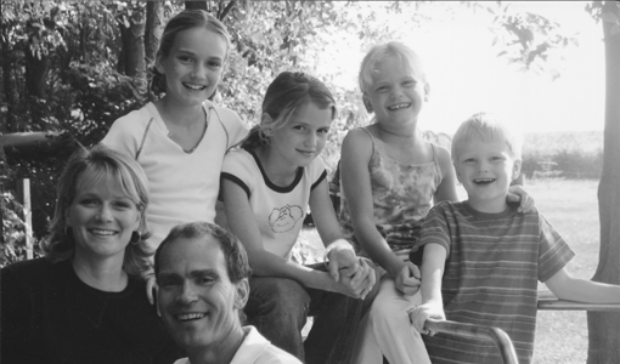

Joanell and Fred Zimmerman: 'Our family benefited by sharing our home and hearts'

“‘Joey’ (not his real name) was about 3 months old when he came to bless our home with his presence. He was very quiet, subdued, not smiling and he avoided eye contact.

“My younger son, who is also fairly quiet, spent time with Joey. He would lie on the floor with Joey as he did his homework. He held Joey while he watched TV and talked to him during the commercials. Most significantly, my son would smile and look into Joey’s eyes until Joey started looking back.

“Then Joey started to smile back and even to make sounds and then more ‘talking’ as if he had always had a lot to say but didn’t know if anyone would listen. Our son listened and nodded and smiled and once in a while gave a brief response. During entire Sunday Masses, our son held Joey. Often people would comment to me after Mass about how they saw the love and connection between our son and the little baby. I thought the bonding was a vital part of Joey’s development.

“The inevitable separation was truly heart wrenching. I believe that babies – and other people – can bond more than once and with more than one person. I hope and pray that Joey has found someone else who loves him and who will look and listen.”

This is how Joanell and Dr. Fred Zimmerman remember one of the 85 foster children they have cared for over 16 years. Joanell is a College of St. Catherine graduate who has a master’s in social work from the University of Minnesota. Fred, the first faculty member in engineering at St. Thomas and the program’s director from 1985 to 1995, will retire in December. They have been married for 43 years, and they have five children.

The Zimmermans provided emergency shelter foster care that required being on call and taking children on very short notice. Fred said his specialties were rocking, reading or giving a bottle, but “the work was done almost totally by my wife, Joanell. Our two youngest, Brigitte and Hans, also helped out very appreciably.

“I believe we all benefited but we do not deserve credit,” he added with typical matter-of-fact humility. “God has a lot of people doing important work.”

The most common reasons for shelter placements are abuse, neglect or abandonment. There are a few voluntary placements, and sometimes a parent has to be hospitalized or incarcerated. Emergency Shelter Foster Care placements are intended to be up to 30 days, with the child either returned to parent(s), placed with a relative, put in long-term foster care or cared for in another way. The Zimmermans had children for as short a time as one day and as long as seven and one-half months; most of them stayed longer than 30 days.

It was not always easy. For less than a year, the Zimmermans took in teenage moms and babies. “The mother was supposed to provide physical and emotional care for her baby and I was to make suggestions and intervene, if necessary,” Joanell explained. “This proved difficult, such as waking the mom during the night to try to get her to feed the crying baby. There were too many stressful situations for me to continue with teen moms. I always thought these moms loved their babies but they were, after all, children themselves.”

Licensed foster parents must meet strict guidelines, including training, background checks and home study, and must have at least a two-bedroom home and a sufficient income for themselves and their family. Families are not paid for their time but are compensated for food and clothing. There are regular monthly support meetings with foster parents, and licensing workers make home visits. Medical care usually is provided through a county or state program. In emergency foster care, the primary caregiver must be a stay-at-home parent.

“Extended family members were involved on holidays and sometimes on other social gatherings during the year,” Joanell said. “I was lucky that my sister also provided foster care. We sometimes got together with our combined children for play dates that included swimming, sliding or other fun.

“Many of the children who came to our home had not been treated very well so transition was usually easy,” Joanell said. “Each child was given a stuffed animal to hold that first night with us and to keep. The children were fed, comforted and provided with a quiet and safe room with a comfortable, clean bed or crib. They typically seemed very grateful for the opportunity to sleep.

“If they cried or seemed fearful, they were rocked, reassured, read to, given a snack or anything else that I could do to help them know that our home was a safe place where someone was available to take care of them. There was nothing heroic; rather, it involved providing the basics that every child deserves to meet his or her common needs, including security.

“Transition out of our home was more difficult. Many children, ages 4 and older, seemed to know the routine as if they had been bounced around often in their short lives. Many of the babies and toddlers cried when they left and this was heartbreaking. The first years when we provided shelter care, the children could be moved on just an hour or two notice. This made the transition very difficult for everyone.

“I remember my birth daughter coming home from first or second grade and, instead of being greeted by a toddler with outstretched arms, she learned that her foster sister had been transferred. My daughter cried and said, ‘I didn’t even get to say goodbye.’ ” Eventually, at the request of several families providing shelter care, the policy of transferring a child included 24-hour notice.

“Then we could sit in a rocking chair, talk about what would happen the next day and say our goodbyes,” Joanell said. “I wasn’t always sure the very young babies understood all of the words, but I’ve always believed that babies understand more than we realize. I also believe that the assurances that I would always value them, care about them and pray for them were conveyed. I so hoped that at the core of their being they would always know they were loved.

“Some of these wonderful little children cried when they were put in the car seat to go with a social worker or case aide. People asked me how I could ever give them up. When a child came, I would remind myself ‘In every hello, there is a goodbye.’ Well, that didn’t actually help that much. Praying did. I asked God to hold her or him in the palm of His hand.”

Sometimes Joanell wondered how this was affecting her birth children. “As young children and even as teenagers, there were often tears when an especially cute and fun (most of them were in this category) foster sister or brother was moved from our home. ‘Please adopt just this one, Mom,’ they would ask. I tried to explain that I had five birth children to raise and educate and I was too old to make the 18-year-plus commitment required. My explanations fell on deaf ears. I remember my younger two children, at ages 12 and 14 saying, ‘We’re already raised!’ ‘Right,’ I thought to myself.

“I concluded that my birth children definitely benefited in many ways from having foster children in our family. They were able to give and receive love, especially from the foster sisters and brothers who were younger than themselves.

“One Christmas, we had four foster children (ages 1, 3, and two were 4 year-olds) with us, plus our younger two and three home from college. Our 10-year-old, Brigitte, said it was the most wonderful Christmas she ever had, buying gifts for the children who were expecting nothing; they were elated at getting new clothes and toys.”

Brigitte, a recent graduate of Stanford University, said, “Doing foster care was wonderful for our family. It bonded us, taught us responsibility, and enabled us to do something for our community as well as for the individual children in our care. More important, being a foster sibling made me so much more grateful for my blessings of a stable family environment and for the unconditional love I received. I also am more aware of the issues faced by families in circumstances that are different from mine, of the problems caused by the inadequacies of our society, and of the importance of remaining open-minded and loving to those who seem troubled, irresponsible or simply different. I definitely will be a foster parent someday.”

Joanell regrets that “we are not allowed to keep in touch with our foster children after they leave. In a couple of cases, the adoptive parents would call or send a Christmas card with an update. These messages were greatly appreciated. I often wonder about this baby or that child and then say a prayer for that specific missed one.”

Really, Fred says, foster care is done for a simple reason. “I was always amazed at how resourceful so many of these children were. Over the years we housed children with a wide variety of problems involving illness, mental difficulties, violence, family disintegration and other problems. One can only conclude that there – but by the grace of God – go I.

“I hope this story can be a selling job for more people becoming involved with helping children. We all need to do our part.”

Amy and Mark Etzell: ‘We approach foster care as if we’re taking care of our brother’s or sister’s kids’

“We love the many insightful quotes of Mother Teresa. She once said ‘the very fact that God has placed a certain soul in our way is a sign that God wants us to do something for him or her. It is not chance. It has been planned by God. We are bound by conscience to help him or her.’

“We think we all need to keep our eyes and hearts open for the chance to help another person,” said Mark ’84 and Amy Machacek Etzell ’91 when they were honored during the 1999 St. Thomas Day celebration as the Humanitarians of the Year. The St. Thomas award recognizes the contributions of alumni to the betterment of the spiritual and material welfare of the less fortunate.

Mark and Amy are parents who have lived with and loved more than 70 foster children. They’ve gotten pretty good at raising children – with love and care.

Over the last 11 years, the Etzells have cared for 72 foster children, ranging in age from 10 months to 19 years. They have had many sibling groups and many single children. They have four biological children, ages 6 to 12, who wholeheartedly accept the foster children.

“When Social Services asks us to take new foster children, we talk to our children about the possibility of adding another child to our home,” Amy explained. “Our children usually say things like ‘these kids need a family to live with, so we should let them come here’ or ‘tell them (the county) that we have room at our house for the kids.’ ”

Mark and Amy are continually humbled by the willingness of their children to accept the foster children. They have shared their toys, their family and their parents with these kids their entire life.

“When we first got into foster care, we kept going back to the passage in the Bible about feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, sheltering the homeless, and inviting in the stranger,” Amy said. “We thought, ‘Isn’t that exactly what we should be doing?’” The couple’s friend, Bishop Paul Dudley, was quick to point out “don’t forget that Joseph was a foster dad, too.”

The Etzell household is generally filled with six or seven children, and the length of stay varies for every child. “Our first foster child came for the weekend and stayed three years,” Mark recalled.

For many children, the stay is never long enough, according to Mark. “Four years ago, we had three brothers, ages 7, 6 and 4, in our care for three years. We thought very hard about adopting them. It was an agonizing decision, but we decided not to pursue permanent placement with them. We were so happy when they were adopted by a great family just six miles from our home.”

There are some heartbreaking stories, as Mark recalls: “A few years ago we had a 6-year-old child placed with us who was found waiting in a truck at a casino for hours while her mom and the mom’s boyfriend gambled inside. The police brought her to our county because it was the last known address of the transient mother.

“We initially thought the families would stay in touch with us after care ended, but soon realized that most families do not want to keep that chapter of their lives open. We do, however, stay in touch with the children who have gone on to adopted families. We also see some of the kids who were with us years ago who are now adults.”

So just how do parents balance life with six or seven children? They have seemingly endless energy; both are very involved in their community. Mark, who majored in physics and math at St. Thomas, teaches community education in Northfield, is a firefighter and is active in the Knights of Columbus. Amy, a psychology major, teaches yoga and fitness classes, and she’s a triathlete and a marathon runner.

Amy’s family lives nearby and is very involved. Her parents have been known by 70 foster kids as Grandma Jeannie and Grandpa John who always remember the foster children on their birthdays and holidays.

Amy’s younger sister, Allie Machacek (now a junior at St. Thomas), was their main babysitter throughout her high school years. Amy has a great deal of respect for her younger sister: “She was the only babysitter who could handle seven kids ages 2 to 8 alone!”

All of the Etzell’s foster children have been on medical assistance but dental care can be difficult to find. The Etzells are fortunate to have a close family friend who is their dentist, and his clinic has taken all of their foster children as patients.

Amy explains that, while it’s difficult to let the foster children go, they established a coping mechanism at the very beginning: “We’ve always approached our foster children as if we’re taking care of our sister’s or brother’s kids. We care for them while they’re here, then they go away. It is certainly challenging when they leave, but this is the mindset we’ve always had. This is someone else’s child, we’ve been asked to care for him or her, and someday it will end.”