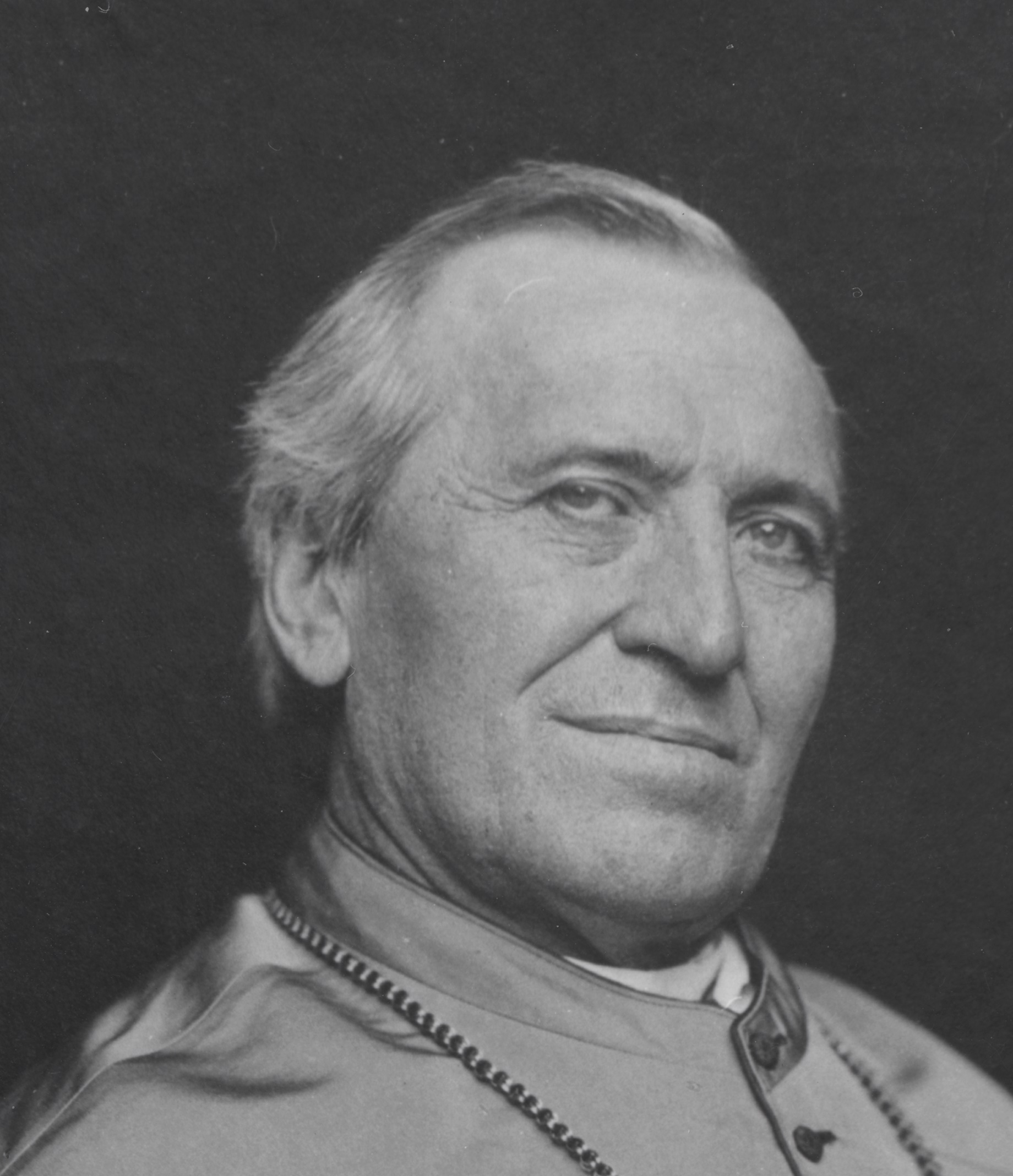

Celebrating Founder's Day 100 years after the death of Archbishop John Ireland, the founding leader of St. Thomas, the community gathered on the St. Paul campus Sept. 25. Professor of Theology Bernard Brady spoke to those gathered about Ireland's vision as a changemaker.

We stand on the shoulders of giants.

You and I are here because of the love and support of many people – the same can be said about our university. It is beautiful and strong today because of countless dedicated and generous supporters, none more important than our founder, John Ireland, whose life we celebrate today and in whose shadow we stand.

Archbishop Ireland was, in contemporary terms, a changemaker –he was a thinker, an intellectual, who was also an activist. He was inspired to envision a better society, a better America, and a more responsive church. He was also a person with the practical ability and will power to bring these changes about.

Archbishop Ireland influenced the physical, religious, social and moral landscapes of the Twin Cities in ways that rebounded through our nation and, indeed, the world.

In a time when the Catholic Church in the area was in its early stages, he commissioned two great churches – The Cathedral of St. Paul – the site of our annual Graduation Mass at the other end of Summit Avenue, and the what we now call the Basilica of St. Mary in Minneapolis. Their stunning presence continues to remind all of beauty and the transcendent.

More importantly for us, he opened St Thomas. I note here that the Catholic Church did not build St. Thomas. John Ireland built St. Thomas – with his own money and from land given to him by William Finn. In the beginning, this place was, literally, John Ireland’s college.

In a time when anti-immigrant fever was stirring, particularly anti-Catholic feelings in this county, Ireland, an immigrant himself, educated immigrants and children of immigrants to take their places of leadership in the community. As stated in St. Thomas’s original papers, “The education is comprehensive in its scope, and practical in its aims, to fit the graduates of St. Thomas for whatever walk in life their bent of mind may afterward lead them.” Ireland challenged students to “seek out social evils and lead in movements that tend to rectify them.”

In a time when Catholics and Protestants were separated by suspicion and religious divide, Ireland struck up a deep partnership and friendship with the Methodist railroad baron, James J. Hill, whose generosity founded the St. Paul Seminary. You may have noticed Hill’s house – his mansion, now a museum, across from the Cathedral. This relationship between these two of the giants in the community, this Catholic-Protestant relationship, which exited long before either church officially entered into dialogue, changed the relationship between Catholics and Protestants in the Twin Cities and modeled a culture of tolerance and respect. Indeed, Ireland went on to work with non-Catholics in towns outside of St. Paul. True leaders can hold tightly to their beliefs while working with people of differing beliefs for social good.

In a time of deep racial divide – he, a person who grew up in an integrated neighborhood, chastised racist beliefs in the Church and the country. Because of his intervention, the first two African-American priests in the U.S. received an education at St. Thomas. In 1890, he said (using 19th Century language): “There is but one solution of the problem, and it is to obliterate absolutely all color lines. Open up to the Negro as to the white man, the political offices of the country, making but one test, that of mental and moral fitness. Throw down at once the barriers which close out the Negro merely on account of his color from hotel, theater, and railway carriage. Meet your Negro brother as your equal at banquets and in social gatherings. Give him, in one word, and in full meaning of the terms, equal rights and equal privileges, political, civil, and social. I know no color line; I will acknowledge none. The time is not distant when Americans and Christians will wonder that there ever was a race prejudice.”

His vision for St. Thomas was to educate persons to be, one, fully competent in their professions and able to move within spheres of public life, and, two, be something more – be changemakers in their places of work, their communities, their nation, and indeed the world.

He has given us the great burden to continue his work, a burden that we thoroughly and happily embrace.