A popular place for undergraduates on a sticky August afternoon in St. Paul might be the trails near the Mississippi River at Hidden Falls or the shady parks around Lake Como. But a summer stroll into Owens Science Hall finds a group of students contemplating some of the deepest mysteries of life: Is the mind separate from the physical structure of the brain? How are memories formed and forgotten? What happens during sleep? These students are not idly musing about such matters; these are neuroscience students, working in laboratories using modern scientific tools to explore how the brain controls thought, learning and behavior.

Questions of how the nervous system influences human behavior can be traced to 3,000 years B.C., when an Egyptian surgeon noticed that soldiers suffering particular head injuries displayed specific kinds of behavioral changes. Nearly 2,500 years later, Hippocrates taught that the brain was the origin of all intellect and emotions. But without the ability to directly observe its complex inner workings, medieval physicians and philosophers discounted the impact of the brain, and attributed thoughts and emotions to other internal organs. Depression, for instance, was said to be caused by an excess of black bile in the liver. This perspective was highly influential, and it persists in some aspects of the modern world, where a Valentine’s Day card evokes feelings of love by showing a heart, rather than a brain.

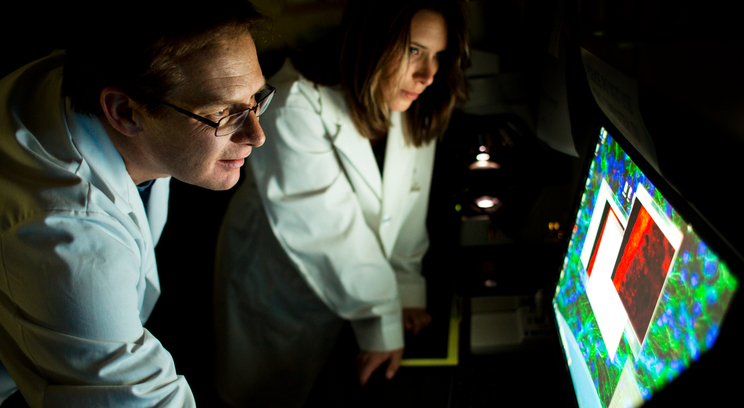

Although philosophers, poets and playwrights through the centuries could draw upon introspection to gain insight into the mind, the scientific study of the brain was not possible until technology helped to solve key mysteries of its fundamental nature. At the turn of the 20th century, a few scientists applied techniques borrowed from photography, electricity and biology to carefully study the brain and nervous system. Further technological breakthroughs in physics, chemistry and computing during the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s allowed nerve cells and brain circuits to be examined directly, and the seeds of neuroscience were planted.

True to these roots, modern neuroscientists approach some of the most intriguing questions in biology and human behavior from a wide range of perspectives. Neuroscience is an interdisciplinary endeavor in which scientists weave webs of collaboration through seemingly distant fields. Molecular biologists who study DNA collaborate with psychologists who use carefully crafted behavioral experiments to explore how genes affect memories. Even the Dalai Lama has paired with functional anatomists to help investigate how meditation impacts the brain. Such a wide range of perspectives and collaborations can bring about insights into human thought and behavior that would not have been possible a decade ago; however, this complexity also can make neuroscience a difficult subject for undergraduates to explore.

Evolution and Growth

At the University of St. Thomas, undergraduate study in neuroscience can trace its origins to a “behavioral neuroscience” concentration first offered by the Psychology Department in 1990; however, this early program did not reflect the interdisciplinary nature of modern neuroscience. As psychology professor Roxanne Prichard noted, “The major did not require much biology, chemistry or advanced math.” Upon being hired in 2006, one of Prichard’s first tasks was to make sure the program addressed the breadth of the field and prepared students to compete for positions in top neuroscience graduate programs. The result was the creation of a new interdisciplinary Program in Neuroscience, jointly administered by the Biology and Psychology departments. The program began in 2008, offering a bachelor of science degree in neuroscience. Three faculty members were officially affiliated with the fledgling program, and one student graduated with a neuroscience major that year.

The low initial numbers masked tremendous growth the program would soon face. Two more faculty members were hired in 2009 (one each in biology and psychology), and as word spread about the new program, it quickly gained popularity for its interdisciplinary approach. Sibel Dikmen, now a senior, recalled being attracted to the program her freshman year: “I liked that the neuroscience major adds diversity to the sciences. From an educational standpoint, the Neuroscience Program forced me to broaden my horizons.”

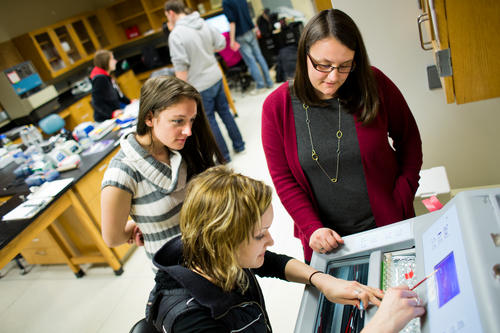

A student works with a microscopic section of brain tissue at a Cryostat machine during a neuroscience class. (Photo by Mark Brown)

Evan Eid, a 2010 graduate who is now a researcher with the Environmental Protection Agency in Duluth, Minn., said the Neuroscience Program provided him with the motivation and focus to complete his studies. “When I heard about the neuroscience major, I jumped at the opportunity. Neuroscience opened up such a fascinating world for me,” Eid said. “I saw my professors’ passion for the subject and that really motivated me to try harder.”

Appealing to a group of students whose interests span traditional disciplines, the program now counts more than 200 degree-seeking students, making neuroscience the university’s largest interdisciplinary program and one of the most popular majors in the College of Arts and Sciences.

In response to this rapid growth, several changes were made to the Neuroscience Program. In 2012, the faculty approved a new structure for the major that brings more cohesion to a body of interdisciplinary coursework that might otherwise feel disconnected. This curricular overhaul also added eight new courses to the neuroscience major that strengthen the program by helping students unify their foundational coursework in biology, chemistry, math and psychology within the framework of neuroscience. The breadth of coursework might seem overwhelming, but Prichard sees it as a clear advantage, particularly for students interested in the health professions. “The program has really given students more choice in their course plan,” she said. “Many students are interested in the body and human health not just from a biological standpoint but also from chemical and psychological perspectives. The Neuroscience Program exposes students to multiple ways of investigation and problem solving.”

Students agree. Adam Wieckert, a senior who transferred to the University of St. Thomas after learning about the Neuroscience Program, said, “The program adds an interdisciplinary approach to understanding life. I think the program is headed in the right direction.”

The rapid increase in numbers of students and courses has raised some challenges. Almost immediately, the Biology and Psychology departments had to hire several new faculty members to support the program. For these newly hired professors, the Neuroscience Program was a significant reason for joining the College of Arts and Sciences. Sarah Heimovics, a behavioral neuroendocrinologist hired by the Biology Department in 2012, was particularly attracted by the opportunity to help build a strong Neuroscience Program. “I was thrilled to join a university where student interest in neuroscience has grown,” she said. “There is a community of faculty trained in the neurosciences, there is strong support for the program at the administrative level, and there is a large pool of bright, motivated students. These are the primary reasons why I accepted a position here.”

The Neuroscience Program also attracted Sarah Hankerson, a behavioral ecologist who joined the Psychology Department in 2012. “The presence of the program and the strong support by the administration showed a lasting commitment to interdisciplinary education,” she said. “It also demonstrated the ability of the university to adapt to the rapidly changing face of science.” Hankerson, whose own work encompasses both biology and psychology, pointed out the value of this interdisciplinary approach: “Our students gain an understanding of how biological processes impact our daily lives, social interactions and mental health. Being a part of the Neuroscience Program allows me to fully embrace the interdisciplinary nature of my work.”

The College of Arts and Sciences faculty affiliated with the Neuroscience Program reflect the diversity in modern neuroscience. For example, Heimovics might be out in the field observing birds one day and in the lab looking at neurons under a microscope the next. Students benefit from this diversity in approach. As Heimovics remarked, “Moving forward, our students will understand the nervous system at multiple levels of analysis, making them better prepared and more competitive in their chosen careers.”

Making Connections Through Student-Faculty Research

As a result of recent hiring, 10 faculty members from the Biology and Psychology departments are now associated with the Neuroscience Program, and it is an active group. These professors conduct cutting-edge research, attract external scientific funding and publish their work in prestigious scientific journals. But most importantly, these faculty members are committed to involving undergraduate students at every stage of their research programs. Each year, dozens of undergraduate students gain research experience by working alongside professors in labs and during field studies. These opportunities give students the chance to experience modern neuroscience as it happens, often in the role of a scientific colleague. Jadin Jackson, a computational neurophysiologist who joined the Biology Department in 2011, emphasized the quality of these experiences: “The laboratory experience that students gain is on par with specialized graduate student workshops offered at the national and international level. Students gain hands-on experience with neuroscience techniques that deeply enhance and enrich the topics covered in the classroom.”

Professor Sarah Heimovics, right, works with student Carissa Libbenga and St. Catherine University student Margaret Miller (standing, left), at a Cryostat machine during a neuroscience class. (Photo by Mark Brown)

In addition, some students earn competitive research grants awarded by the University of St. Thomas to conduct their own projects in collaboration with a professor. Chloe Lawyer, a junior who conducts research in neuroscience, has experienced all aspects of scientific projects. But when she started, she wasn’t sure she was interested in research. “When I started working in the lab, I was uncertain about my future,” she said. Lawyer began working on a project in Kurt Illig’s lab in the Biology Department, investigating whether the chemical dopamine impacts memory formation in the brain. Dopamine is widely known as the neurotransmitter that is activated during pleasurable events, like eating chocolate.

Dopamine also is activated by drugs of abuse such as cocaine, and this activation may be the reason such drugs are addictive. After working on this project, Lawyer’s uncertainty cleared. “I quickly realized that I had a passion for research,” she said. Lawyer continued to collaborate with her professor to conduct experiments to discover how the dopamine system changed during adolescence. With experience on two projects, she was ready to design and carry out experiments of her own that would help determine whether the changes in the dopamine system during adolescence might contribute to the prevalence of drug addiction in teenagers.

Working with two other undergraduate students in the lab, Lawyer examined the brains of developing laboratory rats, which are used as a model for human brain development. The students started out by looking at the levels of dopamine receptors – the part of a neuron that receives messages from other cells – and found that these levels were low in juvenile and adult rats, but were very high during adolescence. Genes that encode these receptors were activated more during this time, too. But did this spike in receptor levels have any behavioral relevance? To complete this project, the students conducted two more sets of experiments. In the first, they showed that adolescent rats had a more difficult time learning new information than juvenile or adult animals. In the second, they showed that learning in adolescent rats could be improved by using low doses of drugs that specifically target the activity of dopamine receptors. Finally, in February 2013, the paper detailing their work was published in the high-profile, peer-reviewed scientific journal PLoS One. Lawyer and the two other undergraduates are co-authors on the study.

The project took almost two years to complete, but the hard work paid off in a number of ways. Lawyer reflected, “Research has allowed me to form close relationships with the faculty at St. Thomas, and also has connected me with neuroscientists throughout the country.” Neuroscience students make these connections by presenting their findings at national and international meetings, including the Society for Neuroscience and the Association for Chemoreception Sciences conferences. Lawyer plans to use these connections next year as she begins to identify programs where she can pursue a Ph.D. in neuroscience, but she said the experience has been about more than networking: “Most of all, it has been an incredible learning experience, and the St. Thomas faculty do a fantastic job at developing students’ skills as researchers.”

Betsy Smith, a junior neuroscience major, also conducts independent laboratory research. She said this has been her best experience at the University of St. Thomas. “It is an incredible opportunity that has allowed me to learn more than I would have in a classroom alone. The collaborative student-faculty research programs are unique because they focus on students being the primary investigators in the lab, allowing them to explore their own interests.”

By working closely with professors on innovative research, students learn how to critically analyze problems and pursue innovative solutions with modern scientific tools. Many recent graduates of the Neuroscience Program have continued their education in medical, dental and graduate schools. Brittni Peterson, a 2010 graduate and co-author on the PLoS One study, is now a Ph.D. student in neuroscience at the University of Minnesota. She credits the research experience she had as an undergraduate with helping her find her career path. “The research experience at St. Thomas is exquisite, because it allows for direct, one-on-one interactions between students and faculty,” she said. “At a larger university such as the University of Minnesota, it is uncommon to have these close interactions. I would not be where I am today without the St. Thomas Neuroscience Program and its faculty members.”

In just five years, the Neuroscience Program has made a positive impact on CAS students. With new courses in the curriculum and a larger, more engaged community of faculty and students, the program is in position to support further collaborative learning; however, new challenges can limit these opportunities. As Prichard said, “We have expanded with new faculty hires, but we really need to expand our teaching and research space to provide a high-quality experience.” Psychology professor Uta Wolfe agreed: “Most of us temporarily set up our projects in shared spaces. More research would get done if rooms could be set up permanently.”

Another challenge is that faculty members in the program are split between two departments that are housed in separate buildings at different locations on the St. Paul campus. This physical separation limits the opportunities to work together to foster cross-disciplinary relationships. As Hankerson said, “A closer connection between departments would enhance our communication and collaboration, both in the classroom and in the lab.” Such enhanced collaboration would lead to more and better opportunities for students; “the closer the connection among faculty, the stronger the program.”

The ongoing challenges and changes facing the Neuroscience Program do not diminish the strength of its approach, however. “The future of the program looks bright,” said Dr. Greg Robinson-Riegler, chair of the Psychology Department. “Interdisciplinary study holds the key to answering the ‘big’ questions, and there really are no bigger questions than the nature of the biological mechanisms underlying consciousness and behavior. The Neuroscience Program puts students on the cutting edge of science. I’m proud that UST is one of only a handful of comparably sized institutions to have a rigorous Neuroscience Program.”

Read more from CAS Spotlight.