Everybody grieves. It is part of the human experience. Yet, it is often misunderstood. To address this emotional process, the University of St. Thomas has launched Good Grief, St. Thomas, a new interdisciplinary initiative on grief literacy. The partnership through the Family Studies program and the School of Social Work is part of a global movement designed to increase public awareness and understanding of grief as a normal response to loss and encourage relevant support.

“A grief-informed community is one where it’s OK to not be OK, where you’ll be met with understanding, not judgment,” said Professor Audra Nuru , director of the Family Studies program in the College of Arts and Sciences, and Endowed Chair of Social Sciences.

As a co-organizer of the Good Grief, St. Thomas initiative, she pointed out that Good Grief is well suited for St. Thomas’ Catholic mission “because being grief-informed focuses on the dignity of being human.”

Grief met with compassion can fuel incredible levels of support – the flood of food, flowers, cards and compassion. It can unite a family, a school, a community. It can be a catalyst for incredible transformation in individuals, families, communities and nations. When grief isn’t supported, there are personal and societal repercussions, said co-organizer Melissa Lundquist, an associate professor in the School of Social Work at St. Thomas’ Morrison Family College of Health.

“Grief that’s not tended to can lead to people missing work, using medical care at higher levels, and not being able to hold down a job because they can’t go to work,” said Lundquist, who is also the director of the bachelor’s in social work program.

Normalizing grief

Good Grief, St. Thomas will launch with a week of grief literacy events in various locations on campus from Nov. 11-14. The events and the ongoing initiative aim to engage students, staff, faculty and the community in learning and embracing grief through artwork, discussions and community bonding. There will be a memorial tattoo project, a celebration for Dia de Los Muertos, panel discussions, and other events where people can openly discuss grief.

“Grief is not something that should just happen in a therapist’s office, but should happen in our families, neighborhoods, schools, police departments, and even in our mayor’s offices,” Lundquist said. “I believe grief needs to be seen as a normal part of being human and not something to be ‘handled’ or ‘dealt with’ quietly or in isolation.”

Creating spaces for open dialogue about grief can prevent the phenomenon of “suffocated grief,” a term coined by Dr. Tashel Bordere, a grief scholar and researcher at the University of Missouri-Columbia who will give the Good Grief, St. Thomas keynote address in James B. Woulfe Alumni Hall, in the Anderson Student Center on Nov. 14.

Suffocated grief occurs when people’s grief is dismissed or actively punished, the professors said. Such feelings can lead to shame or isolation and can discourage or stifle individual healing.

“I feel like grief gets this bad rap of ‘Oh, I don’t want to discuss this. I don’t want to feel bad,” Nuru said. But the Good Grief initiative hopes to change that. “We want to start transforming ideas about grief, and support people in understanding that grief is a central part of being human.”

Grief comes in many forms

“Grief unfolds uniquely for each person, like a fingerprint – whether it be the loss of a loved one, a cherished pet, a relationship, a dream, or even a sense of identity,” said Nuru, emphasizing that grief doesn’t follow a single, predictable path. She explains “It’s not like climbing a ladder where you step neatly from denial to anger to bargaining and so on. It’s more like a meandering path with twists and turns, unexpected detours, and moments of breathtaking beauty along the way.”

One of the most visible public expressions of grief – and one of the most misunderstood – is protesting, “Good faith protesting – not rioting,” Lundquist clarified. After the death of George Floyd, protests erupted across the world, expressing collective grief over his loss and calling for justice. “When we respond with compassion, then they feel their grief has a place that starts to feel right, but when we shut it down, then it actually explodes in ways that aren’t helpful,” she added.

“When we allow public expressions of grief to be seen and supported, it helps people feel that their grief has a place to heal,” Lundquist said. Too often, however, these expressions are met with resistance. Lundquist explained that this reaction can intensify feelings of isolation and alienation for those already grappling with their grief.

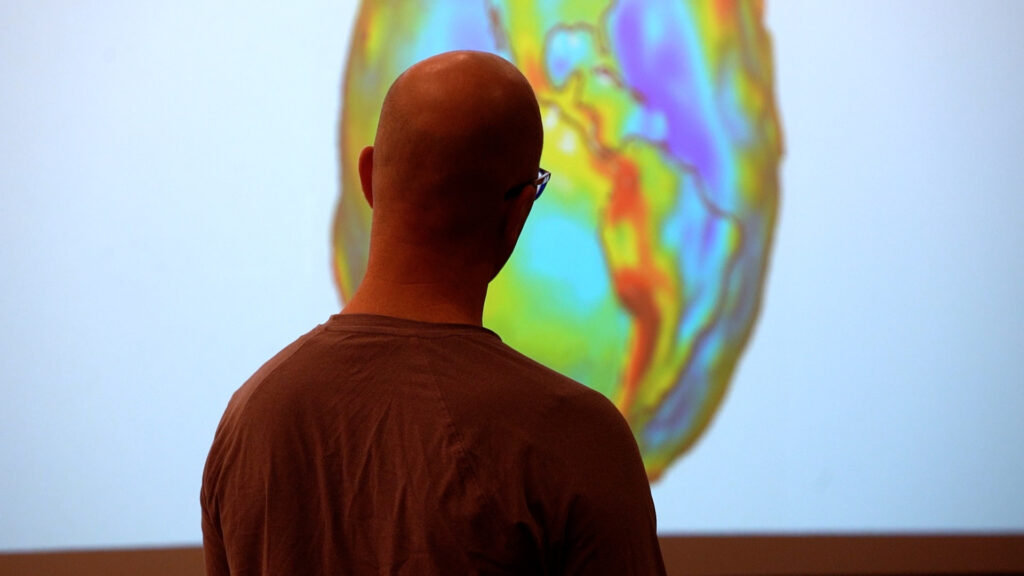

For Lundquist, the importance of grief literacy became clear through her experience as a social worker helping families living with cancer. She explained that grief is a “fully embodied response to loss – it impacts the way we think, the way we feel, the way we behave, and what we believe. It affects every part of who we are.”

Grief, Lundquist added, “isn’t something you just ‘get over’ or ‘move on’ from. It’s something we learn to carry, and that’s OK.”

Nuru shared, "everyone grieves in their own way, and your experience is valid, no matter what it looks like."