Souleymane Kone is the kind of student who keeps a professor on his toes.

That’s how School of Engineering Professor Manjeet Rege described him, and Rege should know: At the end of the 2017 fall semester, Rege was waiting in line for coffee in Owens Science Hall on a 15-minute break during the daylong graduate Data Analytics and Visualizations class in the graduate data science program. Kone – one of the most engaged students in the course – wanted to talk to Rege about a grant he was trying to secure to support building data analytics capabilities in Ivory Coast. It seemed like a long shot.

“He approached me in such a casual manner, like this was no big deal. He was such an engaged student, I couldn’t really say no,” Rege said. “He kept me updated about the process and challenges of the proposal, which was against a lot of others. OK, fine, I kind of kept on nodding. This went through spring class, which was also with me [after Kone decided to pursue big data management and continue working toward an MS in data science.]”

Then, that long shot hit.

“At the end of April or early May he said to me, ‘I’ve got it,’” Rege said. “This is when it hit me: ‘Souleymane has struck gold.’”The two-year, $2 million grant from the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) – a U.S. foreign aid agency that forms partnerships with developing countries committed to good governance, economic freedom and investing in their citizens – and the President's Emergency Fund for AIDS Relief, supports the growth of data capacity in Ivory Coast. Since securing the grant, Kone, Rege and St. Thomas have already had massive impact toward Kone’s decades-long goal of bringing technological knowledge and application to Ivory Coast. A prime example was in applying data to ministry decision-making of where to build new middle schools.

“This has always been the motivation for me, to come and learn, and transfer some of that knowledge back home,” said Kone, who first came to the United States in the late 1990s and has worked in corporations in the U.S. and France since. “When I go all over, people say, ‘We understand your [connections with] St. Thomas, but that’s not the only university.’ I know where I feel at home and cared about. … I’m not going anywhere. I found the energy I’m looking for [at St. Thomas], the right mix of entrepreneurship and savviness, technology and statistics.”

As the partnership continued, more and more opportunities unfolded.

“This,” Rege said. “Is really just the beginning.”

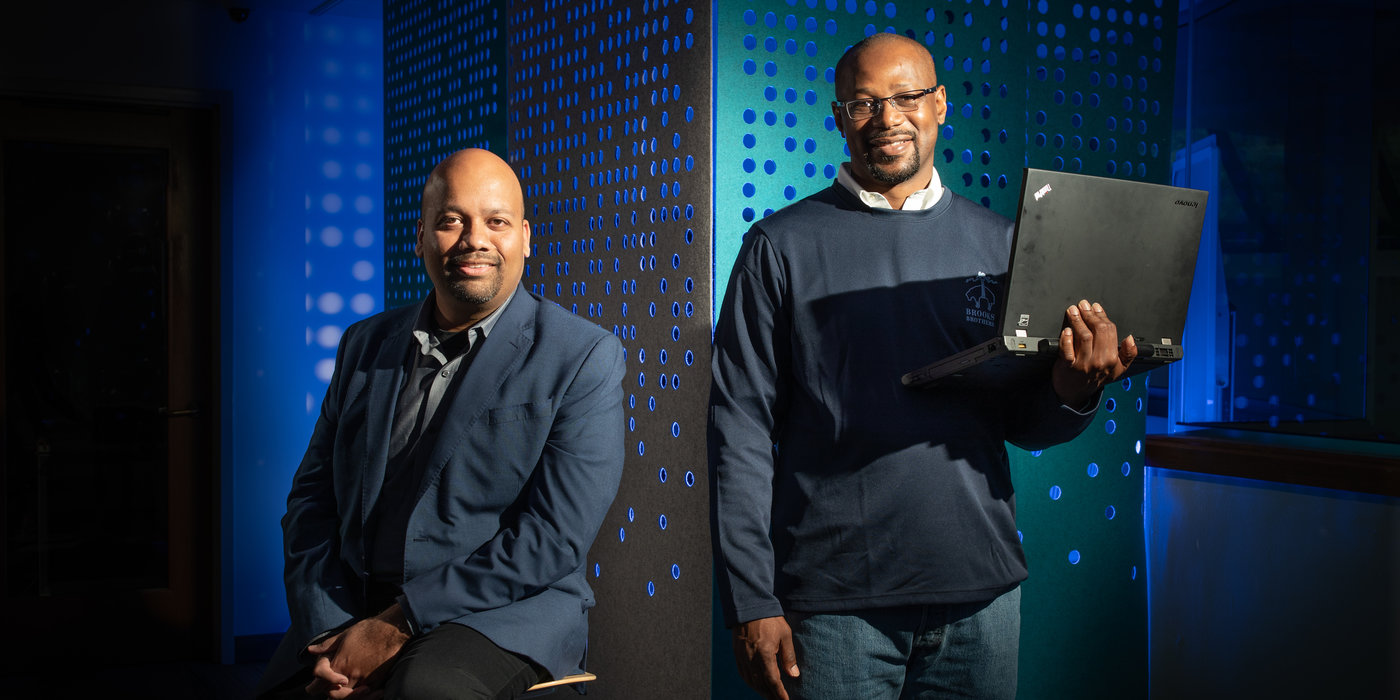

Data Science master’s student Souleymane Kone works on a data analytics project in the STELAR lab in O’Shaughnessy-Frey Library in St. Paul. Mark Brown/University of St. Thomas

Growing fast

Over three trips in summer 2018 and winter 2019, Rege flew to Ivory Coast and taught a core team – about a dozen people – how to teach a two-month data science crash course. Since then, that team has trained more than 120 “data fellows,” who get the necessary education in machine learning, big data, statistics “to create a foundation,” Kone said.

“They learn enough to be employable in the data field, or it can ignite a spark for them to get more education down that path,” Rege said. “Going through this can give someone enough footing to take the next step.”

Recruiting Rege to train his core team, Kone said, was “a no-brainer.”

“I have the passion to do things right. Being a good data scientist, analyst, entrepreneur, for that matter, is recognizing when you don’t have the skills to deliver the type of quality you have to,” Kone said. “So it was natural for me to approach the teacher who unlocked that passion of data science in me. He took this team and the module he teaches in a semester, and had to teach it in basically a week. So, seeing how people responded to that, the enthusiasm and engagement, for me was a ‘wow.’”

According to Kone, a major reason he sees so much potential for data to expand in Ivory Coast is the strong foundation of statistics, which is a common field of collegiate study and strength of ENSEA, which produces the majority of statisticians in Ivory Coast and throughout western Africa, Kone said. That background is a fantastic primer for data science, so the fellows entering Kone’s program are not starting from scratch.

“There’s big potential here,” Rege said. “In graduate programs in software at St. Thomas, we take pride in helping career changers. … This is a huge example, as here are people with degrees in statistics; it’s a huge potential to be tapped as they move into data science.”

As data fellows have moved through the certification process, the next step Kone’s project took was to infuse their newly-developed talents into the health and education sectors: For nine months they are placed – at full pay – into organizations to deploy data solutions.

“In April 2020, when all the fellows are done, we will have a career fair with the private sector to demonstrate what they did, showcase the results and value, and get them placed in the private sector,” Kone said.

The value of the project proved itself throughout MCC’s evaluation process, which Kone said happens every six months and involves a weeklong site visit.

“When we did our presentation on day two, [the inspector] told her colleague, ‘I think we can go,’” Kone said. “That felt good. It shows that we know what we’re doing.”

As Rege’s work with ENSEA and its School of Statistics continued, the connections with faculty led to a desire for even more opportunities: In August, the St. Thomas School of Engineering and ENSEA signed a formal Memorandum of Understanding.

“This can lead to all kinds of academic cooperation, faculty exchange, St. Thomas helping give input about data science to ENSEA so they can continue developing academics around it,” Rege said.

Data Science master’s student Souleymane Kone works on a data analytics project in the STELAR lab in O’Shaughnessy-Frey Library in St. Paul. Mark Brown/University of St. Thomas

New opportunities

Part of the project’s proof of value has been in the way Kone and his colleagues have applied data insights for the Ivory Coast government. A ministry there was tasked last year with determining the best locations for new middle schools to be built; without data insights to inform that decision, Kone said, such decisions in the past were seemingly arbitrary or based purely on political capital.

Kone’s team overlaid information the ministry gathered – geographic and infrastructure (electricity, roads, etc.) data – and helped established parameters: If you want 90-120 middle school-aged children to be within walking distance (five kilometers, including around physical barriers like water, which GIS technology allows Kone’s team to account for) of a school, where should they be built? Armed with data from Kone and his team, the ministry had their answers.

“It was great to be able to [help with that project],” Kone said. “And it’s reusable. Now if they have another buyer or funding to build schools, they can run the model again. … Now they have a tool they can use with the push of a button.”

The Ivory Coast’s recognition of Kone’s value extended recently back to American soil, where the country’s embassy in Washington, D.C., offered to support his work further. The embassy offered a two-story building it owns with 12 office spaces to Kone and his team at a subsidized rate. Kone plans for it to house an incubator for students and businesses to develop ideas and projects to positively impact western African countries.

“We will host them, free of charge, for six to 12 months, and give them all the tools they need to be successful, and then deploy and support them,” Kone said. “It will be like an accelerator so they can have an impact right away.”

Kone’s team is currently accepting applications for four students or businesses to begin in January, with “some preference for technology, AI, smart agriculture projects or ideas. But we’re not going to disqualify someone because they have a great idea [that] doesn’t fit in those boxes,” Kone said.

The School of Engineering will also support the incubator, providing participants access to faculty expertise and, potentially, student internships or research support, which could stem naturally from the required capstone experience of the data science program.

“We are very well positioned to be a strategic partner on this,” Rege said.

Kone and his team’s expertise and extensive relationships in western Africa promises to be a huge benefit to development in the incubator, in large part because their knowledge of the context where those ideas and projects could be deployed is invaluable.

“You can have the best solutions, but if you don’t understand the context of where you’re going it can fail,” Kone said. “This incubator will hopefully help them have that view [of where this will be applied], including all those legal and compliance aspects [that may be different from the U.S.].”

Data Science master’s student Souleymane Kone poses for a portrait in the STELAR lab in O’Shaughnessy-Frey Library in St. Paul. Mark Brown/University of St. Thomas

A dynamic leader

As these efforts have unfolded over the past two years and continue today, it is impossible to overlook Kone’s passion as the driving force behind everything. The demands have been high: Kone’s wife and two children live in Minnesota, and this year he has maintained a repetitive schedule of 45 days in Ivory Coast and two to three weeks back home.

“The life of an entrepreneur in this way can be very challenging,” Kone said. “My family is very supportive, which helps.”

Kone’s passion has been decades in the making as he built a career following an electrical engineering undergraduate degree in Ivory Coast. He came to the U.S. in the late 1990s to study statistics and worked for a variety of companies in the subsequent years, which prompted his first interaction with St. Thomas in 2007 through courses in the Continuing Education program.

Throughout all that time he continued to develop an interest in the power of data with effective visualization and storytelling. That desire drew him back to St. Thomas in 2017 and started the process for his growing relationship with Rege and the School of Engineering. Now, together, they are bringing a deeper level of intelligence to Ivory Coast and beyond.

“That is really what drives me,” Kone said. “We’re on a mission to change the culture around data.”

“This passion really has a deep root to it for him,” Rege said. “The emphasis for him and all of this is the positive impact it’s having in Africa. That really connects with our mission here of advancing the common good. It’s wonderful.”