Ah, lists, how we love you.

You are our boundless fascination, our great collectors and organizers of data. You are our welcome respite from the seemingly endless flow of paragraphs rolling one into another. You are the delicious, bite-sized candy bars in our daily diet of information intake.

You are, simply put, beautiful.

But why? Why does this love affair burn so brightly? What is it about you that makes our connection so inherently strong?

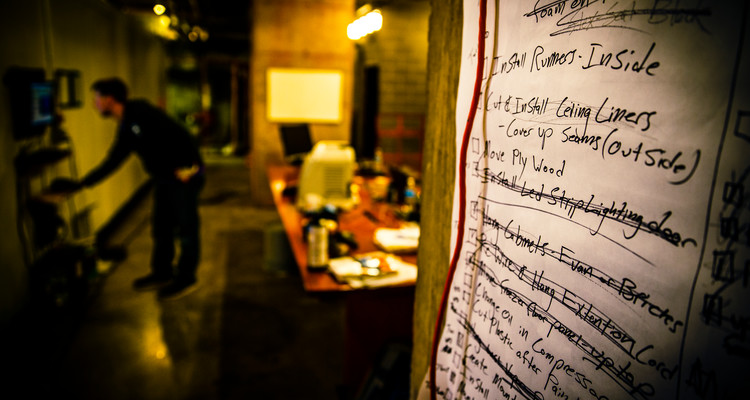

The form you take doesn’t seem to matter much; lists are all satisfying in their own way: A to-do list is unsatisfying in its representation of the work that remains, yes, but is there anything better than crossing off completed tasks and knowing what smaller bit remains? (If you’re anything like me you stack the deck of a day’s to-do list with things you’ve already done, kicking things off with the glorious sensation of visible accomplishment.) A grocery list is our life raft in a sea of aisles and tasty distractions, tethering our bank account and calorie count to the safety of a predetermined plan. A click through a Facebook link to a list of the “Top 10 songs of the 2000s” is a guilty pleasure, sure, but it is undoubtedly a pleasure.

It turns out there are plenty of reasons we dig lists so much, and – if you’re as big a fan of them as author Umberto Eco is – some of those reasons are pretty profound: “The list is the origin of culture. It's part of the history of art and literature. What does culture want? To make infinity comprehensible. It also wants to create order – not always, but often. And how, as a human being, does one face infinity? How does one attempt to grasp the incomprehensible? Through lists.”

Or, as The Book of Lists author David Wallechinsky puts it: “Lists help us in organizing what is otherwise overwhelming."

In this regard, the appeal of lists is pretty well built into our human nature. Psychologically speaking, lists hit on our desire to process information spatially; the physical layout of a list is familiar and friendly, and compared with the undifferentiated information of paragraphs “lists simply feel better,” wrote Maria Konnikova in The New Yorker.

Konnikova didn’t stop there in supporting the appeal of lists, especially online ones: “In 2011, the psychologists Claude Messner and Michaela Wänke investigated what, if anything, could alleviate the so-called ‘paradox of choice’ – the phenomenon that the more information and options we have, the worse we feel. They concluded that we feel better when the amount of conscious work we have to do in order to process something is reduced; the faster we decide on something, whether it’s what we’re going to eat or what we’re going to read, the happier we become.

“Within the context of a webpage or Facebook stream, with their many choices, a list is the easy pick, in part because it promises a definite ending: We think we know what we’re in for, and the certainty is both alluring and reassuring. The more we know about something – including precisely how much time it will consume – the greater the chance we will commit to it. The process is self-reinforcing: We recall with pleasure that we were able to complete the task [of reading the article] instead of leaving it undone and that satisfaction, in turn, makes us more likely to click on lists again.”

With a deeper understanding of their appeal in mind, the Newsroom will feature its “List of Lists,” a reoccurring series featuring topics about the St. Thomas community (Top 10 Foods on Campus; Top 10 Athletes in St. Thomas History; etc.), as well as broader cultural topics put together by experts in that given field (Top 10 Most Important American Novels; Top 10 Advertising Campaigns; etc.). We hope you’ll join us in reading what people think makes up each top 10 and, of course, arguing (OK, respectfully discussing) what should have made the list instead.