It’s easy to imagine that such a moment deserves a big, red lever between the words ON and OFF and the tension before the switch gets flipped.

Instead, Xcel Energy CEO Ben Fowke reached out his hand on Nov. 1 last year, standing in the basement of the St. Thomas Facilities and Design Center (FDC) on the St. Paul campus. Reaching down, his hand hovered over a computer mouse, his right index finger swung down, and just like that he officially turned on the brand-new Center for Microgrid Research. The system’s response kicked off a chorus of applause from everyone gathered, as the moment represented the culmination of a $2.1 million grant from the Xcel Energy Renewable Development Account, years of faculty and student efforts and construction going back to the summer of 2016.

Xcel Energy CEO Ben Fowke and President Julie Sullivan listen as Engineering Professor Mahmoud Kabalan gives a tour of the Microgrid control center. Mark Brown/University of St. Thomas

Now officially operational, the St. Thomas Center for Microgrid Research is one of just a handful of premier research and educational facilities of its kind in North America. It will be available for research and partnership with companies and schools across the country. The facility’s value in helping develop technology – and training innovative St. Thomas engineers and technology leaders to shape the evolution of energy in the face of climate change – is seemingly limitless.

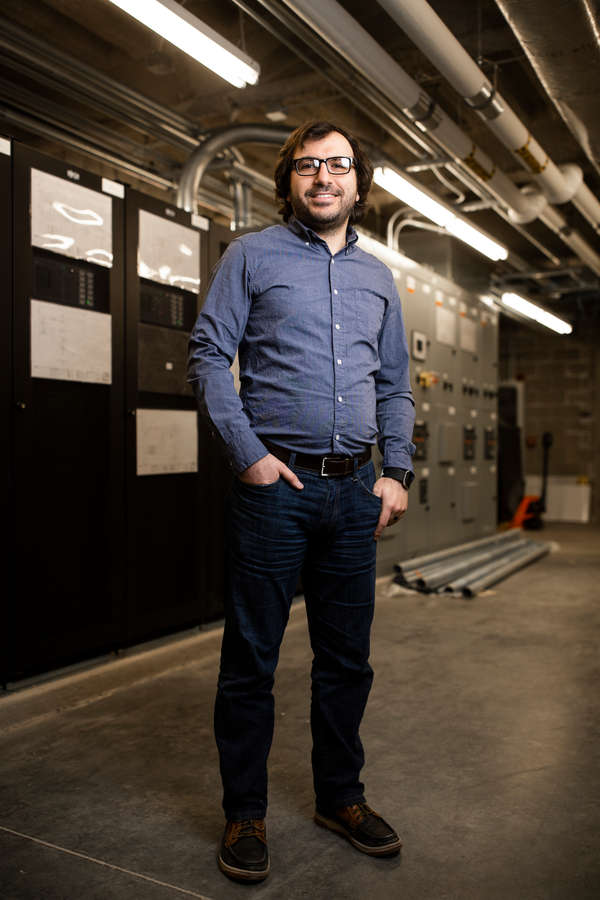

“This facility is nearly unique in the U.S. It will help us attract students, research, industry partners. It’s wonderful to be at this stage,” said Dr. Mahmoud Kabalan, director of the Center for Microgrid Research. “We’re setting people and our society up for the future through our students. We’re producing people who will go out and be leaders in the field with very strong technical backgrounds. We’re producing the engineers of the 21st century."

“There are only a handful of facilities like this in the country,” said Dr. Greg Mowry, who leaned on decades of experience in the power sector and with microgrids to custom design the St. Thomas facility. “On the playing field of advanced research in the power sector, that puts us not equivalent, but ahead of nearly everybody.”

An island of power

The term “microgrid” has moved onto more people’s radars in recent years as renewable sources of energy continue to be explored and implemented throughout the United States and the world. As with any electrical system, it contains a certain number of sources (things that generate power) and loads (things that receive power). A microgrid acts as a single, controllable electrical system that allows smooth renewable energy integration, and can operate either connected to the wider power grid or as an independent “island” of power.

The St. Thomas microgrid consists of:

- A 48 kilowatt (48,000 watt) solar PV array, located on the roof of McCarthy Gymnasium and the FDC

- One 50-kilowatt biofuel Genset generator

- A connection to the grid through Xcel Energy

- A 125-kilowatt/396 kilowatt hours lead acid battery storage

- The capability to emulate different electrical sources or loads using state-of-the-art electrical power research equipment

- The capability to test third-party equipment up to 125 kilowatt

- Controllable load devices up to 250 kilowatt

Mowry designed the energy sources to be of similar capacity; there isn’t a single, dominant energy source, unlike most microgrids, which allows for incredible flexibility with research and experimentation for what elements can be introduced and studied. Combine that fact with the scale and capabilities of the St. Thomas microgrid, and you have a rare gem of a facility for external partners to collaborate with St. Thomas.

Engineering professor Mahmoud Kabalan. Liam James Doyle/University of St. Thomas

“A lot of the technology that went into it is usually reserved for high-end research universities and private labs that put in millions in investments … and cost hundreds of thousands of dollars to access,” said Kabalan, who joined St. Thomas in 2017 and brings a wealth of research experience on microgrids. “What we have here is geared toward undergraduate and master’s level students, on top of the fact the technology and hardware that went into it are state of the art. There are few facilities that can do what this one can, and the fact it’s not behind a secretive, sign a nondisclosure agreement process to see what you’re doing, is amazing.”

The facility’s openness is a fitting extension of St. Thomas’ already superb foundation of industry collaboration, which the School of Engineering has cultivated for years.

“With our focus on working directly with industry partners, there are some unique attributes with what we’ve put together,” Dean Don Weinkauf said. “The dream has been for companies to be able to come in, plug in their components and see how they interface in a microgrid environment. We can now do that.”

For the key partner to this point, Xcel Energy, the results already speak for themselves.

“The St. Thomas Center for Microgrid Research is a great example of two partners with a shared vision to reduce carbon emissions working together to benefit students, the university and the environment,” said Chris Clark, president of Xcel Energy-Minnesota. “The technologies that students and companies are testing at this facility could someday play an important role in our clean energy future. We’re proud of the partnership we have with St. Thomas and the School of Engineering and look forward to a bright future of working together.”

A powerful road

What flows through the microgrid is remarkable on two levels.

On the one hand is power, the all-important energy on which our society depends – and desperately needs to improve its relationship with in relation to climate change.

On the other hand, is empower: From day one, St. Thomas students have been trusted and empowered to contribute to the microgrid throughout its entire construction, imbuing the facility itself with a spirit of learning and potential just waiting to be realized.

Solar panels for the Center for Microgrid Research stand atop McCarthy Gym. Mark Brown/University of St. Thomas

“When you figure new stuff out, it’s not always going to work. Keep going. Don’t be afraid of it,” Mowry said of the attitude he passes on to his students, dozens of whom have contributed to the microgrid. “The moment they crack open a door and see that glimmer of light, they see they’re capable. That’s the greatest thing any teacher can do for a student. … That self-awareness and potential is a major change in the way a person views themselves in life. That’s what these kinds of projects unleash.”

Students who have been part of the microgrid over the past three and a half years are the living testaments to that: The benefits are incredible for both undergraduates and graduate students, particularly those of the burgeoning Master of Science in Electrical Engineering, the growth of which has coincided with the microgrid’s development since it was first submitted as a grant in 2011.

“The microgrid and the master’s program were premeditated to increase the reach, provide a venue of [research and experimentation], that has been realized today,” Mowry said. “All the electrical engineering faculty are involved with the grad program and have students doing research. … We’re providing the mechanisms and paths where students can excel rather easily up to the master’s level, which buys a big bang for students moving up and into the workforce. It’s such an enabler on so many fronts.”

It hasn’t taken long for students to recognize the value the microgrid offers to their education: MSEE first-year Shaun Ly described submitting his resume “the minute I found out about it” and said the experience has been “amazing.”

“Being able to work with equipment that’s used in industry is really helpful; there’s so much you can do with this,” said Ly, who’s one of nine students currently working with the microgrid. “Dr. Kabalan has a lot of experience, so much knowledge we can soak up as we go and work together.”

“Being able to work with equipment that’s used in industry is really helpful; there’s so much you can do with this,” said Ly, who’s one of nine students currently working with the microgrid. “Dr. Kabalan has a lot of experience, so much knowledge we can soak up as we go and work together.”

Kabalan said it’s easy to envision the capacity for 30 to 40 students working on the microgrid in the near future as partnerships grow and research opportunities arise. Weinkauf said he heard a straightforward assessment of this kind of experience for students from Fowke as they left the FDC following the flip switch ceremony: “Ben said to [President] Julie [Sullivan], ‘Xcel would hire every single one of those students in a heartbeat. No one else is getting this kind of experience,’” Weinkauf recalled.

Sophomore Rachel Pietsch joined the team as a first-year and has felt that value as well, including when her father, an electrical engineer, noted how many of the components and systems are the same at his company.

“It has been really exciting. This opportunity has opened so many doors for me,” she said. “I’ve been in interviews with companies working with microgrids, and they’re so excited undergrads are getting the chance to work on them. Seeing how learning these skills can help me in industry is huge, especially when microgrids are becoming a pretty big part of combatting climate change .”

Solving the big problem

The microgrid represents a significant step forward in St. Thomas’ ability to contribute to the ongoing effort to combat climate change. In aiding the development of renewable energy technology, St. Thomas has an even more active part in the future. “We are building what hopefully you will see in your home in five to 10 years,” Kabalan said. “We’re building technology that, just like a cell phone, will be very normal. … Energy production will either be 50% of the problem or 50% of the solution. We’re part of the solution.”

The microgrid also represents a continuation of the school’s desire to educate “a different kind of engineer,” producing students with an understanding of their place in the world and a desire to use their skills to make positive impacts.

The microgrid also represents a continuation of the school’s desire to educate “a different kind of engineer,” producing students with an understanding of their place in the world and a desire to use their skills to make positive impacts.

“The kind of education here at St. Thomas, it’s real stuff,” Weinkauf said. “The more you’re out of the textbook and in the real space, the better of a problem-solver you’re going to be. That is part of the philosophy that’s captured in the [microgrid] system we’ve built. What’s important for students to understand is that there are no silver bullets to these big problems. It’s the synthesis of a lot of ideas, a lot of technology, a lot of work, which is all carved away with small steps. … It’s going to be an aggregate of a lot of types of solutions in that space of energy independence and security. All of those things are not just going to happen; there’s a lot of work to be done.”

More than ever before, St. Thomas is poised to – as Mowry described it – “roll up our sleeves and get to that work,” emerging as a national leader going forward, where the possibilities remain endless. Pietsch gave voice to the personal vision she is moving toward, which is to secure her master’s degree in business administration after her electrical engineering degree.

“The end goal is to help lead in making microgrids more affordable to the average consumer and spreading this technology,” she said. “Being able to take the experience of engineering and applying it to a business degree, then combining those to help save the planet? I can do that here.”