Foreword by Dr. Robert Kennedy

Alumni profiles by Kate Norlander and Kelsey Wanless ’11

In his 1961 encyclical, Mater et Magistra, Pope St. John XXIII offered what is now considered the classic definition of common good. He said that the common good is “the sum total of those conditions of social living whereby men are enabled more fully and more readily to achieve their own perfection.”

This spring, St. Thomas made public its new branding identity, which focuses on an explicit affirmation of the university’s commitment to serve the common good. This is a noble commitment and certainly one that is deeply embedded in the Catholic tradition. It is also true that the phrase “common good” is one of the most ambiguous terms in social ethics.

In Pope St. John’s definition, the common good is not so much a goal to be pursued as it is a means to an end. Like any other means, it only can be properly understood, and we can only evaluate concrete examples, by referring to the end. And this is where much of the ambiguity lies. Even if different groups agree that the common good of society is instrumental, it takes on a different character when there are disagreements about the nature of the human person and the life well lived.

The Catholic tradition, though, has its own profound convictions about the nature of the human person and a good human life. Broadly speaking, these convictions focus on two levels: a good life here and now, as well as the recognition of the transcendent destiny to which all persons are called.

The common good of a society, then, must first support the flourishing of human persons in their earthly lives. Pope Paul VI spoke of this as integral human development – a theme that has been emphasized by all recent popes and is understood as the development of the whole person, not merely material or economic progress (as important as these are). He also insisted that the common good is never fully established unless every person in the community is enabled to flourish.

The very idea of human flourishing in the Catholic tradition rests on a deeper conviction about human nature. That is, because we all share a common human nature, there is something objective and true about what constitutes genuine human fulfillment. We are creatures, not creators, and we do not invent the conditions for our own happiness. And so the Catholic tradition rejects a Libertarian notion that claims that the common good consists in the greatest freedom for individuals to define fulfillment for themselves. Promoting conditions that make it too easy for people to make self- destructive choices is no part of the common good.

Even so, integral human development is not the final word, for the Catholic tradition insists that we were made for something more. As images of God, that something more is a share in God’s life and this is the ultimate foundation of human dignity.

As Pope Francis reminds us frequently, the unborn, the elderly, the poorest and most wretched person in the community all share this destiny and this dignity. The common good as means to an end falls short when the weakest and most vulnerable are neglected.

Pope St. John Paul II reminded us nearly 30 years ago, in his encyclical Sollicitudo rei socialis, that solidarity is one of the most important Christian virtues. This is, he said, not merely “a feeling of vague compassion or shallow distress at the misfortunes of so many people,” but rather “a firm and persevering determination to commit oneself to the common good.” No individual or organization can do everything, but we can embrace solidarity by being mindful of the ways in which our everyday choices – our votes, our purchasing decisions, our professional activities – have an impact on the poor and vulnerable.

As St. Augustine observed: A world populated by sinful human beings will never succeed in perfecting the common good. There is always work to be done improving, defending and repairing the social conditions that enable each member of society to flourish and, ultimately, to share God’s life. This is why the virtue of solidarity is so important for Christians and why a commitment to the common good is so appropriate for a Catholic university.

A Servant Leader

It’s common for parents to say that having children changed them, but as the parent of a child with a disability, John Kelly ’11 CSMA can say that the birth of his son helped influence how he considers the common good.

Mindful of Jesus’ call to serve “the least of these,” Kelly said that his son Jack has opened his eyes to the hidden needs around him. “I might not be as generous without my son,” he said.

As senior vice president of tax at UnitedHealth Group, Kelly recognizes that understanding the hidden needs around him is not only important at home and in his community but also at work. In 2006, UnitedHealth Group received some bad press and Kelly faced his first significant challenge at the company. Instead of leaving, he was motivated to be part of the solution and helped investigate what went wrong, and was part of the team that corrected and modified the processes at issue for UnitedHealth. He also supported UnitedHealth’s effort to become a more actively socially responsible company. As a tax professional, Kelly sees his work as serving the common good by helping the company’s bottom line and, through that, its shareholders, employees and the community that they serve.

Today, he leads a department of more than 90 people on four continents. As he travels, he makes sure to meet with his team members, sometimes individually, to demonstrate their importance on his team. He also values being truthful, including during performance reviews.

“You don’t have to be mean, but you need to help someone understand if they aren’t performing well,” he said.

He hopes that, as a leader, his dedication to stewardship sets a good example for others in his organization. He and his wife have examined how they spend their time, talent and treasure in light of the catechism and

Catholic social teaching. As a result, he has been an active volunteer and generous donor to such organizations as The Arc Greater Twin Cities, Opportunity Partners, Catholic Charities and Wakota Life Care Center. He also supports Catholic education, ranging from elementary schools to St. Thomas, where he received his CSMA and now serves as an advisory board member for the Center for Catholic Studies.

He found that the education he received in the CSMA program helped frame his thinking about stewardship and his professional life.

“If you help people get a good Catholic education, they will come out with ethical thinking consistent with the church,” Kelly said. “This education won’t just generate nonprofit workers but also Catholic professors, lawyers, accountants and other professionals.”

The program also enabled him to answer spiritual questions more thoughtfully. His daughter Bridget has followed his example in pursuing an M.A. degree in Catholic studies, and he enjoys his discussions with her about the books they have read as a result of their involvement in the program.

Kelly’s grounding in the common good extends to all roles he plays as a leader, a father, a husband, a friend and a volunteer. His life models his belief: “If a leader doesn’t do the right thing, no one else will.”

A Think-and-Do Tank

You may not know her name, but you have likely heard of her work. Meg McDonnell ’07 is quickly becoming noteworthy for her work helping to re-establish the social value of connecting the importance of marriage, sex and children.

She has garnered attention for being awarded a national Robert Novak Journalism Fellowship in 2011 for her project on marriage and young adults, and she was named one of 30 Catholics Under 30 by FOCUS in 2013. Currently, she is the executive director of the Chiaroscuro Institute (CI), a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization in Washington, D.C., founded by professor Helen Alvaré of George Mason University Law School. The CI’s mission is to “relink the goods of sex, marriage and children, especially but not exclusively among disadvantaged populations, in order to promote the flourishing of adults and children and whole communities.” It was created as a response to the “demand side” of abortion – for women who find themselves in situations where abortion seems necessary.

Calling themselves a “think-and-do tank,” the CI begins with the latest research and academic work, and then acts upon it through communication, education and mobilization. The organization has two programs that attend to the various aspects of its mission, Women Speak for Themselves (WSFT) and I Believe in Love, which are girded by the same goal: empowering individuals to speak out in the ongoing discussion of sexual ethics.

WSFT tackles the issue from the vantage point of the common good instead of a liberal vs. conservative paradigm, and offers education resources that do the same. For example, one of WSFT’s issue sheets points to data indicating that countries around the world that respect religious freedom are more likely to recognize the equality of women. WSFT shares this data, along with other practical tools, with women to help them mobilize in their local communities.

I Believe in Love is an online community serving millennials who are most disproportionately impacted by the high nonmarital birthrate and high nonmarriage rate – namely, those who have graduated high school but will not graduate from a four-year college. As McDonnell explained, it “gives them a place to reflect on their lives and struggles, and allow that reflection to redirect their decisions in love, marriage and sex, particularly. Ultimately, we want to instill hope and solidarity among those who want lasting love and marriage, but are struggling to realize it.”

The CI is not a Catholic organization, nor are its programs specifically Catholic. Yet, it is imbued with an evangelical spirit that acts like the “field hospital after battle” that Pope Francis has encouraged. McDonnell referred to her work as “pre-evangelization,” or an approach that helps to soften hearts to the Catholic Church.

“What we’re trying to do is show that getting married and having children is not just a religious thing to do, but a human thing to do,” McDonnell said.

McDonnell said her time in Catholic studies helped prepare her for the work she now does.

“In a culture that can often be dismal, [my professors] instilled in me hope that the truth always prevails and gave me the language to evangelize to people of all backgrounds,” McDonnell said.

Preparing Students to Flourish

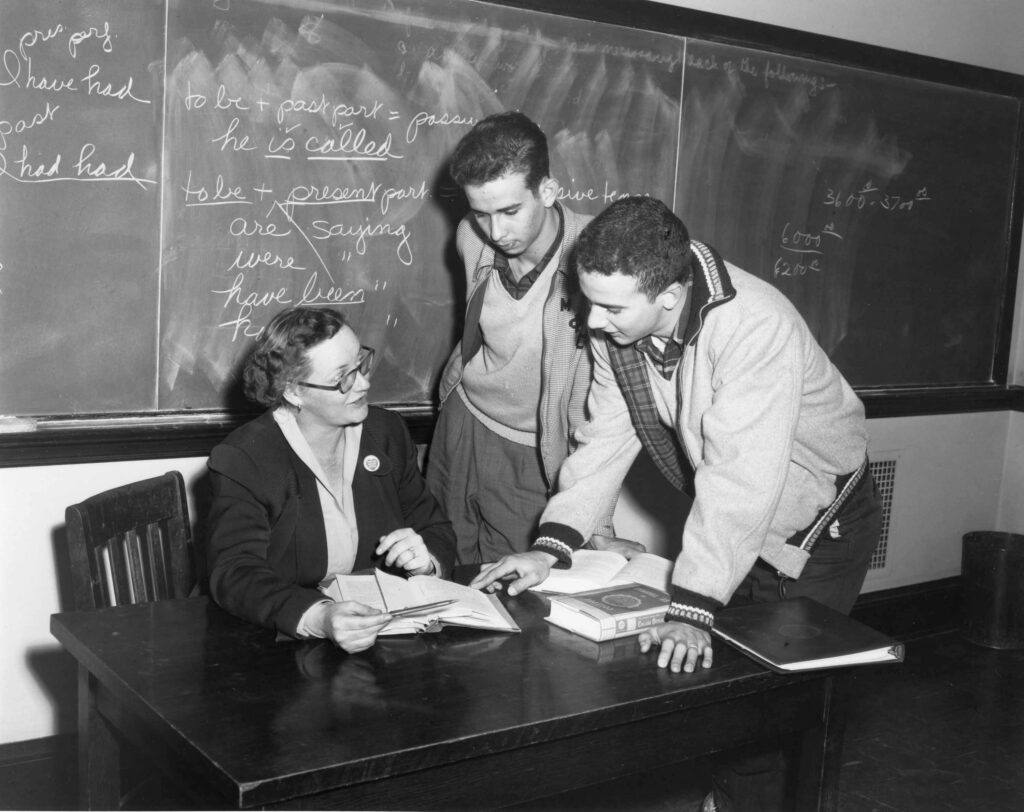

John Lane looks to a quote from G.K. Chesterton to guide his work as a high school theology teacher: “Education is simply the soul of a society as it passes from one generation to another.” At a time when education is viewed by many to be the passing on of skills to perform various tasks, Lane strives to bring education back to its traditional understanding: namely, the integral formation of the human person.

After graduating from St. Thomas in 2012 with a bachelor’s degree in Catholic studies and philosophy, Lane received his Master of Education in 2015 through Pacific Alliance for Catholic Education (PACE) from the University of Portland. Modeled after the ACE program at the University of Notre Dame, PACE comprises three components: summer coursework, intentional living in spiritual communities and teaching in underprivileged schools during the academic year.

For his PACE teaching assignment, Lane was placed at St. Joseph Catholic High School, a small school in Ogden, Utah, where he taught both literature and theology. Today, Lane is finishing his first year as a freshman theology teacher at St. Anthony’s High School in Long Island, New York, which is in a more affluent area of the country than St. Joseph. Yet, reflecting on his experience at both schools, Lane has found that the particular needs of 15-year-olds are essentially the same, regardless of poverty or wealth.

“As a theology teacher, my primary work is to make a case for the Catholic Church against the mainstream culture,” Lane said. “As an educator in general, my task is to make a claim for a liberal arts education – that is, an education that recognizes the whole human person.”

Lane said that his time in Catholic studies was deeply formational in preparing him to educate others. “My Catholic studies’ professors were the first to truly challenge me, not merely as a student, but as a human being,” Lane said.

His courses in Catholic studies gave him a fuller understanding of the nature and purpose of the human person. With such a comprehensive, well-defined understanding of the human person, Lane said, Catholic education plays a critical role in the discussion and advancement of the common good.

We cannot fully progress toward a common good if there isn’t a shared understanding, or set of defining characteristics, of the human person, Lane said.

In that light, it was easy for Lane to see that education is meant for much more than transferring just information or skills. Rather than preparing his students to simply function, Lane aims to prepare them to flourish in society, andto ready them to work for the common good.

“We are not just educating students so they can function within society, like a cog in a machine,” Lane said. “We are educating students to achieve some greater goal, a spiritual goal.”