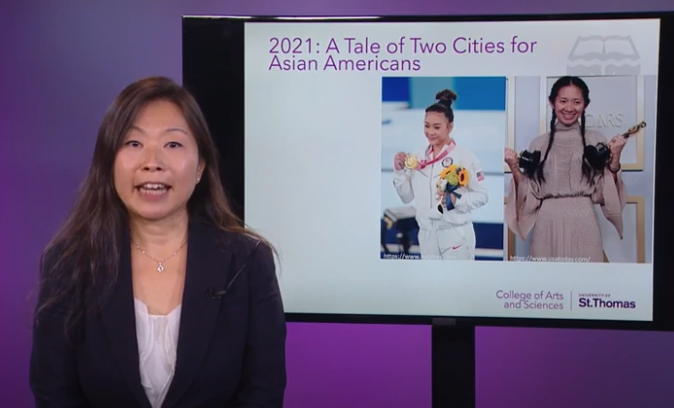

The year 2021 marked extraordinary milestones for Asians and Asian Americans. There is Vice President Kamala Harris, the first South Asian, first Black person and first woman to ever hold this position. Chloe Zhao, a Chinese national, became the first woman of color to win the Academy Award for best director. Suni Lee, a St. Paul native, was the first Hmong American gold medalist at the Summer Olympics. And Michelle Wu, a Taiwanese American, was the first person of color and first woman elected mayor of Boston.

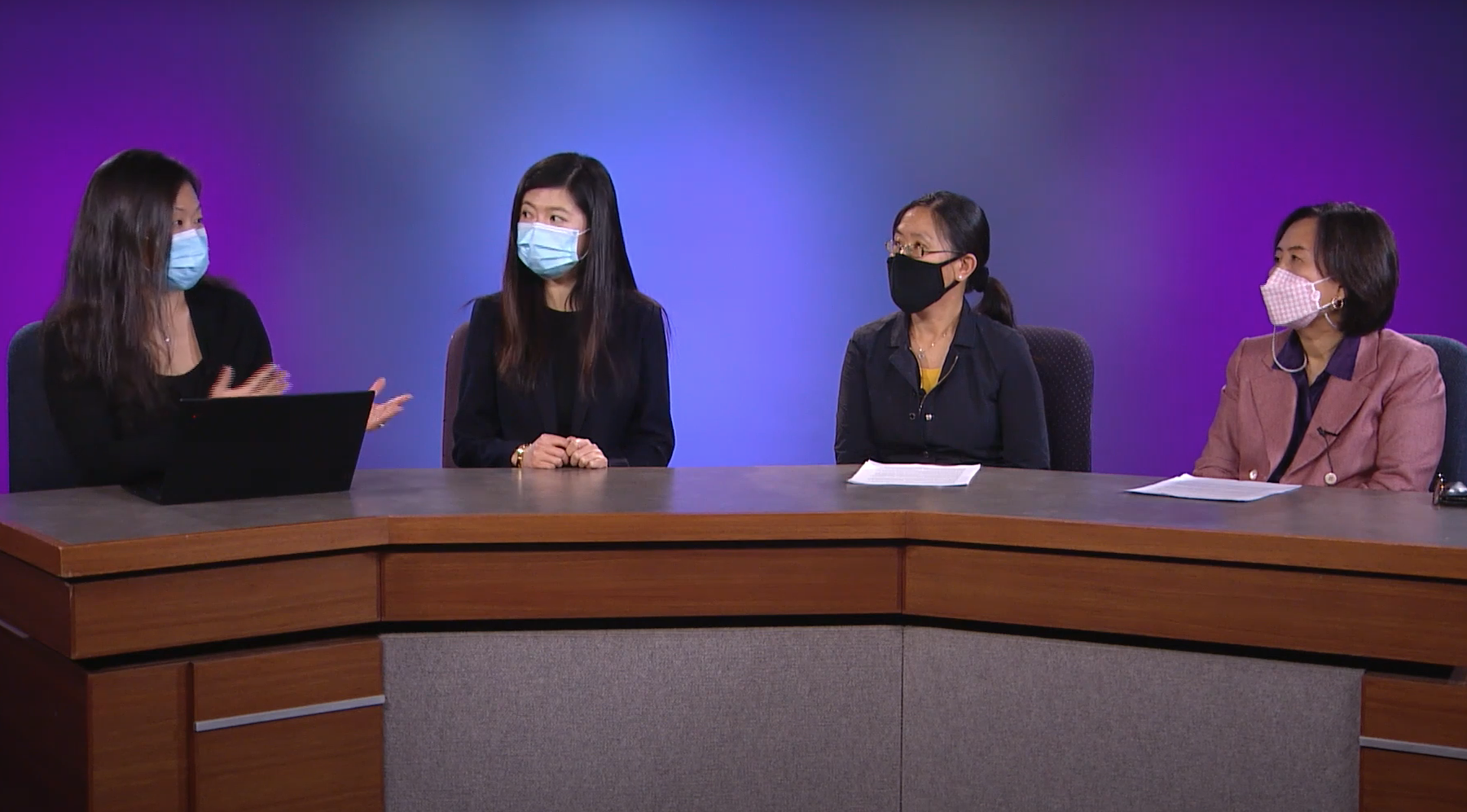

However, despite these milestones, 2021 was also a dark year for Asian Americans as there has been a rise in anti-Asian incidents since COVID-19 was first reported in China. As part of the College of Arts and Sciences Teach-in Tuesday series, Emerging Media Professor Xiaowen Guan, who is program coordinator of Strategic Communications, and Assistant Professor Monica Liu in the department of Justice and Society Studies, discussed several long-lasting and continuing racial biases against the Asian American community in an effort to bring greater awareness to the root of this discrimination. They were joined by associate professors of English Juan Li and Young-ok An for a question and answer session.

Here are five observations from their talk about the trajectory of racism against Asian Americans:

1. Since COVID-19 was first reported, people of Asian and Pacific Islander descents became a target.

Between March 2020 and June 2021, more than 9,000 anti-Asian incidents have been reported since the pandemic began, according to NPR.

“People of Asian and Pacific Islander descent have been targeted and treated as scapegoats solely based on their race,” Guan said.

Guan noted one of the “more telling” crimes, when a man stabbed three members of an Asian American family in Midland, Texas, in March 2020, with the attacker saying he did it because he thought they were “Chinese and infecting people with the coronavirus.”

Guan said that “the narrative that Asians are barbaric and animal eating subhuman is not new,” noting graffiti found in a New York City Korean restaurant that said “stop eating dogs” just one month after the Texas incident.

“The blame that Asian immigrants are being the cause of disease, in fact, has a historical origin of 200 years,” Guan said.

2. Before COVID-19, there was a long history of anti-Asian sentiments.

Asian immigrants, who were mostly from China, started coming to the United States in 1800.

Most of these immigrants resided in San Francisco, California, where a poster, titled “San Francisco’s Three Graces,” was published in a local magazine in 1882 showing three specters arising above the Chinatown district of the city, representing malaria, smallpox and leprosy.

This, coupled with another published caricature depicting Chinese laborers eating rats living in cramped and unsanitary conditions, “clearly demonstrated anti-Chinese immigrant sentiments.”

“Many Native-born Americans blamed the prevalence of the diseases on the immigrants themselves,” Guan said.

3. Asian Americans have always been in a “very unique position” in race and racial relations.

National discourses and conversations on race have been “largely centered and polarized by the rhetoric of black and white,” according to Li.

“The question we have to ask is, ‘How do Asian Americans fit into these conversations, and where do we stand in relation to power and oppression?’” Li said.

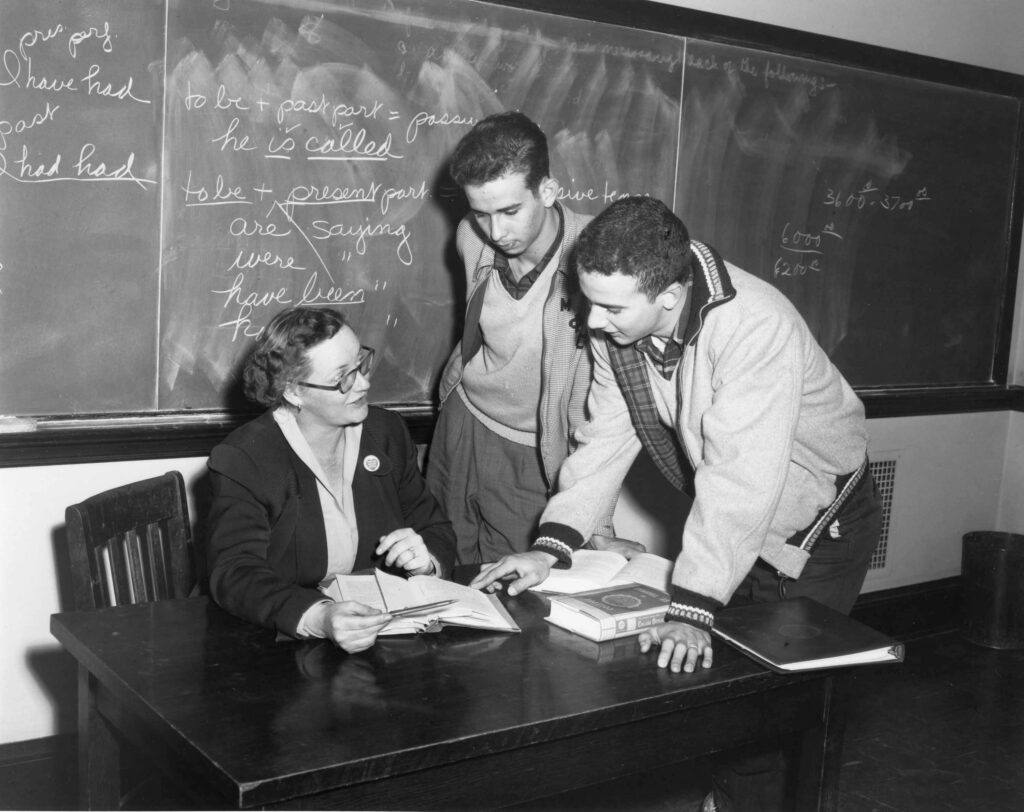

Li and Guan both spoke to how Asian American immigration history has always been situated in the context of American capitalism. For example, Guan said that the first group of Asian immigrants came to the U.S. at the beginning of 1800, recruited mostly from China to build railroads and to work on plantations. In 1875, Congress passed the Page Act, which banned Chinese women from coming to the U.S. because “they were assumed to be prostitutes and spreading diseases.”

It was 1943 before Chinese immigrants could become naturalized citizens in the United States.

“Looking at the connections between Asian American history and other history, there seems to be a potent way to approach these issues,” Li said.

4. Relations between U.S. and China have deteriorated since the COVID-19 pandemic.

Li noted a “general consensus” that the relationship between the U.S. and China has shifted “from an era of cooperation or engagement to an era of competition and confrontation.”

“This can be very difficult for China, Asian Americans and especially Chinese-Americans who may be caught in a terrible position in this competition between the U.S. and China,” Li said.

Concerns with China include national security, trade secrets or intellectual properties. Some may be legitimate, Li said, but some of these concerns also has existed before.

“Some of these concerns are also part of the same thing as the 19th-century view of Chinese immigrants as yellow perils,” Li said. “For example, seeing Chinese immigrants as posing danger or threats to social order in the United States.”

5. Some negative views of Asians were exacerbated by rhetoric and word choice.

There were terms such as “China virus” being used to describe the coronavirus that resulted in inciting a view that Chinese immigrants or Chinese-Americans were responsible for the spread of COVID-19, according to Li.

“That is kind of the contemporary equivalent of the 19th-century yellow peril, which sees Chinese immigrants as unwelcome aliens or foreigners,” Li said.

Li says the relationship between the U.S. and China “is going to continue to be challenging” and that these stereotypes “are not going to go away soon.”

“This can have repercussions to Chinese-Americans who try to balance the professional life and career in the U.S. with their personal professional connections in China,” Li said.