Excerpt from Logos: A Journal of Catholic Thought and Culture 27, no. 4 (Fall 2024)

I once asked a colleague whether he loved his students. “I love them like I love my enemies,” he replied. That was meant as a joke, of course, but there was also something sincere about his reply. For Christians really are called to love their enemies (Mt 5:44). But what does it mean to love? How can one love one’s students in an appropriate way?

According to St. Thomas Aquinas, love has two key components: one must desire the good of the other and one must desire union with the other (Summa theologiae II–II, q. 27, a. 2). A love lacking in one or both desires is either a severely deficient love or no love at all.

Importantly, to really love another person I must desire some good for the person for his or her own sake. I can’t be thinking about what’s in it for me.

To desire union with another is to desire to be united or joined to him or her in some particular way and need not – and in many cases absolutely should not – involve physical proximity or contact. As Aquinas explains, one person can be united to another in intellect by coming to learn or contemplate the same truth, or in will by coming to love what he or she loves or to share some of the same goals (See Summa theologiae I–II, q. 28, a. 2). When that love is reciprocated, a friendship is formed. And when it is made a habit, it becomes a virtue.

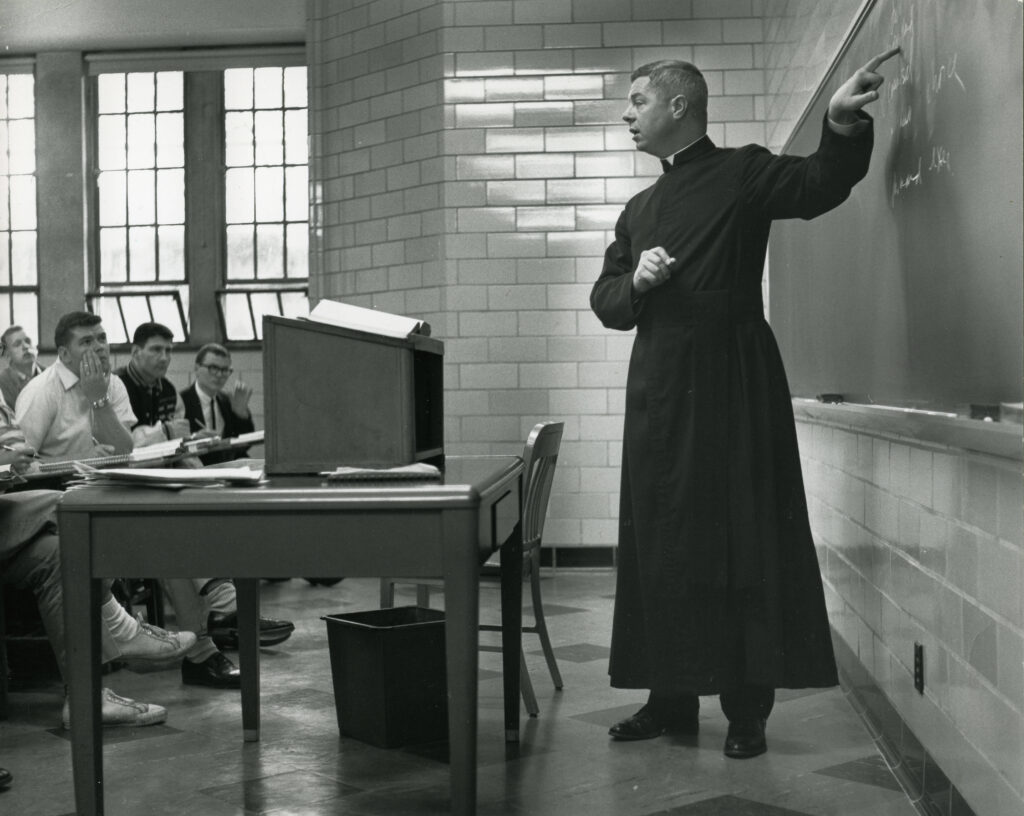

We teachers have an obligation to love our students, not only from the universal obligation to love everyone, or even from the contractual obligations teachers accept, but from a special obligation we have to those individuals who have been placed in our care.

And, indeed, for that reason we have an obligation to love all of them and – even more than that – we have an obligation to love each of them. This requires, I think, knowing each by name, knowing their relevant strengths and struggles, and knowing enough of each student’s story to be able to tailor feedback, recommendations, and accommodations. I need to know my students well enough to know whether they are in need of scolding and stern advice or support and encouragement.

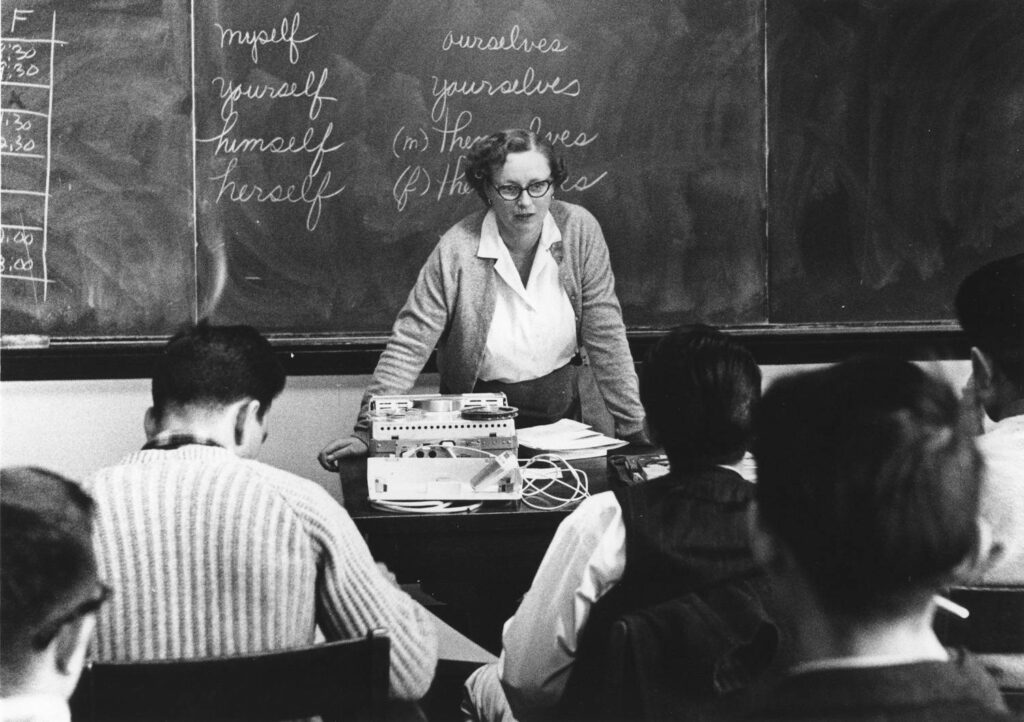

Preserving a healthy, professional and fruitful relationship with one’s students is a delicate matter. I often find myself reminding them that I am neither their therapist, priest, parent, nor peer. I am their teacher, and it belongs to my office to desire for them the primary goods of knowledge, wisdom, understanding, and the habits of mind that facilitate the apprehension of those goods (though I am happy to direct my students to other trusted resources). I think that it is when the teacher or the student (or both) fail to remember their proper offices, and the proper goods and forms of union that are appropriate to those offices, that inappropriate attachments develop. But our response to these hazards should not be to refrain from loving our students. Our response should be to work toward a better understanding of why we should love our students and what form that love should take.

This story is featured in the winter 2025 issue of Lumen.