When Earth Day was first celebrated in 1970, more than 10,000 U.S. elementary and secondary schools took part. Schoolteachers across the country engaged their pupils in activities designed to draw attention to the environment and its conservation, andenvironment sections became a regular part of many elementary school science courses.

In my own fifth-grade class, Mrs. Douglas organized a contest to see who could create the best poster promoting conservation, protection and recycling. Shockingly – given the limited nature of my artistic abilities – I won with my multicolored “Keep on recyclin’” poster. The poster hung on the classroom wall for a month, then on my refrigerator at home for a week or so, then disappeared, along with any inclinationI had to recycle for the next decade or so.

While I was blithely wearing man-made fabrics, burning fossil fuels, writing reams of term papers and using products encased in plastic packaging, the earth’s temperature increased between .22 and .4 degrees Fahrenheit, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. This increase was due, the panel contends, to increasing greenhouse gas concentrations resulting from human activity, including fossil fuel burning and deforestation.

This realization, and a mounting global awareness of the limited nature of the world’s resources, led to the formation of an international environmental treaty, the Kyoto Protocol. Named for the city in Japan where it was negotiated in 1997, the Kyoto Protocol went into effect in February 2005. Its goal is the “stabilization and reconstruction of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system,”according to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. As of this year, 183 countries have ratified the agreement. Notable exceptions include theUnited States.

Industrialized nations that have ratified the protocol have agreed to reduce their collective greenhouse gas emissions by 5.2 percent from the level established in 1990.Nonindustrialized nations – those with developing economies such as China and India – are not bound to reduce emissions, but have agreed in principle to do so. To do this, the treaty allows what are called “flexible mechanisms,” such as emissions trading, which allow countries to meet their emissions limitations.

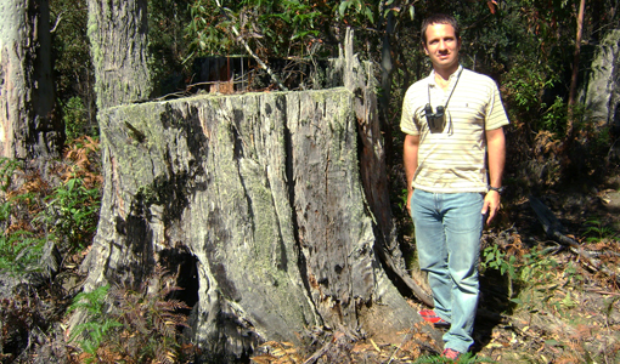

Since the treaty went into effect in 2005, a new type of commodities trader has been born, one involved in the practice of “cap and trade.” Among these new ventures is Forest Carbon Offsets, LLC. Gabriel Thoumi ’02 M.I.M., a consultant for the global firm, is not only a financial pro, but also a passionate environmentalist who is determined to reverse climate change.

The cap-and-trade marketThoumi is a project developer for Forest Carbon Offsets, a global forestry carbon-project development firm. He also is a frequent participant in global consensus projects with The Forests Dialogue and helped write the forestry section of the American Clean Energy and Security Act of 2009. He has coauthored a landmark financial analysis for the United Nations’ Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Developing Countries (REDD) program that will guide stakeholder discussions at the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen in December. With Talitha Haller, Thoumi also wrote a first-of-its-kind financial analysis of forestry carbon offsets, analyzing them using Generally Accepted Accounting Principles.

Cap and trade is a program or policy that places a mandatory cap on emissions while providing organizations – and nations – with flexibility in how they comply with these regulations. Entities can, for example, “sell” their leftover allowances to an entity that is likely to exceed its cap.

Before founding Forest Carbon Offsets, Thoumi was global forestry director and senior business development manager at MGM International, a subsidiary of Morgan Stanley, where he was involved in developing forestry carbon-offset projects. By combining his passion for conservation with his business acumen, Thoumi has built a successful career in the business of cap and trade.

Cap and trade is a program or policy that places a mandatory cap on emissions while providing organizations – and nations – with flexibility in how they comply with these regulations. Entities can, for example, “sell” their leftover allowances to an entity that is likely to exceed its cap. Successful cap and trade programs purport to reward innovation, efficiency and early action, and provide strict environmental accountability without inhibiting economic growth.

The United States’ Acid Rain Program is one example of this success. It has reduced sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides in the atmosphere, resulting in a reduction in acid rain.

“Over the last four years,” Thoumi says, “I have observed the impact of global climatic disruption while working with public and private sector teams. I have seen decimated lands in Borneo that were once a rain forest. I have experienced the rising sea flooding Jakarta when I lived there. And I have witnessed the results of drought-induced hunger. Because climate change is very real to me, and a matter of personal and globalinterest, I decided to use my business background to help.”

Thoumi’s company is involved in developing international financial instruments based on the natural capacity of carbon dioxide (CO2) sequestration within trees. These instruments then are sold to utilities, corporations and funds within either voluntary or compliance cap-and-trade programs globally.

For reference, last year the global forestry carbon market was roughly 12 million tons of CO2-equivalent (CO2e) and it sold for about $45 million.(1) Forest Carbon Offsets pays commercial and community interests to properly steward their ecosystems. In other words, in carbon markets, businesses must either reduce their pollution levels or pay another business – one better at lowering greenhouse gas emissions – for its“unused” emissions. Under the American Clean Energy and Security Act of 2009, the global voluntary offset market could grow from roughly 123 million tons of CO2 in 2008 to 2 billion of tons of CO2e by 2014.

According to Thoumi, we are all “stewards of the Earth’s resources for future generations.We must engage stakeholders and encourage them to develop sustainability initiatives within their spheres of influence. Of primary concern are the tropical forests that currently are being deforested at an annual rate of 13 million hectares. The deforestation practice in this area is responsible for roughly 20 percent of all global greenhouse emissions.(2)

“Basic biology informs us that trees and plants absorb carbon dioxide and produce water,” Thoumi says. “The loss of this flora in the tropics has had a significant negative impact on the quality of environmental services such as water purification, pollination, soil quality, water storage and rainfall, fisheries, biodiversity, carbon sequestration and food production provided by a properly stewarded ecosystem.”

Cap and trade in actionIn essence, when an entity purchases an offset, it is funding a project that will reduce greenhouse gases, or in the case of Forest Carbon Offsets’ clients, limit deforestation. The forestry offsets can be banked and sold later by the buyer or used to settle on a compliance or pre-compliance emissions obligation.

On a smaller scale, individuals and businesses have entered the offset market. Through an organization such as Carbonfund.org, for example, I can donate funds to offset thegreenhouse gases I produce as a typical consumer. My donation funds projects that have been verified by a third party – projects such as the creation of a wind farm. The credits created by this project are then retired, resulting in a net “loss” of CO2e in the world. Companies such as Dell, Motorola, JetBlue and Amtrak have voluntarily committed to reducing their emissions by taking part in the funding of such offset projects.

Forestry carbon sales are also occurring on a large scale:

Pacific Gas and Electric purchased 600,000 tons of CO2e for $9.71 per ton or a total sale of nearly $6 million as part of the Climate Action Reserve.(3)

The Norwegian government purchased 520,000 tons for roughly $14 per ton for a total sale of $7.3 million as part of the New Zealand Permanent Forest Sink Initiative.(4)

The Ibi Bateke Carbon Sink Plantation Project sold 500,000 tons CO2e to the World Bank Bio Carbon Fund.(5)

The dissentersOne of the fundamental issues concerning trade in offsets is their value. Who determines the market price of a carbon offset? In most cases, an independent party not connected with the proposed project is used to establish the base price of anoffset and establish that the credits generated are compliant with the Kyoto Protocol. While several standards for certification exist, no one standard governs the practice. This leads to the problem of exaggerated CO2e claims.

Kyoto has established Clean Development Mechanisms (CDM) that allow industrialized nations with a reduction commitment to invest in projects in developing countries that will reduce emissions there. This is an alternative to projects that would be more expensive in their own countries – thus, the investment by the Norwegian government in a project in New Zealand noted above. Yet critics of cap and trade or emissionsoffsets take issue with these mechanisms on several fronts. An argument has been made that this practice actually provides a financial incentive for entities to pollute more so that, later, they can reduce their emissions from a fictional baseline and earn emissions credits.

More widespread is the criticism that carbon-offset projects either have a negative impact on an area’s environment or its people. Projects aimed at reducing deforestation, for example, can take away the livelihood of an indigenous populationwho relied upon the sale of lumber or the cleared land to earn an income.

Finally, there is the financial impact of the cap-and-trade practice. Dr. Dave Vang, professor and chair of the Finance Department in the Opus College of Business, states, “If the United States abides by all restrictions and bears all the costs placed on our economy, it will be for absolutely nothing if other countries like China and India refuse to participate.…If other countries do not cut back on carbon production…we asa nation might find that we would have been better off if we hadn’t wasted trillions of dollars on cap and trade and, instead, we used those resources to adapt the citizens of our country to a higher temperature environment.” This imbalance in requirements is the primary reason the United States has said it would not ratify the Kyoto Protocol.

Vang also thinks that cap-and-trade requirements could provide a political incentive for trade protectionism. As American industries downsize to comply with emissionrestrictions, consumer costs and unemployment increase, he theorizes. “Imagine that our trade partners do not comply with global warming initiatives … now try to imagine the pressure that will be put on our political leaders who will be bombarded with requests for import tariffs and quotas directed against our trading partners that chose to not follow the same rules we do. The trade war triggered by the Smoot-Hawley Actplunged the world into an even worse economic tailspin in the 1930s.”

Looking forwardFor Thoumi, opponents of cap-and-trade practices are shortsighted and do not understand the real crisis. “Climate change is a reality,” he says. “And while the causes of this change can be debated, there is little doubt that the Earth’s mean temperature has increased during the last 150 years.This critical transformation is one reason why scientists such as Dr. John Holdren, co-chair of the President’s Council of Advisers on Science and Technology, prefers to describe the change in more dramatic terms – global climate disruption.” (6)

This sense of urgency has led Thoumi and his partners to become involved in a project in central Kalimantan, Indonesia. For years, companies have burned forests in this area to clear the land for palm-oil plantations. Unfortunately, the land beneath the trees is peat, which can burn underground for months at a time, creating a haze of black smoke. In addition, both illegal and legal logging have contributed to the deforestation of the area. Indonesia has 120 million hectares of forest and peat land, of which 28.3 million have been cleared or degraded, according to the Forestry Ministry.

The project on which Thoumi is working to restore the forests in this region is called the Katingan Peat Conservation Project. The land here is estimated to store about one million tons of carbon. Project members plan to sell this carbon to the voluntary carbon markets, which are worth about $2 billion per year. Money from the sale of carbon credits will be used to restore degraded land within the conservation area, developnew jobs for the residents of the region, and restore about 600,000 acres of orangutan habitat. This last feature may be the most important outcome. For while it may be difficult for the average person to understand carbon offsets, cap-and-tradepolicies or the complex financial instruments involved in buying and selling offsets, saving an orangutan is something we can all relate to. Perhaps this school year, a young fifth-grader can create a poster advocating for the restoration of orangutanhabitats. It just might win.

(1) Hamilton, Kate, Milo Sjardin, Allison Shapiro, and Thomas Marcello. Fortifying the Foundation: State of the Voluntary Carbon Markets 2009. Free online at www.ecosystemmarketplace.com.(2) Gullison et al. 2007. Tropical forests and climate policy. Science (May 10).(3) https://lakeconews.com/content/view/9650/773/(4) https://www.carbon-financeoline.com/index.cfm?section= asiapacific&action=view&id =12291(5) https://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/ EXTERNAL/NEWS/0,,contentMDK: 22266192~menuPK:34463~pagePK:34370~piPK:34424~theSitePK:4607,00.html(6) https://www.climatesciencewatch.org/ index.php/csw/details/holdren_global_climate_disruption/