Stumbling on Happiness, The Science of Happiness, Eight Steps to Happiness – any bookstore will show that finding happiness is a “hot” topic. But it is not a new one. In The Search for Happiness, the introductory core course for majors in Catholic Studies, students discover that Aristotle understood happiness as the impetus for all human activity. “Happiness is a perfect topic for getting at fundamental Catholic claims about what it means to be a human being and live well,” says Catholic Studies professor Deborah Ruddy, who taught the course in fall 2007.

In the course students begin by reviewing some contemporary understandings of happiness in “positive psychology” and in popular “happiness quests” focused on pleasure, professional achievement and sentimentalized human relationships. Then, turning to Scripture, particularly the character of Moses and Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount, students wrestle with the challenge of a merciful yet demanding God. Jesus’ teaching that blessedness is found among those who mourn, weep and endure persecution complicates the question of happiness. Jesus points to a world beyond this one, where perfect happiness – beatitude – can be found. But then the question arises: what are we to do here and now?

After an exploration of the stark contrast between popular and biblical notions of happiness, the course turns to literature. Leo Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Illyich depicts the unhappiness and ultimate tragedy of an unreflective life. “Students see the ‘fall’ of a life that simply falls in line with conventions,” Ruddy explains. “Ivan’s aspiration to move through life ‘easily, pleasantly, and properly’ leads to horrifying regret. On his death bed, he asks, ‘What if my entire life, my entire conscious life, simply was not the real thing?” In the end, Tolstoy’s story leads students to ask, “What is the life worth living? What can we hope for?” From this point on, the course looks at various philosophic answers to these questions.

Ruddy guides students in the reading of a classic text, Aristotle’s Nichomachean Ethics, as they examine the role of virtue, virtuous friendships and contemplation in human development. Aristotle’s virtue theory, his insight into the social nature of the human person and the teleological character of human action, and his distinction between real and apparent goods, all give students a vocabulary for talking about the good life. Having examined a reason-based account of the life worth living, the stage is then set for students to turn to Augustine’s Confessions, where the unique character of Christian happiness dramatically unfolds.

“Students relate to the restlessness of Augustine,” Ruddy observes, “and they find that they, too, deeply desire something that transcends this world.” As Augustine moves through intellectual, moral and religious conversion, the students see the continuities and discontinuities between Christianity and the Greco-Roman world emerge. For Augustine, the distinctly Christian virtue of humility shifts the quest for happiness from one of achievement and self-pride to one of gift and humility.

Shifting back to a work of the imagination, students then read C.S. Lewis’ The Great Divorce, which explores the importance of human freedom in shaping our destiny. Lewis brings to life the everyday obstacles to true happiness in God and shows how we become eternally what we give ourselves to in this life. One character, “Ikey,” is a prototypical economic libertarian who values autonomy and productivity above all. Ikey embodies many of the cultural ailments that Josef Pieper addresses in his classic work Leisure the Basis of Culture. In Pieper, students consider what makes a culture truly humanizing and conducive to true happiness. Culture, Pieper argues, depends for its very existence on leisure, which is not simply the absence of work but rather a disciplined stillness and receptivity to God. It finds its ultimate expression in cultus, worship of the divine. “Praising God,” Ruddy explains, “is at the heart of leisure.”

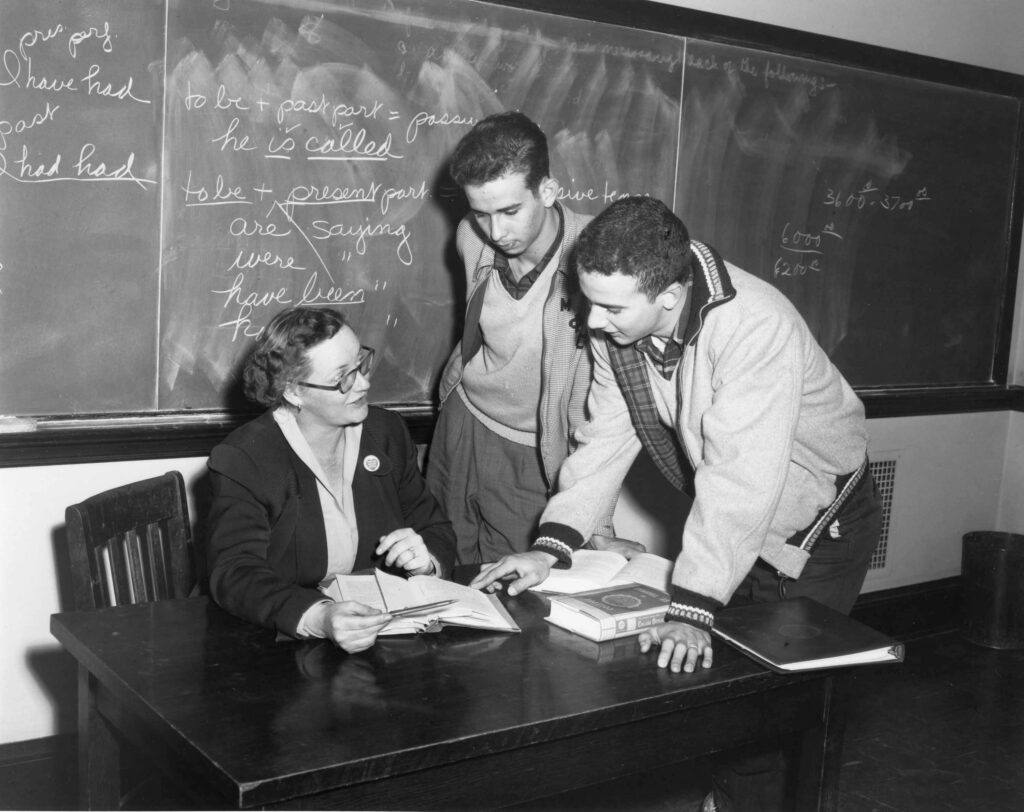

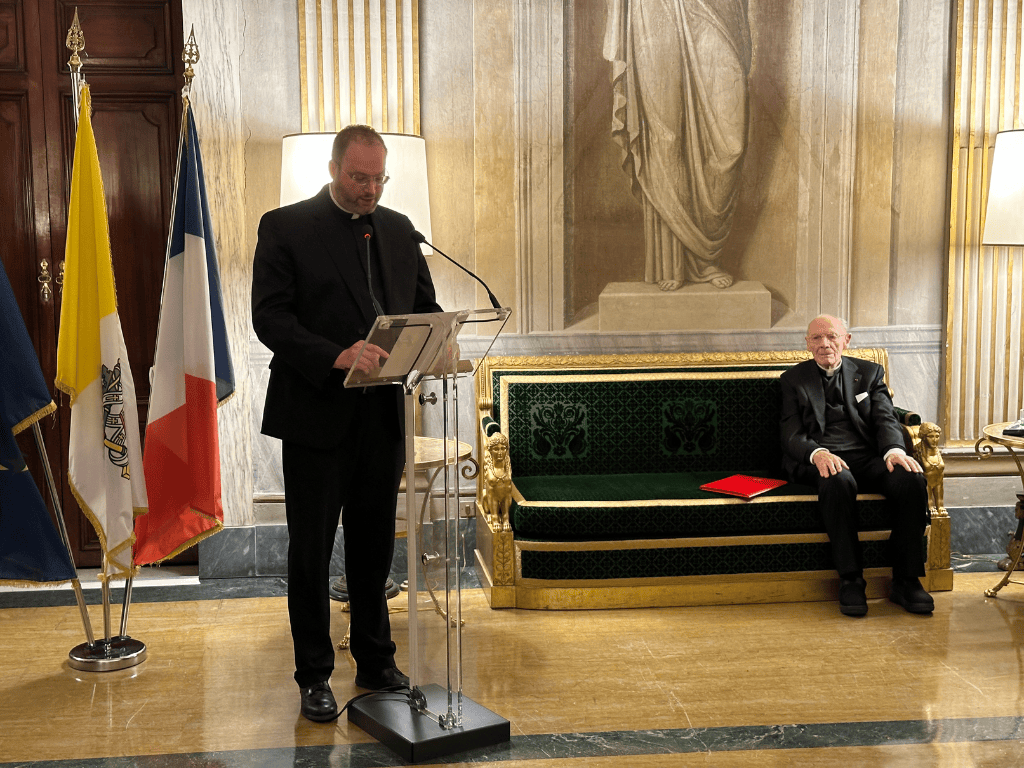

Habits of leisure or contemplation can be learned through an encounter with beauty. Catholic Studies professor Father Michael Joncas visited Ruddy’s class to give visual expression to the topic of happiness. Through a study of John Paul II’s “Letter to Artists” and various encounters with religious artwork, students learn the practices of aesthetic appreciation whereby attentive gazing allows meaning to reveal itself gradually and not always on one’s own terms.

The course concludes with a reading of Dorothy Day’s autobiography, The Long Loneliness. Immersed in the life of a modern Catholic convert, students see happiness pursued in the midst of very modern problems and questions. Day’s Augustinian searching for her own vocation led to a lived experience of the Christian paradox expressed in the beatitudes. Her self-sacrificing love for Christ encountered in the poor drew her more deeply into the suffering and joy of a life worth living. Thus students complete their study with a contemporary account of happiness sought and happiness found in the message and person of Christ.