenth century, the Supreme Court would declare in Plessy v. Ferguson that “Legislation is powerless to eradicate racial instincts or to abolish distinctions based upon physical differences, and the attempt to do so can only result in accentuating the difficulties of the present situation. … If one race be inferior to the other socially, the Constitution of the United States cannot put them upon the same plane.” That decision and others like it would usher in decades of racial segregation, economic oppression and horrific violence — legacies whose damage left profound scars on our nation that endure to this day.

Thus, the meaning of Juneteenth remains contested. As a testament to the wrongs of slavery and a celebration of African Americans’ role in bringing about its end, Juneteenth is a powerful statement of ambition and hope. As a challenge to succeeding generations — including our own— to avoid repeating the mistakes of a generation of Americans who emancipated themselves from the problem of turning the end of slavery into actual freedom and an enduring racial equity, Juneteenth is a call to action and to vigilance.

The following represent the unedited views of University of St. Thomas students who grappled with the complex meanings of freedom and emancipation in History 396 — The Long Emancipation during the spring 2021 semester. Drawing upon their time together in that course, they offer the following reflections on Juneteenth’s importance to the lives of Americans today:

Nasteha Ahmed ’24:

The first time I read the Emancipation Proclamation in its entirety, I felt chills go down my spine. I can only imagine that this intense feeling was felt more heavily by the slaves in Galveston Bay, Texas, on June 19, 1865, as the words “free” and “slave” were uttered in the same breath. Such was the power of the Emancipation Proclamation.

However, emancipation is a term often thought of as synonymous to freedom. While the Emancipation Proclamation did grant freedom to slaves on paper, the reality of what freedom entailed was equivocal and enigmatic in the sense that it did not have a clear forged path. Many African Americans who were former slaves were suddenly living in a society that did not even define the terms of citizenship for them yet.

Despite that, the reasons for celebrating Juneteenth are far too imperative. It is a celebration of resilience. It recognizes the struggles that African Americans have had to face for centuries in the harsh era of slavery. It demonstrates the epitome of what a community is – the ability to come together and face hardships collectively and come out of the other end stronger. For so long, African Americans were denied the opportunity to be seen as men, but the Emancipation Proclamation was the first stop in the journey to equal citizenship and this is why Juneteenth is important to recognize. It is a reminder to our nation that we must continue to fight for what is right and just.

Alessandro Knutson ’23:

Emancipation through war, and the even more consequential project of post-war Reconstruction, redefined the U.S. With hindsight it is easy to conclude that emancipation was inevitable, and more critically, that emancipation with citizenship was as well. By no means was it.

Emancipation by the time of the Civil War could have meant a lot of things. It could have meant a re-emergence of the colonization schemes of Henry Clay and James Monroe, where America would have sent its black population across the Atlantic and back to Africa. It could have meant the Black Codes, where freedmen would have simply become slaves in all but name. And it could have been a million things in between. But it was not. Where the Founding Fathers and politicians of the early American republic had failed, war succeeded.

Offered the chance to enlist and fight for the Union, hundreds of thousands of African Americans did, in the process redefining the very war itself. Rather than a narrative of the benevolence of the Lincoln administration and white elites, emancipation is the story of how African Americans managed to change the trajectory of the U.S. through fighting a war that initially seemed to want to be about anything but slavery. That this came often at the cost of their own lives on the war’s many battlefields, or in the contraband camps of the Upper South, should not be forgotten. When the South attempted to simply re-enslave African Americans through the post-war Black Codes, it was Congress who defied President Andrew Johnson by stepping in and passing the first of the Reconstruction Acts. That they would do this in the name of repaying the service done by African America troops is proof more than anything that the U.S. had changed after the war, and that this new era of often unreliable accountability offered to Freedmen could be traced back to the Civil War’s emancipation.

Diego X. Luke ’21:

Since the ambiguous statement made by the Founding Fathers, “we the people,” the United States has gone through a variety of changes both ideologically, ethnically and geographically. The United States has used hyphens (African-American, Italian-American, Mexican-American, etc.) as a way of division, while still emphasizing and recognizing diversity within the United States. Accompanying the ethnic diversity within the United States are the celebrated holidays of the United States, and Juneteenth is one of them.

Juneteenth represents the United States acknowledgement of the history of slavery, and the impact it had on those who suffered it and those who are products of slavery. Juneteenth is a step in the right direction in terms of racial equality. However, it perhaps creates more of a question than an answer on how to deal with the fallout of slavery. Acknowledging slavery is just the first step in the healing process for all Americans. Yet the pain in Black communities can still be felt to this day, so emancipation was as simple as being freed, but is rather an enduring process. Simply put, having a holiday in remembrance of slavery is not satisfactory, there needs to be more work done politically and socially.

Ensign Tori Szondy, USN ’21:

Emancipation’s legacy, and thus, Juneteenth’s legacy, is one of selflessness in the face of extreme suffering. Enslaved black people built the Cotton Kingdom with their blood, sweat and tears. Despite the conditions they faced, Black people built a rich and beautiful culture that permeates American society today.

Freedpeople in particular in the both the North and South enlisted into the United States military with full understanding that they were up against an enemy who hated their existence and were employed by an entity that saw them as untrustworthy and expendable. Over the course of the war, Black service members were paid less, given less equipment and suffered higher casualty rates than their white counterparts. Even so, freedmen knew that emancipation was a cause worth fighting, and suffering once again, for.

The 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment, an all-Black regiment headed by a white colonel, demonstrated extreme selflessness and bravery during the assault on Fort Wagner. Keep in mind that this fort was designed to repel a frontal assault; only after the 54th Massachusetts suffered from a higher than 50% casualty rate did the Union commanders order a retreat. It was then decided that they would siege Fort Wagner via the sea. Despite their high casualty rate, the 54th Massachusetts were ushered to the next deadly mission while white regiments were rotated home.

As a white service member, I stand in awe of the bravery that these men demonstrated in the face of evil. It is not often a soldier or sailor has to fight against both the enemy and the organization employing them. I would like everyone to reflect on the contributions of Black service members this Juneteenth, and if we all can embody a fraction of their selflessness, this world will be left a better place.

Sophia Hernandez Tragesser ’21:

The American founding launched an ambitious test of people and politics, with the intent of producing a coherent people living together for the betterment of their Union. However, the founders of this American project willfully left a cancer on liberty and humanity by failing to end slavery. The presence of slavery left a conflict between American ideals and reality observed by all, yet tactfully left unaddressed by politicians for decades. The egregious presence of slavery left the American project in dissonance until emancipation. Emancipation was the product of years of advocacy by African Americans and abolitionists, hundreds of thousands of American lives sacrificed during the Civil War, and the efforts of enslaved people across the United States who risked their lives to enter the threshold of liberty during and after the war. Commemorating Juneteenth as a day, and with it emancipation as a bloody and laborious process undertaken by African Americans, honors their lives. Further, it commemorates the fulfilment of ideals of human dignity, liberty and union, and is the most substantial step taken toward “a more perfect Union.” Emancipation was the beginning of coherence in the ideals of Americanism, and as the starting point, was surrounded by a bevy of cultural and social hostilities threatening the lives and prosperity of African American communities. Commemorating Juneteenth notes the triumph and tragedy of a pivotal moment in American history. By popularizing a basic understanding of emancipation, American can begin to understand the transition from slavery at a national and individual level, and realize the transformative moment, and along with it the missed opportunity to fully reset the course of the nation as a polity containing a multitude of races, unrectified until the civil rights movement.