On a brilliant January morning, I am leading a small group of students onto a frozen lake in the middle of a Nevada mountain valley. We are pulling two boats full of gear with us. Although I have led expeditions like this many times before, this situation is different. The lake is only partly frozen, and we all know it. The ice is visibly thin, and we are going against our hard-wired northern instincts by walking on it. As we move forward, we all sense the ice beginning to fail under our collective weight. In a few steps the cracks quickly grow, and our legs crash through the ice and into the lake water below. Soon we have created a channel full of inch-thick ice floes that collide with our shins as we progress toward open water. The water is cold and the going is slow, but our spirits are high and we enjoy the feeling of the unknown that accompanies an adventure.

The lake is in arid southern Nevada and it is very shallow – not more than a foot deep anywhere – and we are all safely clad in chest waders. The only conceivable threat to us is getting stuck in the mud. My students and I will eventually reach open water and achieve our objective: the collection of a lake sediment sample. Our work here in the shallow lakes of the Pahranagat National Wildlife Refuge is part of an ongoing research project for Regional Geology and Field Methods in the American Southwest, a January Term course taught by faculty colleagues in the Geology Department.

On this morning, the ice was a surprise, but the students were undeterred. On a nearby lake, another instructor and set of students use kayaks and their paddles to break the ice and form a long pathway extending from the shore to work into the lake to obtain samples. Meanwhile, two other student groups will document and sample soils on dry land and investigate remnants of a lake that dried up nearly 75 years ago during the Dust Bowl years of severe drought. Faculty and students will closely inspect all of these samples on our return to campus, and use the results to understand the history of the Southwest and a series of lakes that existed more than 10 million years ago to the south of this area.

Wading through ice to sample lake sediment is one of many memorable episodes from my eighth and most recent January in the desert as a co-director and instructor of this course. Over these years, many students, my co-instructors and I have mapped out the geology of canyon walls, mountains and desert floors. We have hiked across major geological boundaries, examined evidence for a global glaciation, and reconstructed past events from our observations at roadside rock exposures and shallow lakes. Nearly all of this work has occurred in the midst of unforgettable scenery, such as the fiery red Aztec Sandstone near Lake Mead or the river-carved canyon lands of Zion National Park.

Students and instructor Dylan Blumentritt explore and map the smooth walls of Death Valley’s Mosaic Canyon. (Photo by Crystal Pomerleau.)

If you ask geologists about a formative experience in their education, you are likely to get at least one story about their time in a field geology course or more simply "field camp." In field camp, students quickly learn the difference between the neatly drafted and easily distinguishable geological features of their textbooks and the more nuanced and complicated reality waiting for them on an outcrop. Good field programs are far from being a simple exercise in "geo-tourism." They challenge students to make detailed observations and then piece together a story from available evidence. Our course is a three-week field experience that takes students from the complex geology surrounding Las Vegas to the desert features of Death Valley National Park. For the students, this is a unique and intense experience where new intellectual interests are formed and friendships grow. With few exceptions, they love this course.

Our course was developed and first run in January 2001 by St. Thomas geology professors Lisa Lamb and Tom Hickson, who recognized the importance of good field skills for all geology students and saw the opportunity to involve students in their own research. The course has been run each January since then. While some field camps lodge their students in an established field station, this course from the start was designed to have students camping out under the stars. As former summer camp directors, professors Lamb and Hickson instituted a number of successful routines that continue to be used in our course, such as the use of small student-led food groups that alternate planning and preparing meals for the whole group in camp. Another routine is "the big grocery shop," in which we all arrive at a supermarket, and students participate in the biggest shopping spree they have ever taken part in, buying a week’s worth of food for 20 or more students and instructors.

Because they are camping and working outdoors, the students are always especially interested in the weather. January in the Southwest is less painful than January in Minnesota, but this is not as advantageous as one might think. The desert experiences a much larger daily temperature range than we are used to, and it is not unusual to rise in the morning in chilly mid-30 degree weather and to then progressively shed layers of clothing as temperatures climb into the mid-60s or even low 70s by midafternoon. We also have had our share of wacky weather over the years. J-Term 2010 occurred during an El Niño event that resulted in flooding, road washouts and a temporary lake in Death Valley. Our most recent course, in J-Term 2013, was characterized by unusually cold temperatures, with nightly lows in the teens that made things feel a little too much like Minnesota.

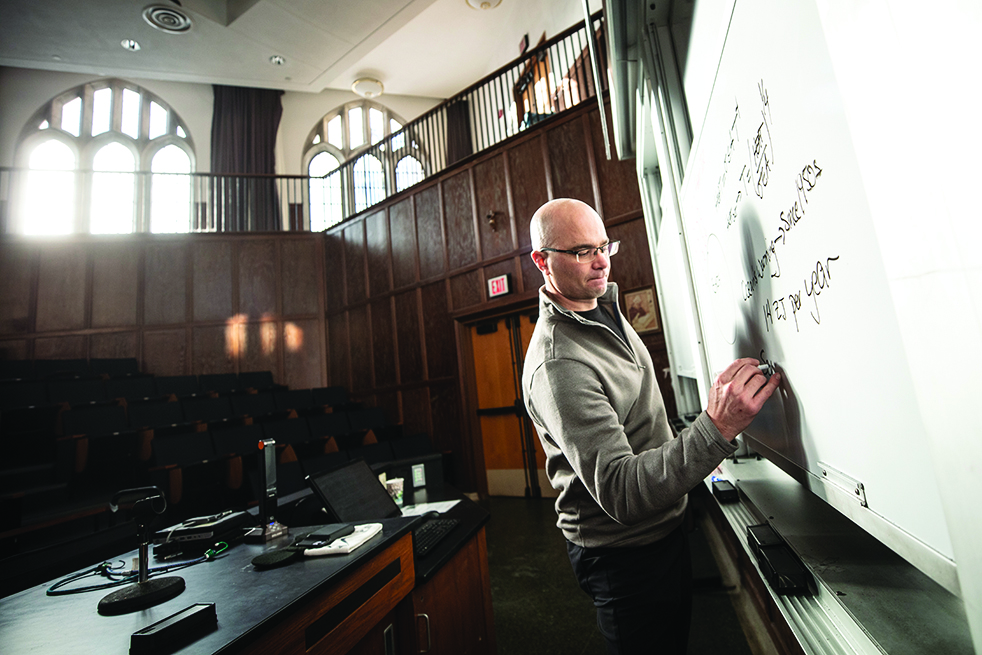

Building Field Skills

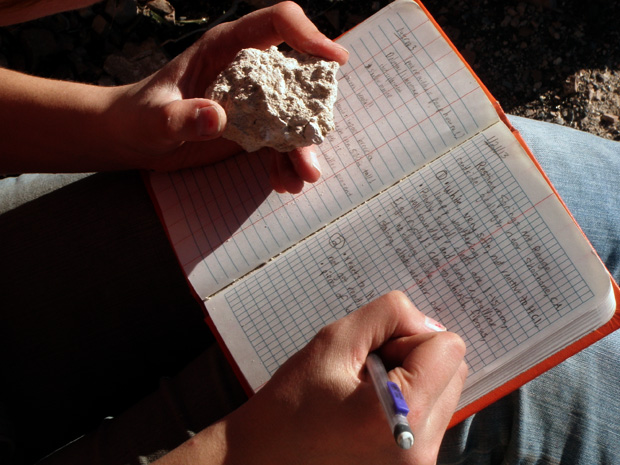

We stress two essential skills in the field: making good observations and recording those observations as detailed notes. Before they leave campus, students are given a field notebook and instructed to record everything. Along with rock hammers and compasses, these bright orange field notebooks are a nearly constant sight throughout the students’ time in field camp. Typical student notebooks will include descriptions of specific characteristics of the rocks and other earth materials they work with, sketches and labeled diagrams of rock layers and their relationships to each other, and a number of different measurements, including the orientations and thicknesses of rock layers and the precise locations where the work has been done. Students record their thoughts about what they’re observing, and some even treat their notebooks as a sort of diary, jotting down the events of the day or goofy quotes from their professor.

A student notes observations on a sample taken at a roadcut as part of an exercise near Death Valley National Park. (Photo by Kevin Theissen)

Students face new challenges in this course, and a lot of those challenges come on the first mapping project in the small area of the Lake Mead National Recreation Area known as the Bitter Spring Quadrangle – or simply, the BSQ. An immediate concern is location. Imagine that you were driven to an unknown destination armed only with a local map, then asked to take stock of your surroundings and to mark your precise location on it. In the city it is easy to use street signs and other identifiable landmarks to do this. Not so in an undeveloped desert landscape. Students must learn to read other "signs," such as the appearance of nearby landforms and their distances, and they must be able to "read" these features on a topographical map to continually track their progress through the field area. A bigger challenge for students is penciling in the first few geological features on their maps after an introduction to the BSQ and a little practice. Students have many questions as they make these first marks on their maps, but they all boil down to one big one: How well does what I have drawn on my map conform to reality?

Students do not simply complete canned exercises with known answers in this course; rather, they contribute to ongoing research projects designed by geology faculty in which outcomes are uncertain and discoveries are yet to be made. My colleagues, professors Lamb and Hickson, have been completing a highly detailed geologic map and reconstructing the geologic history of a large part of the Lake Mead National Recreation Area with student contributions over the full life of this course. I have led another project that explored the evidence for large changes in ocean chemistry at the end of one of several ancient "Snowball Earth" global ice ages. Work on lakes in the Pahranagat Valley, described at the start of this article, is part of a more recent collaboration among Lamb, Hickson and me. These projects have resulted in numerous student-faculty conference presentations, as well as published research papers with student authors.

Seeing the Scope of Earth History

Students cannot complete our course without developing a greater appreciation for the incredible range of events that have shaped our planet’s history and how long and diverse that history is. On one of the last days of the course, I often take the students on a hike in the Grapevine Mountains near the eastern boundary of Death Valley National Park. The hike is steep and requires plenty of water stops on the climb to our destination. I know we have reached it when we cross the second of two distinctive barrier-forming limestone ridges. Here, in a sequence of ancient mud stones, students can find the markings of simple worm-like creatures that once burrowed through the mud more than 540 million years ago. The markings, which look something like strands of braided rope, give evidence of a life form that had just enough intelligence to be able to move in a wide variety of directions – something that had not been achieved before and evidence for which cannot be found in the older rocks below us.

From this same spot, the view out north into Death Valley is spectacular. Gazing at the huge salt flat below with bathtublike mountain walls on all sides, the students and I can almost imagine the truly great lake that once filled much of the valley during the last glaciation. We find it much harder, however, to visualize the infinitely slow changes occurring in the Earth’s crust that have stretched and tilted the rocks around us on such a massive scale to form this great valley. This view inspires us to try anyway. The students enjoy the view, take pictures, gulp down some water, and ready themselves for the hike back to our vans. We know that out in the valley and tucked away in the many canyons that feed into it are many more stories of earth history waiting to be explored.

Read more from CAS Spotlight.