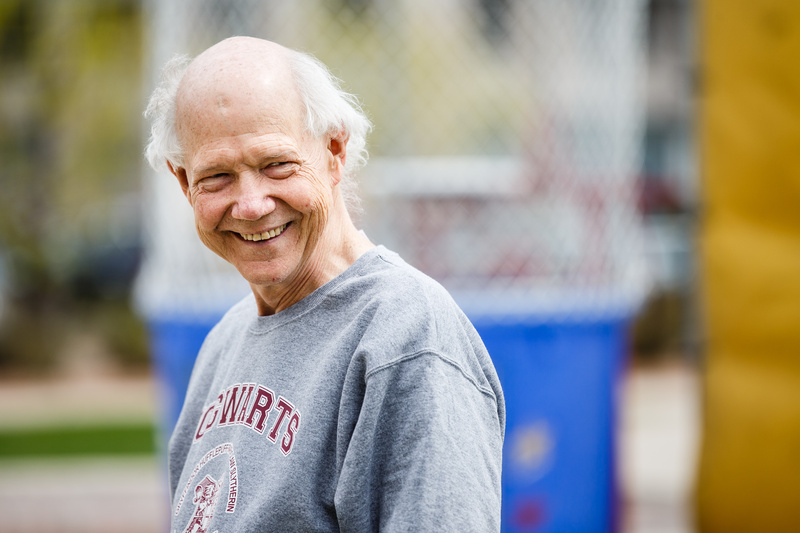

At the heart of every court case is a real person. Law Professor Greg Sisk motivates his students with this sentiment as they work in the Federal Appellate Clinic he founded at the St. Thomas School of Law.

He said he created the clinic “to provide service to the profession … and to the disadvantaged in a place where my talents are particularly strong.”

The Appellate Clinic specializes in prisoner civil rights cases, in which prisoners have been mistreated by prison officials. “These are individuals who are treated by society as the least deserving,” said Sisk, Pio Cardinal Laghi Distinguished Chair in Law, which is endowed by John and Susan Morrison. “They’ve been thrown away in a prison somewhere. They’ve been subjected to indignities most of us can’t imagine. People don’t take them seriously and regard everything they do or say with cynicism.”

One of his goals is to make sure clients feel heard. Sisk wants them to come out feeling like they had someone on their side who worked to the best of their ability.

The clinic students’ hard work has paid off; they have won an appeal each of the past five years.

The 9th Circuit

Although attending classes in Minneapolis, the School of Law’s Appellate Clinic students work on cases in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit, which covers nine Western states. Sisk clerked within that circuit and said it is set up well for law school clinics.

Because the U.S. Supreme Court reviews fewer than 2 percent of the more than 7,000 cases filed annually, the U.S. Courts of Appeals serve as the final arbiter on most federal cases.

As a court that deals with appeals, a panel of judges determines whether the law was applied correctly by a trial court judge. In many of these cases, appellants are handling their own cases without the aid of an attorney.

In the 9th Circuit, judges may review a brief filed by a “pro se” party (that is, someone without a lawyer), and, if they believe there is something within the brief that would merit an attorney reviewing it, they make it available to them. Attorneys then have the option of taking on the case and providing their services pro bono.

“It makes it a lot easier for [judges] to understand the legal arguments because they don’t have to sift through a brief that may have a lot of legal errors and see if there’s something among the weeds,” Sisk said. “We do the pruning process for them and provide a stronger legal argument.”

St. Thomas’ Appellate Clinic is among those invited to review the court’s list of possible pro bono cases. Sisk, along with the help of two students per year, takes on a case. Over the course of an academic year, they review all documents associated with the case, draft two new briefs (an opening and a reply) and then argue the case. Some cases have continued for more than a year and involved different students.

Honoring the dignity of the human person

Prisoners, even those who have suffered mistreatment by prison officials, are wary of working with attorneys.

“They haven’t been well-treated by lawyers and the judicial system in the past,” Sisk said. “They’ve been convicted of a crime, often with an attorney who … was not fully responsive to their concerns.

“They typically are cynical and untrusting of lawyers,” Sisk said. “We know we need to give them the confidence so they come to trust us and know we are a part of their team and are really looking out for their interest. We are concerned about them not just as a project, but as a person of dignity.”

When they work through a draft of a brief, Sisk ensures that he and his students maintain the heart of the argument that the client originally laid out.

Unsurprisingly, for many clinical students creating lasting relationships and making a difference in the judicial system are hallmarks of their law school experience.

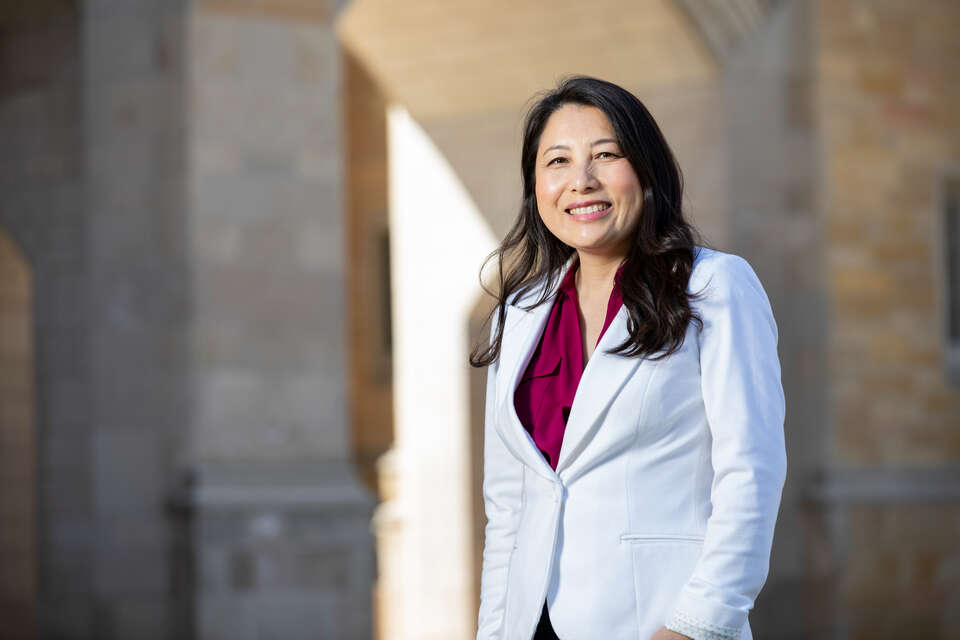

“It doesn’t compare to anything else you can do in law school,” said Katie Koehler ’17 J.D. “It was so cool to know that I helped work on a case that had a significant impact on someone’s life and hopefully will prevent this issue from happening again. It’s still and probably always will be one of my biggest professional accomplishments.”

The Appellate Clinic is of interest to many law students who pursue a position with one of the School of Law’s 12 clinics. Because Sisk only takes on two students a year, the process is highly selective.

“The Appellate Clinic is one of those clinics that every law student wants to do,” said Caitlin Hull ’16 J.D.

The clinics, in general, are in line with the hands-on experience that many graduates say they appreciate about their St. Thomas experience.

“I liked the idea of going somewhere you get a practical education,” Hull said, “not solely academic, but learn how to actually practice law.”

For many in the Appellate Clinic, that practical education was supported by their close interactions with faculty, including Sisk. Several who participated in the Appellate Clinic had learned about it while in Sisk’s classes.

Once in the clinic, Sisk puts the students through their paces, finessing their research, written and oral argument skills to near perfection.

“Professor Sisk has really high expectations – it’s a challenge, but it’s a blessing,” said Bridget Duffus ’14, ’17 J.D. “If you do something, you might as well do something exceptionally well. I was constantly challenged in everything I was doing, but I’m really grateful for that.”

Practicing to perfection

Sisk walks the students through at least a dozen drafts of a brief, and when they turn their attention to the oral argument, he expects both students to know all parts of the brief. He helps them practice by asking questions that might arise and bringing past clinic students in to grill them as well.

“Professor Sisk takes you through a significant and stressful moot practice,” Hull said. “You’re getting all of these questions – so you’re forced to look at the case in a new way. It challenges what your strongest parts are or what you thought they were.”

While the participants expressed gratitude for the rigorous approach Sisk employs, Sisk added that he learns from his students as well.

“This is what it’s like to be a senior partner at a major law firm with two really bright associates,” Sisk said. “I think all of my clinic students would say that there are times they’ve convinced me that my initial approach was mistaken or that they had a better approach.”

The ability to work with clients while still in law school attracts students to the Appellate Clinic.

“I wanted an opportunity for something that mattered,” said Lindsay Lien Rinholen ’15 J.D. Her experience reaffirmed her belief that she could make a difference through a profession in law.

“We were three people, and we made a difference,” she said. “You don’t see that as often as you should. We like to think that it’s easy to believe that one person can’t make a difference. … Never forget that you can change the world, at least for one person.”

Appellate Clinic victories

Scott Nordstrom v. Charles Ryan, et al.

Arizona death row inmate Scott Nordstrom appealed that prison guards should not be able to review legal mail between inmates and their counsel. Joy Nissen Beitzel ’14 J.D. and Michelle King ’14 J.D. argued that this interferes with the confidential attorney-client relationship.

The case returned to court a second time, where it was handled by Katie Koehler ’17 J.D. and Bridget Duffus ’14, ’17 J.D.

After winning the appeals, Sisk convinced the lower court to permanently enjoin the Arizona Department of Corrections from reading or skimming prisoner letters to attorneys.

Chet Wilson v. Joan Copperwheat

Chet Wilson brought a civil rights suit against Oregon correctional officials for wrongfully returning him to prison for seven months based on false charges that he had violated disciplinary rules for transitional release. The District Court dismissed Wilson’s lawsuit as having been filed too late under the statute of limitations.

Lindsay Lien Rinholen ’15 J.D. and Colin Seaborg ’15 J.D. explained that a civil rights action for wrongful confinement cannot be filed until after a prisoner has successfully sought other remedies, including use of prison administrative procedures, to obtain release, and Wilson’s lawsuit was within the statue of limitations.

After the Appellate Clinic won the appeal, the state agreed to a substantial settlement.

Oray P. Fifer v. United States

Oray Fifer, a federal prisoner, was in the Federal Correctional Institution in Phoenix when a race riot broke out. Although Fifer did not participate in the riot and was running to return to his cell as ordered by correctional officers, he was shot in the head six times by dangerous, less-lethal rubber munitions. The final shot to the face – which permanently damaged his left eye – was fired when Fifer was down on all fours.

Caitlin Drogemuller ’16 J.D. and Catherine Floeder (nee Underwood) ’16 J.D. contended that the United States has the burden of proof because justification is an affirmative defense, and that the government cannot establish that shooting Fifer in the face while he was down on the ground was so clearly justified as to permit rejection of his claim before trial.

After the Appellate Clinic won the appeal, the case went to trial and the prisoner won damages.

Darrell Harris v. S. Escamilla

The case was brought by Darrell Harris, a California state prisoner and leader of Muslim prisoners, whose Quran was desecrated by a correctional officer while Harris was away at vocational training. Four prisoner eyewitnesses report they saw the officer search Harris’s cell, seize his Quran, angrily throw it to the floor, stomp on it for the prisoners to see and kick it under the bed. Finding his most sacred possession on the floor when he returned, Harris was heartbroken and unable to continue his daily duty to read from the Quran because it had been desecrated.