One in four Minnesotans has a criminal record. It’s a record that employers, landlords, legislators and licensing boards use to shape policy and determine the character of an individual. It’s an indelible mark that disproportionately impacts poor and nonwhite Minnesotans. But how useful is it?

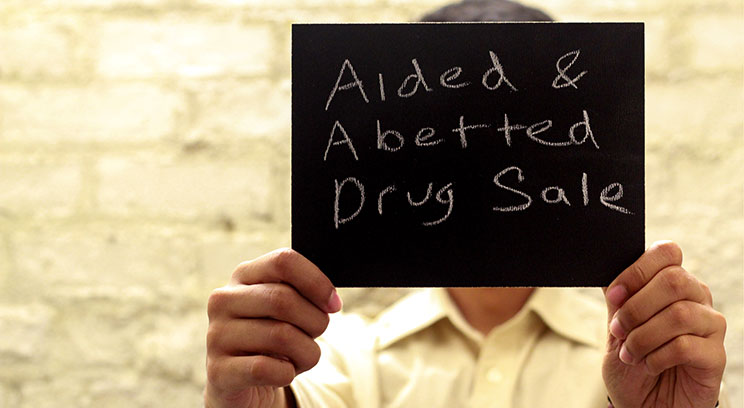

A little over a year ago, I started collecting stories from what I call the other 75 percent: people who have criminal histories but no record. That is, people who have gotten away with crimes. Some participants were gleeful, some embarrassed and some deeply haunted by guilt over what they had done. But all (200 and counting) share one thing in common: none was caught.

The stories are part of a project called We Are All Criminals, and can be found on a website and as part of a traveling exhibit. We Are All Criminals seeks to remind viewers that while we have all transgressed, we are also all human and may be in need of compassion, forgiveness and a second chance.

The stories are humorous, humiliating and humbling, in turn.

Take the woman who, at age 16, took a summer chemistry experiment too far, destroying a state park toilet with a homemade explosive; she’s now a pediatrician, a profession from which she would have been barred had she been caught.

Or the man who used his federal aid to finance collegiate drug runs; he’s now an attorney, building a nonprofit.

Or the teacher who would drink to oblivion and somehow drive the long route home, the social worker who assaulted a classmate out of spite, or the retiree who greased up St. Paul’s trolley tracks with stolen lard just to vex the operator.

Each life course would have been altered significantly had the participants been defined by their worst act. If each job, housing, college and loan application required disclosure of the offense and each background check relayed the record as a marker of the applicant’s true character. Instead, the participants were defined by their accomplishments rather than their crimes.

In Minnesota, we’ve created a state of perpetual penalty, where the punishment begins when the sentence ends: Legislative sessions see calls for more broad and stringent collateral sanctions to records, employers adopt blanket bans on hiring former offenders, and our judiciary has found that what remedies to the problem exist are illusory in practice.

Too many people currently are prohibited from reaching their full potential. We must create a road to redemption for our neighbors, friends, colleagues and strangers. The first step in doing so is recognizing that we’re not all that different.

We can take Pope Francis’ lead: There were reports that upon visiting the Regina Coeli prison in Rome, the pope confided in the inmates that he had stolen an apple from the neighbor’s orchard as a child. He wept, stating that he too was a criminal.

Read more stories at: www.weareallcriminals.com.

About the Author: Emily Baxter is the director of Public Policy at the Council on Crime

and Justice, a Bush Fellow and a Robina Institute Fellow. She recently represented a man who lost his job after he stole a sandwich from a grocery store. Unless the law changes, his legal options for a second chance have run out.

Read more from St. Thomas Lawyer.