To help assess whether job applicants should be interviewed or not, Amazon generated an algorithm that picked out resumes most similar to the company’s most successful job applicants.

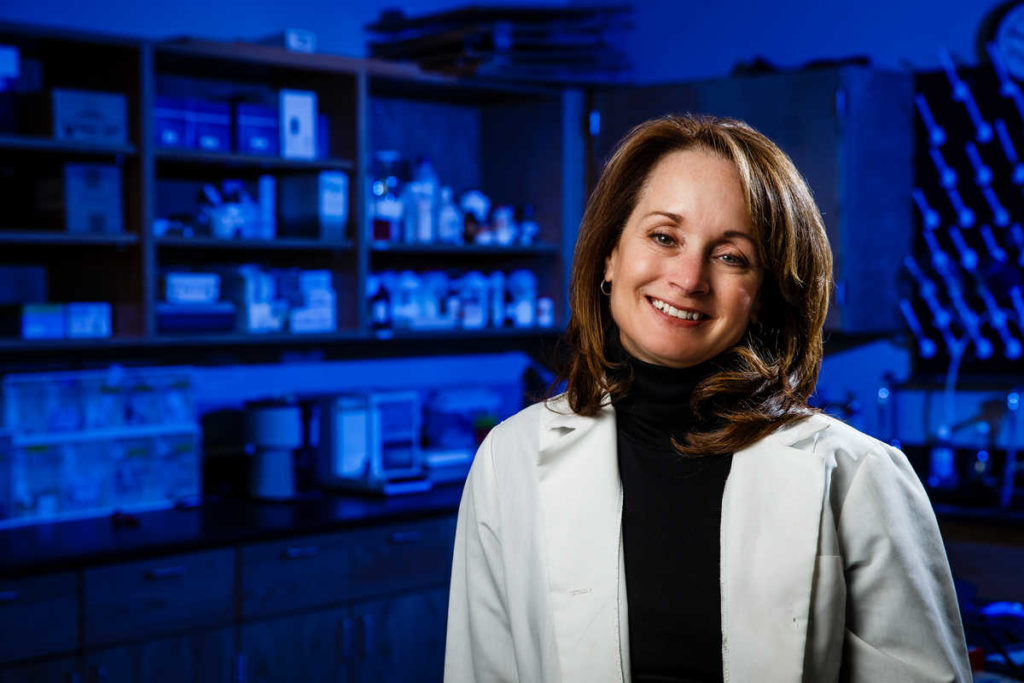

Amelia McNamara, PhD, a computer and information science professor at the University of St. Thomas, said this seemingly benign innovation for hiring wasn’t as forward-thinking as it seemed, and Amazon eventually stopped using it. Why? Because most of the successful job applicants in the past were male, leading to bias in the algorithm’s decisions, specifically against women.

“Algorithms are used in social media, self-driving cars, online advertising, child protective services, by loan offers, and more,” McNamara said in a recent Teach-in Tuesday discussion focused on the impact of data-driven algorithms and the tools that can be used to push back against them when these technologies reinforce biases in society and keep us stuck in the past.

An algorithm, McNamara explained, is a set of instructions to achieve a specific goal. The trouble, she said, starts with the data, numbers, pictures, text, user behavior or more used to help the algorithm make predictions. Either because more men had applied for jobs at Amazon or because of human bias in interviewers, data told Amazon’s flawed algorithm that most successful job applicants were male, so the algorithm penalized resumes that contained the word “women’s” in them.

If the algorithm decides someone shouldn't get an interview, they may not be able to get a job. Algorithms used in education to detect cheating based on eye movement can be biased against people with blindness or ADHD or even parents who must keep an eye on kids while taking a test from home. Take any number of the algorithms being used to make decisions, and it’s clear they’re impacting lives in real ways, McNamara said, also citing the recidivism risk scoring algorithms used in the justice systems.

When it comes to using historical data about crime, “these algorithms can be used to decide if people are let out on bail or held in jail while awaiting trial, whether they get imprisoned or are let off on parole,” McNamara said. “And those are huge, life-changing decisions.”

The intention behind these algorithms was good, McNamara said. Human judges are often biased. She said humans have conscious or unconscious bias that might impact how they sentence people, while a machine could be more neutral.

“However, this algorithm is based on data, and the data comes from our judicial system, which has historically been biased against people of color in terms of more policing, more arrests, more convictions for minor crimes. If you feed that data into an algorithm, it's going to reinforce that bias into the future,” McNamara said.

Reports show these kinds of biased algorithms aren’t accurate predictors. Journalists tracked, post-arrest, a white man and a Black woman who were charged for the same crime of petty theft but given different sentences.

“The white man subsequently committed grand theft, while the Black woman did not re-offend. So overall, the predictions failed differently for white and Black defendants. White people were more likely to be labeled low risk yet re-offend, what statisticians might call a false negative, while Black people were more likely to be labeled a higher risk but not re-offend; we'd call that a false positive,” McNamara said.

In her courses, McNamara said she encourages students to identify and push against biases when they perpetuate inequity. Technology moves so quickly, she said, the law often struggles to keep pace.

“People are sometimes surprised when they come into my statistics class that we end up talking about things like race and class because they think of statistics as neutral, but because data is about humans, it encodes all our biases and proclivities,” McNamara said.

The solutions aren’t simple, she said, who added that more regulations around the use of algorithms and transparency about how the algorithms are making their decisions is critical.

She encourages people to urge their state representatives to introduce laws, look for experts doing work to ensure ethics and fairness in data signs and support independent journalists working to hold the humans accountable, saying it can help society from holding the same biases as it has in the past as it embraces this technology.

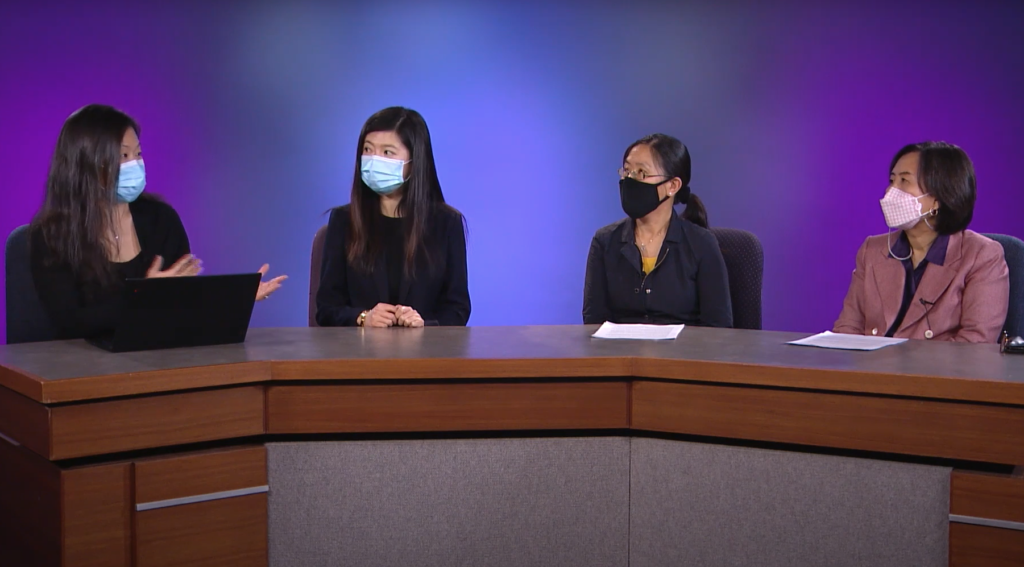

Hosted by the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of St. Thomas, Teach-in Tuesday aims to provide a space for meaningful learning and discussion around issues that impact our community. The series leverages the expertise of College of Arts and Sciences faculty to present on and invite discussion of important and urgent themes of the day.

Production for Teach-in Tuesdays is run by St. Thomas students. Emerging Media Department students receive hands-on learning on-camera and in-studio production, lighting, video and operating studio equipment and postproduction.

Explore More Teach-in Tuesday Topics

Professors Raise Awareness of Bias Against Asian Americans

Five Observations

Truth Telling and Indian Boarding Schools

St. Thomas 2025 - Foster Belonging and Dismantle Racism

Documenting Street Art, St. Thomas Researchers Better Understand Crisis

Action Plan to Combat Racism