The new School of Nursing's plan is in motion for fall.

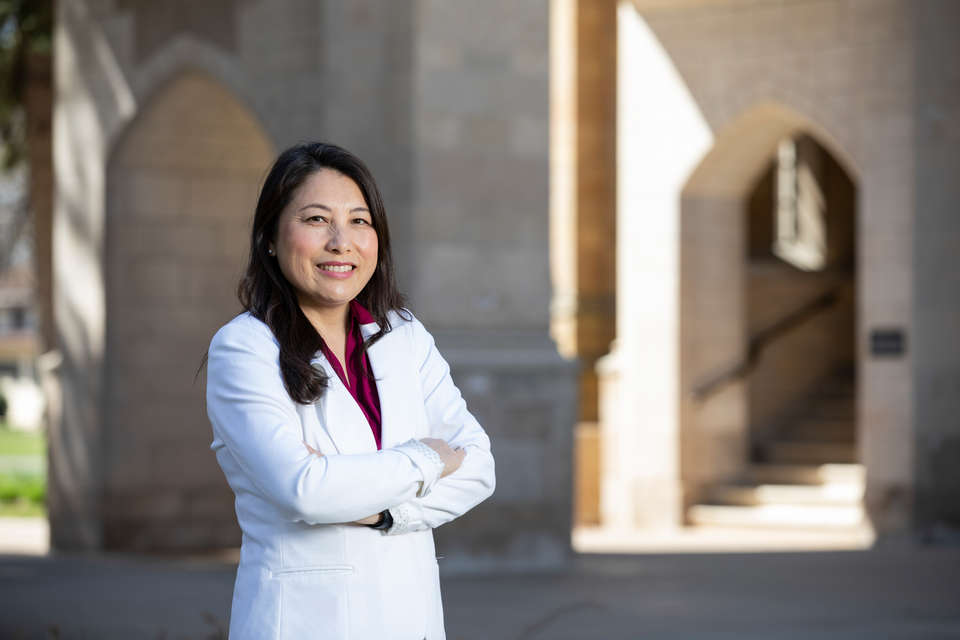

When Dr. MayKao Hang, vice president of strategic initiatives and founding dean of the Morrison Family College of Health, was charged in fall 2019 with developing a plan to launch the School of Nursing at the University of St. Thomas, she essentially had a blank slate. But there was no doubt in her mind about how to proceed.

She envisioned a culturally responsive program that would educate students who would learn to treat the whole person – their mind, body, spirit and community – and promote health and wellness in a way that would also advance health equity and social justice.

After two years of planning, approval from four governing bodies, and the co-leadership of founding director Dr. Martha Scheckel, the School of Nursing at the Morrison Family College of Health is on track to open its doors to its first cohorts in fall 2022.

The School of Nursing is launching at a befitting time, as the nation is in a health crisis. Health care disparities persist among those who are low income, those of certain racial and ethnic groups, and those in rural areas. The issues are exacerbated by both aging baby boomers with growing medical issues and exiting nurses entering retirement or other career opportunities.

The good news is the curricula and enrollment goals of the School of Nursing could help solve the growing health inequities in this country: matriculate more students who want to become nurses but give them the tools to better understand how their actions and leadership can lead to systemic change.

“When you set a goal like that, it’s to motivate us into action,” said Hang, who noted that teaching culturally responsive care isn‘t unique to St. Thomas‘ nursing school, but as a new program it‘s easier to start out the door in this direction, rather than retrofitting changes into an outdated model.

A plan to achieve health equity

“Our School of Nursing has very distinct goals around closing health equity gaps,” St. Thomas President Julie Sullivan said. “We are dedicated to increasing access to culturally responsive care, with a goal of enrolling at least 30% students of color and students from other underrepresented backgrounds.”

Men as well as African Americans and people who are Latinx are greatly underrepresented as registered nurses (RNs) when compared to the general population, according to the National Council of State Boards of Nursing. While there is less of a gap for Asian Americans locally in Minnesota, the numbers are still concerning given the growing demographic, according to Minnesota Board of Nursing data. A diverse nursing workforce is essential for progress toward achieving health equity in the U.S. Studies show that when nurses reflect the patient demographic, communication is enhanced, patient satisfaction increases, and outcomes improve.

The School of Nursing at St. Thomas defines diversity more broadly than just by race or gender. The school seeks to enroll a significant number of students from rural communities, students who are first-generation, students of color, and students who have otherwise been historically excluded from higher education. It will initially accommodate 100 students between the four-year bachelor’s degree program and the 20-month master’s program, with both programs designed to help students become RNs.

Diversity among nurses is a good start, but it is just one of the building blocks for more equitable health care, said Scheckel, a community and public health nursing expert who came onboard as the school’s founding director in fall 2020.

“The skills required to truly advance health equity include critical thinking, clinical judgment and actions from nurses to address needs of diverse patients, far beyond their own social identities,” she said. “Though you take care of the individual’s physical, emotional and spiritual needs, you also need to be very attentive to the social determinants of health, including where people live, work and play.”

Educating the ‘Tommie Nurse’

Built into the School of Nursing curricula are clinical placements to help students better understand how socioeconomic factors play into health care. In addition to practicing acute care at medical centers, placements will occur in unique community settings such as the Minneapolis Downtown Improvement District where students will engage in “boots on the ground” outreach.

“I’d love to see things like pop-up clinics, where students can provide health promotion and health education,” Scheckel said. “For example, blood pressure screening might be one of the most important prevention activities a nurse does. It’s not a high-tech intervention, but it could prevent a stroke.”

“Our School of Nursing has very distinct goals around closing health equity gaps.”

President Julie Sullivan

When Hang discusses how students will have real-life learning experiences with individuals who experience trauma, such as the unhoused population, she hears some people ask: “Won’t that be scary for students?” Hang responds: “We‘re human beings; we can‘t be scared of the people we‘re serving. We have to expose students to what they will see when they finish school as nurses. They will see homeless people, whether they’re in an emergency room trying to preserve life or caring for kids who have cancer.”

Hang knows that these issues are intersectional. “Half the people in Minnesota who are living on the streets are children under the age of 18. Our nurses have to know how to serve them.”

Because the mission of St. Thomas is focused on Catholic social teaching and serving the common good, Hang and Scheckel see such placements as transformational opportunities for students in a supportive, high-touch learning environment guided by experienced nursing faculty.

“You’ll know when a registered nurse is a Tommie nurse,” said Scheckel. “It’s a signature that shows that the student came from an outstanding program and is an excellent nurse because of it.”