Free and fair elections are the cornerstone of democracy, but recent U.S. elections have faced two major challenges: the spread of political misinformation and long voting lines. As it turns out, there may be a connection between the two.

According to new research, areas of the country with longer voting lines have the lowest level of confidence in the voting process – and this is leading to an increase in the spread of misinformation. Even more concerning is that these effects are disproportionately concentrated in minority communities, which already face barriers to political participation. This suggests that operational inefficiencies not only create logistical challenges but also erode trust in the electoral process, particularly among vulnerable populations.

Misinformation, often shared via social media, has become a significant concern, distorting perceptions of election integrity and potentially affecting outcomes. This was especially clear in the 2016 and 2020 presidential elections, when false claims about voting systems circulated widely, undermining public trust and contributing to the unrest leading up to the Jan. 6 Capitol riot.

Meanwhile, long voting lines have emerged as a persistent issue. In states such as Arizona, Florida, and Ohio, voters have faced hours -long waits during critical election periods. For example, Arizona’s 2016 primary, wait times reached five hours for some voters. This problem was prevalent during the 2012-20 elections, with 9%-14% of voters waiting over 30 minutes nationwide.

What causes long voting lines?

Long voting lines often stem from poor planning and inadequate resource allocation. Insufficient voting machines, poll workers, or poll books can create significant delays and disenfranchise voters. From a queuing perspective, the problem arises when the number of voters arriving exceeds the capacity of polling resources to process them. The greater this imbalance, the longer the lines.

Voting at a polling station can be viewed as a three-step process: checking in, casting a ballot, and scanning the completed ballot. Delays at any of these stages– whether due to bottlenecks at check-in, limited ballot-marking devices, or insufficient scanners– slow down the entire system. For example, in the 2012 election, Florida and Maryland saw precincts with fewer machines or poll workers, leading to longer waits.

Common issues like consolidated polling stations, recently seen in Wisconsin and Georgia, in addition to confusion over new voting requirements and machine failures, also contribute to longer wait times. Changes in election laws, such as stricter photo ID requirements or limited early voting options, slow down the process, as well. These changes additionally hinder experienced poll workers from effectively training recruits, exacerbating the poll worker shortages many states are already facing.

Unfortunately, voting resources are frequently allocated using overly- simplistic methods, such as distributing machines proportional to the number of registered voters, which can result in uneven wait times across counties. While more sophisticated methods for resource allocation exist, election officials need to adopt such scientifically proven models to optimize the distribution of voting resources. Unfortunately, many jurisdictions struggle to implement these solutions due to limited funding and personnel.

Rise in fake news belief

Long voting lines are not just a barrier to voter turnout and accessibility; they may also fuel the spread of political misinformation. Long waits at the polls can lead to frustration and cynicism, making voters more receptive to false narratives, especially those questioning election legitimacy.

Using smartphone location data and geo-tagged posts from Reddit, our research team tracked county-level voting wait times and quantified the prevalence of political misinformation around the 2016 election nationwide. The findings revealed that counties that experienced longer voting lines in the election saw a significant increase in the sharing of political misinformation on social media in the months following the election, with a 10-minute increase in wait time leading to a 16.2% rise in fake news posts.

Their analysis shows that voters who experienced long waits are more likely to believe in widespread voter fraud and view hacking as a major concern. Interestingly, these effects are primarily local. Long wait times tend to erode confidence in vote counts for their own ballots or within their county, but don’t significantly impact views on national vote counts.

Minority communities are hit harder

Even more concerning is that these effects are disproportionately concentrated in minority communities, which already face barriers to political participation. Black voters, and even more so, Asian voters, are especially vulnerable to how poor voting experiences can heighten susceptibility to misinformation.

The research shows that the impact of long wait times on the spread of fake news increases as the proportion of racial minorities in a county rise. For example, in a county where 20% of the population consists of racial minorities, a 10-percentage-point increase in voters experiencing long waits correlates with a 38.3% increase in fake news posts, relative to the average. In a county with 50% racial minorities, that same scenario leads to a staggering 333.8% increase in misinformation. The study also highlights distinct variations across racial groups, with Black and Asian communities experiencing particularly strong effects.

Less trust in the electoral process

Voters who experienced long waits are more likely to believe in widespread voter fraud and view hacking as a major concern. Our analysis of the individual-level data from the 2016 Survey of the Performance of American Elections shows that voters who waited more than 10 minutes in line were significantly more likely to see hacking as a major issue at the local level, with a 39% increase in the odds. Additionally, voters who faced long waits were more likely to doubt the accuracy of the vote count for their own ballots (a 62% increase in odds) and to question the vote count within their county (a 54% increase in odds). Interestingly, these effects are primarily local, but don’t significantly impact views on national vote counts.

Combating misinformation

The implications of these findings are troubling. Long voting lines are not just a matter of inconvenience– they have far-reaching effects on voter confidence and the spread of misinformation. While much attention has been given to combating fake news through content moderation on social media platforms, this research highlights the need for a more holistic approach. Election administration itself may play a crucial role in mitigating the spread of misinformation by improving the efficiency of voting operations.

To address these challenges, election officials must prioritize better resource allocation at polling stations, especially in minority communities. Scientific models and simulation techniques for optimizing voting processes should be implemented more widely, rather than relying on outdated and simplistic methods. By improving the efficiency of polling operations, we can not only enhance voter convenience but also strengthen trust in the electoral process, fortifying democracy against the corrosive effects of fake news.

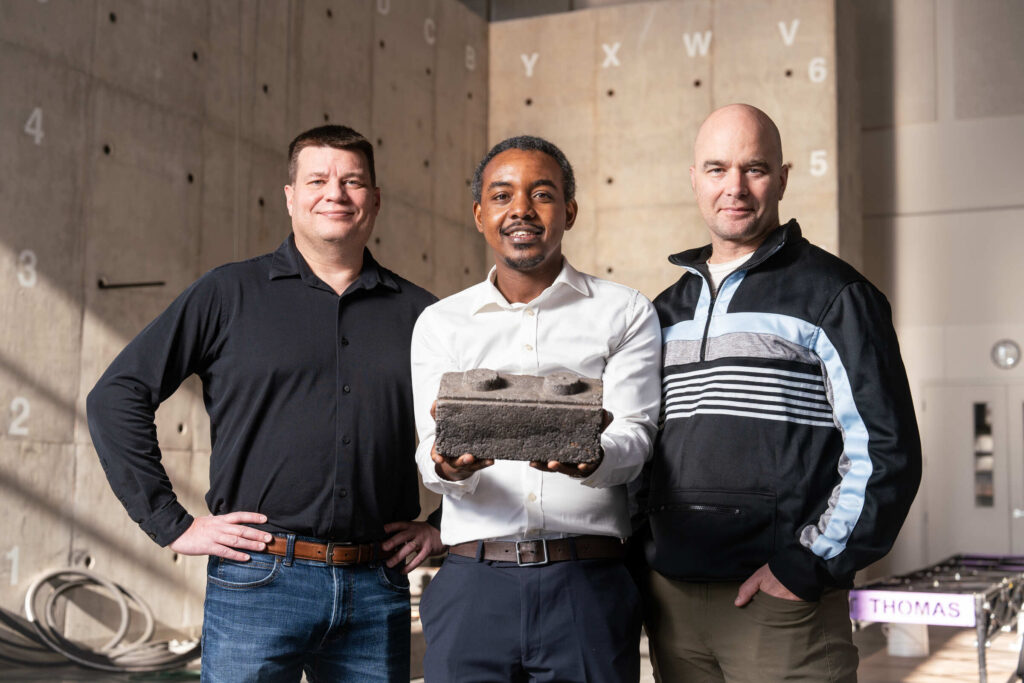

The new research mentioned in the article, The Queue-rious Case of Misinformation: Voting Wait Time and Spread of Fake News, is a joint work by Professor Muer Yang, Professor Mai Feng (University of Iowa) and Professor Jingyi Sun (Stevens Institute of Technology).

Muer Yang, PhD, is a full professor in the Department of Operations and Supply Chain Management at the University of St. Thomas Opus College of Business and an expert in election operations. His research focuses on areas with high social impact, particularly operational challenges in the public sector, such as elections, humanitarian logistics, and healthcare. His work has been published in leading journals, including Production and Operations Management, IIE Transactions, Omega, and the International Journal of Production Economics. Yang's research on election operations has garnered media attention, and he has served as an expert witness in several election law cases.