Editor's Note: This story is part of an ongoing set of features of student-athlete Kyle Reid, which are the result of nearly one year of reporting on a unique student and his experience at St. Thomas. With so many elements to Reid’s story – as well as the complex and sensitive nature of many of them – we knew capturing everything in a single story would be a difficult task. Our profile of Reid for St. Thomas magazine is the product of those efforts, but due to spatial constraints we couldn’t dig as deeply as we would have liked for certain aspects of Reid’s story. With the goal in mind of providing more detail in some of those key areas, we are publishing these supplemental features in the Newsroom. To read our original story, click here.

Kyle and Andee Reid strolled into an aerobic room in the Anderson Athletic and Recreation Complex (AARC) on a Wednesday afternoon in July, Kyle in a blue Under Armour T-shirt, blue shorts and red-and-white Nike tennis shoes, Andee in a pink “Unleash the Beast” T-shirt, gray leggings and tie-dye shoes. They hooked an iPod into the room’s sound system and – as the beat’s bass began to throb against the floors and mirrors – started jumping rope.

Physical activity long has been a "saving grace" for Reid, a 2011 Afghanistan veteran, and current junior and member of the diving team at St. Thomas. He has struggled to cope with post-traumatic stress disorder and conversion disorder since his return from overseas.

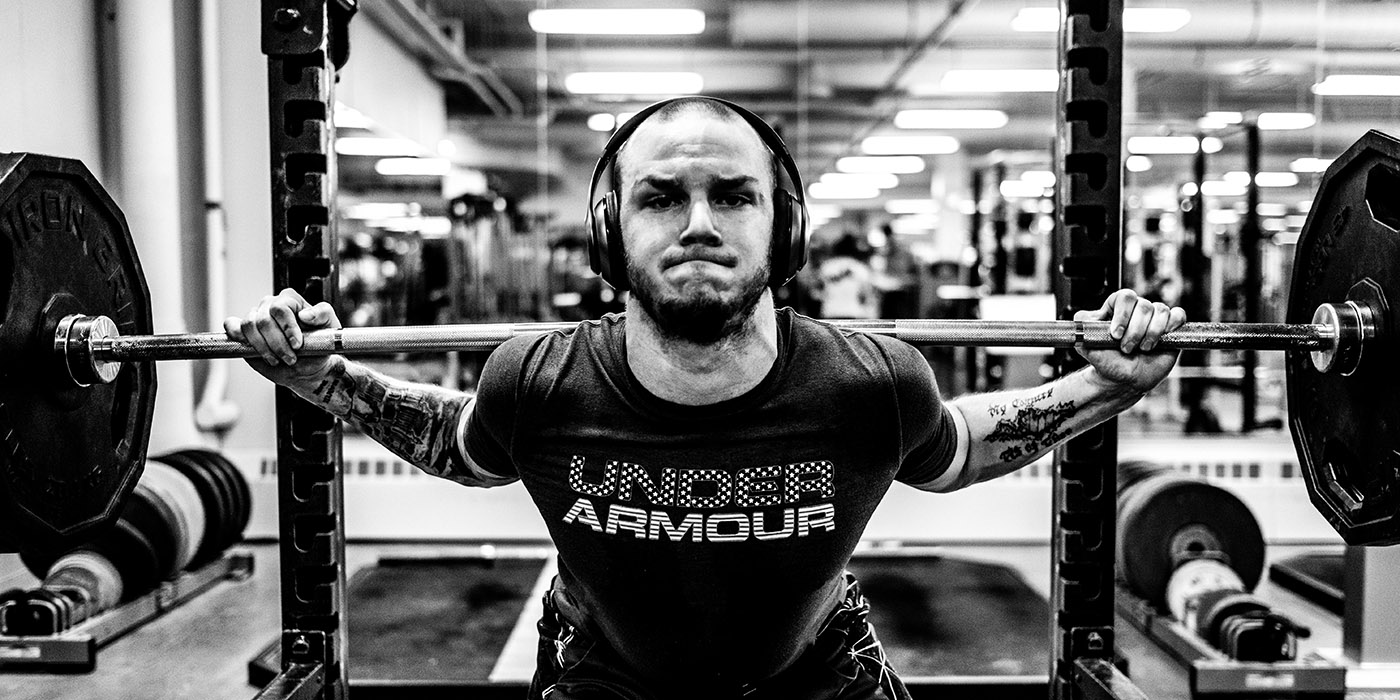

“When I’m lifting or working out I just focus on what I’m doing and don’t really think about too much else,” Reid said. “It takes my mind off of things and internally I reduce my own stress.”

To spend time with Reid as he works out is to see a body relax even as its muscles flex and swell with effort, to see eyes straining with focus and to see a partnership flourishing under the demands of added weight.

Kyle and Andee Reid slap hands following a set of squats.

Reid does box jumps while wearing a weighted vest.

Reid has built workout plans for the St. Thomas diving team since November 2015, and is studying in the Health and Human Performance Department with plans of eventually becoming a personal trainer, specifically helping veterans.

"I can’t say enough about him as a student. He has been a lot of fun to work with," said Reid's academic adviser, Brett Bruininks. "I was unsure when we got him, coming back to school as a transfer [from Montana State University], how much we would have to accommodate him because of transfer credits, visits with the [Veterans Affairs] but he is an on the ball man. Some of the things he’s been through in his lifetime, the fact he’s doing what he’s doing? Wow."

This day in the AARC provided a one-on-one opportunity with his wife, Andee, to practice being a personal trainer.

“Come on, now, that’s two, just one more,” he encouraged as she rose from another squat. “Yes!”

His eyes lit up and he pumped his fist as she racked the weight after a final rep. Matching smiles flashed across their faces as Andee stepped away from the bar. It was an interesting dynamic for the pair: Reid spotting Andee and making sure she’s OK with the weight pressing down on her shoulders. The rest of their lives are the inverse, with Andee omnipresent as a wife and full-time caregiver making sure he’s emotionally, physically and mentally OK at any given moment.

These workouts are a crucial part of Reid staying OK; he learned a long time ago his well-being is impacted directly by his physical fitness. His PTSD symptoms, including hallucinations, haven’t necessarily improved since he returned from Afghanistan, but his ability to cope with them clearly has benefited from including physical activity in his day-to-day life.

“It has helped increase my overall view of life,” Reid said. “It doesn’t only improve my mental health but also, obviously, my physical health.”

Reid's pursuit of physical challenges isn't limited to working out in the AARC. In June 2016 he competed in the Spartan Race, a course of 20 obstacles spread over more than 3 miles of hilly terrain.

Reid and Andee schedule every day in the summer around working out, and even during the busier school year not going to the gym is rare. Those exceptions come almost exclusively from times when Reid's in particularly bad shape mentally; sometimes he just knows he needs to go home and rest, he said. Otherwise, the consistency of his dedication to staying physically active is simply a way of life, every day.

“Whenever you go down there you can’t help but be inspired,” said Bruininks, a former Division I athlete himself. “You can’t help but go, ‘Wow.’ He sees the influence of exercise, weight lifting, the benefits for him, and he’s found a great balance of competition, being a husband, professional and student.”

Sharing those benefits is incredibly important to Reid, and St. Thomas has proven to be the perfect practice grounds for doing just that. Along with stepping into a leadership role by planning and overseeing workouts with his teammates, Reid trained his diving coach, Mark Dusbabek, over several months and helped him drop 20 pounds.

“I had no idea what I was getting into last January when I said yes to [training with] him,” Dusbabek said. “But he does it right. He does it right by his teammates … and that’s the Marine in him.”

During his own workouts, Reid's face and body transform: visible signals of the process he later describes as his mind concentrating on the task at hand and shutting down thoughts about anything else. Joy and physical exhaustion seem to go hand in hand as he works through his full routine and narrows in on the feeling of accomplishment that leaves him feeling good about himself.

Like almost every workout, this particular day he eventually strapped on a weighted vest to give his body that much more to handle. When that extra physical weight comes off, the extra emotional and mental weight of everything he deals with comes right in to replace it.

“There’s about two hours of the day dedicated to working out. Forty-five minutes for cardio and core, the rest for lifting,” he said. “That leaves about 22 hours to fill.”

Reid collapses with a smile on his face following a workout.

Read more from St. Thomas magazine.