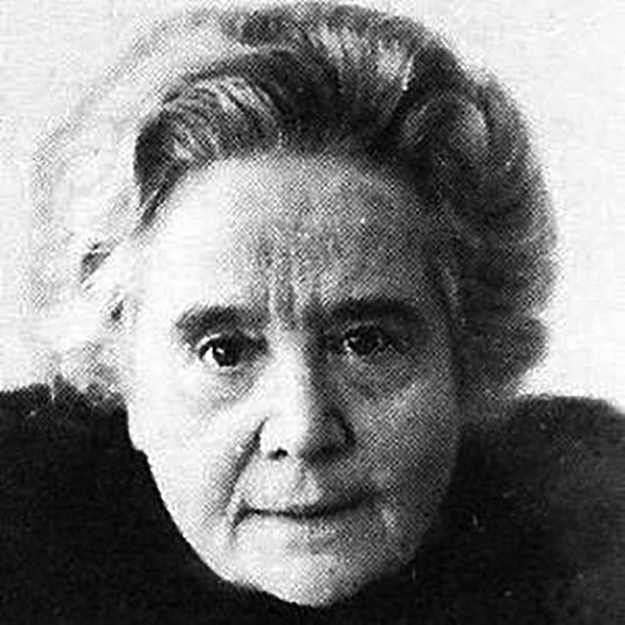

In the Spring 2020 issue of Logos, we are pleased to present in our Reconsiderations feature some of the poetry and prose of Gertrud von le Fort (1876-1971), a German Catholic convert author most famous for The Song at the Scaffold, her novel about the Carmelites of Compiegne who were executed during the French Revolution. A nominee for the Nobel Prize in literature and author of over 20 books whose writings shaped Catholic readers over five decades, le Fort, along with her work, has fallen out of fashion. Literary scholar Helena Tomko argues in her introduction, “’The ‘Golden-Hearted’ Imagination of Gertrud von le Fort,” that the change in reputation had something to do with le Fort’s direct depiction of explicit Catholic themes and the “real nourishment of sacramental life.” In the poetry selected below as in her prose work (also excerpted in the full article), le Fort was direct but not Pollyanna-ish about her depictions of faith from the inside. Tomko introduces us to the place of the poems (written on the cusp of her conversion) in her own work and also their theological and historical significance.

In the Spring 2020 issue of Logos, we are pleased to present in our Reconsiderations feature some of the poetry and prose of Gertrud von le Fort (1876-1971), a German Catholic convert author most famous for The Song at the Scaffold, her novel about the Carmelites of Compiegne who were executed during the French Revolution. A nominee for the Nobel Prize in literature and author of over 20 books whose writings shaped Catholic readers over five decades, le Fort, along with her work, has fallen out of fashion. Literary scholar Helena Tomko argues in her introduction, “’The ‘Golden-Hearted’ Imagination of Gertrud von le Fort,” that the change in reputation had something to do with le Fort’s direct depiction of explicit Catholic themes and the “real nourishment of sacramental life.” In the poetry selected below as in her prose work (also excerpted in the full article), le Fort was direct but not Pollyanna-ish about her depictions of faith from the inside. Tomko introduces us to the place of the poems (written on the cusp of her conversion) in her own work and also their theological and historical significance.

Le Fort regarded the Hymns to the Church as the “true foundation of her writing,” the source from which all her subsequent fiction and verse flowed. The poems record the decisive drama of conversion, but they also marked an extraordinary poetic conversion – a conversion of her poetry but also a conversion through the writing of the poetry. Although intensely personal, le Fort insisted that the cycle of poems exceeded her particular religious experience in their staging of a dialogue between a restless soul and God, who speaks in the voice of the Church. ...

Le Fort’s verse is theologically noteworthy for its depiction of the Church as person. The poet dialogues with the Church, who is unmistakably feminine, spousal and maternal, possessed of an inviolable strength and power of silence, hiddenness and mystery. Although the poet invokes “the Lord” in the prologue, it is the Church who responds in his stead. The poet comes to recognize that the Church undergirds all things in prayer and sacrament: “Should you be silent for a day their light would fail, and were you to cease for a night they would be no more. / Because of you the heavens do not let the round earth fall; all your slanderers draw their life from you” (23). This ecclesial, cosmic vision of the reality of redemption belongs to the same interwar moment in which Guardini was writing powerful apologetic texts like Vom Geiste der Liturgie (1918) and Vom Sinne der Kirche (1922) and renewing popular understanding of the Church as corpus Christi mysticum. In his wartime encyclical Mystici Corporis Christi, Pope Pius XII would use the language of mystical personhood to describe the “unbroken tradition of the Fathers” that “teaches that the Divine Redeemer and the Society which is His Body form but one mystical person, that is to say ... the whole Christ.” Le Fort’s conversion and her poetry find anchor in an ebullient articulation of this “great mystery” of the Church (Eph 5:32), who is as at once Christ’s body and also his bride, the preeminent symbol of whom is his mother Mary. The Church of these poems, as mystical person, is both Christ and theotokos, irreducible to either human institution or the sum of her members’ sins, for whom she prays in perpetual reparation.

Le Fort’s verse is theologically noteworthy for its depiction of the Church as person. The poet dialogues with the Church, who is unmistakably feminine, spousal and maternal, possessed of an inviolable strength and power of silence, hiddenness and mystery. Although the poet invokes “the Lord” in the prologue, it is the Church who responds in his stead. The poet comes to recognize that the Church undergirds all things in prayer and sacrament: “Should you be silent for a day their light would fail, and were you to cease for a night they would be no more. / Because of you the heavens do not let the round earth fall; all your slanderers draw their life from you” (23). This ecclesial, cosmic vision of the reality of redemption belongs to the same interwar moment in which Guardini was writing powerful apologetic texts like Vom Geiste der Liturgie (1918) and Vom Sinne der Kirche (1922) and renewing popular understanding of the Church as corpus Christi mysticum. In his wartime encyclical Mystici Corporis Christi, Pope Pius XII would use the language of mystical personhood to describe the “unbroken tradition of the Fathers” that “teaches that the Divine Redeemer and the Society which is His Body form but one mystical person, that is to say ... the whole Christ.” Le Fort’s conversion and her poetry find anchor in an ebullient articulation of this “great mystery” of the Church (Eph 5:32), who is as at once Christ’s body and also his bride, the preeminent symbol of whom is his mother Mary. The Church of these poems, as mystical person, is both Christ and theotokos, irreducible to either human institution or the sum of her members’ sins, for whom she prays in perpetual reparation.