They’re not always the most appealing people. Convicted of mostly drug-related crimes, these aren’t the innocent who have been convicted unjustly. They are guilty and they know it, and society thinks they have gotten what they deserve. Justice has been served, and most of us have forgotten about them.

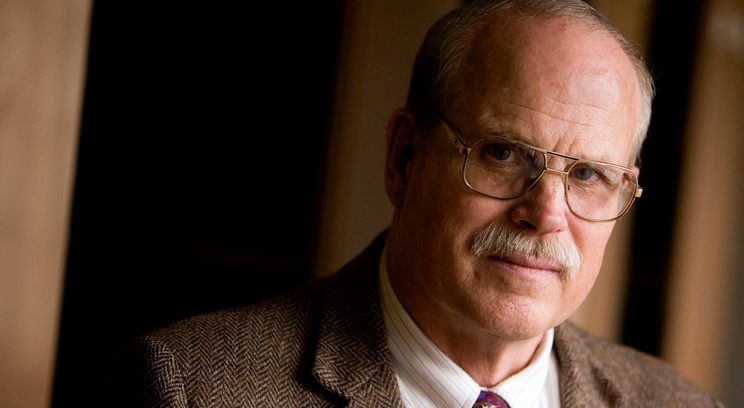

These are the people who write to Mark Osler. A former federal prosecutor turned St. Thomas School of Law professor, Osler is deeply concerned about the harsh sentences handed down for drug crimes, usually related to crack. He has received dozens of letters from people in prison who are looking for someone who can help them make a case for a reduced sentence.

But do they deserve the sentences they have received? Do they deserve a second chance? How can justice and mercy coexist?

A Legal Process Rooted in Mercy

By the early 1980s, crack cocaine had become an enormous problem in the United States. In response, a law was passed requiring that one gram of crack be treated like 100 grams of powder cocaine for sentencing purposes. Decades later, after a U.S. Supreme Court ruling, Congress passed the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, which significantly reduced this disparity.

The rub? The law was not retroactive. Individuals who were sentenced under the old guidelines still serve much longer sentences than they would have if they were sentenced today.

To Osler, it just doesn’t seem right. Certainly the judicial system focuses on justice: people paying the price for what they have done, but there is a place there for mercy – one carved out in the Constitution itself. It is the power of the president to pardon or commute sentences.

So, Osler has been working to gain commutations of these long sentences, “both at the wholesale and retail level,” he said. Wholesale, he’s trying to change the system. Retail, he’s working for the commutation of individual sentences.

Enter St. Thomas’ new Federal Commutations Clinic. Osler founded it in 2011 to meet two needs. The first is to build law students’ storytelling skills. “In this clinic, students learn how to develop a narrative, adding breadth to the story [of their client],” Osler said. And this requires listening – “a deeply important lesson for law students.”

Osler believes storytelling is a critical legal skill for every practice area. “Corporate lawyers have to tell the corporate story,” he said. “And it’s the heart of litigation. If I can get a jury to see the story through the victim’s eyes, the prosecution will probably win the case. If the defense can get the jury to see the case through the defendant’s eyes, they’ll likely win.

“In the end, law is more storytelling than argument,” he said.

In addition, the clinic fulfills the School of Law’s mission, in which the school is “dedicated to integrating faith and reason in the search for truth through a focus on morality and social justice.”

“Commutation is the only legal process that is rooted in mercy – a Christian virtue,” Osler said. “Alexander Hamilton called it mercy when he argued for its inclusion in the Constitution.” In addition, the clinic takes people into places they would never otherwise go to meet people they never would meet any other way. “In the Bible, Jesus talks about visiting the prisoner,” Osler said. “The clinic makes that a present event for these students.”

Caitlin and Debbie, Meet Tadd

Two students involved in the Commutations Clinic last year were Caitlin Karraker and Debbie Walker.

Karraker applied for the Commutations Clinic for a personal reason – family. “Both my parents are nurses in a prison, but they kept their work separate from the family,” she said. “I thought this experience would help me better understand who they are. And I want to be a prosecutor, so the clinic offers great practical experience.”

Walker’s interest stemmed from a desire to gain a fresh perspective on justice. “This clinic showed me how the criminal justice system impacts individuals in a way I couldn’t get anywhere else,” she said. “And it’s so valuable to work with someone like Professor Osler, who has real-life experience in this area. It will equip me with something I’ll use throughout my career.”

Early in the fall, Osler presented several cases for the clinic students to consider. He already had eliminated those he knew would not be successful: those in which appeals are pending, for example, or in which the person had broken laws in prison or continued to maintain his or her innocence.

Walker and Karraker ended up with the case of Tadd Vassell, a first-generation Jamaican-American from the Bronx. Growing up in a single-parent household, he became involved with a group of much older males and started selling drugs. When he was 18, Vassell and 12 other men were arrested on drug-related offenses, and his sentence added up to life behind bars.

Once they had their case, Walker and Karraker drew up a retainer agreement, and dove into research. They connected with Vassell, his family and friends, and learned all they could about the case and the man.

Vassell was serving time at the U.S. Penitentiary Hazelton, a high-security federal prison in West Virginia, and Karraker had been trying for months to arrange a visit. She submitted the background forms so she and Walker could be added to the visitors’ list. But no one would answer the phone, and she received no response to emails or voicemails.

So Walker and Karraker left Minneapolis for West Virginia, not knowing if they would even be able to see Vassell. While driving through Ohio, Karraker finally connected with someone at the prison. She learned that they could not have a private “legal visit,” because those must be requested two weeks in advance. It didn’t matter that she had been trying to request such a visit for two months. Regular visits are limited to Fridays and Saturdays. Fortunately, the pair was in West Virginia on a Friday and Saturday, or they would not have been able to see Vassell at all.

“It was crazy,” Walker said. “We had no privacy, and we could not have paper or pencil. I was trying so hard to remember everything that was said. One visit lasted five hours, and afterward, we wrote furiously in the car, trying to get everything down.”

“I really thought I’d be able to talk my way into a legal visit, but they just laughed,” Walker said. “Figuring out how to work within the prison system is a big part of what we learn in this clinic.”

Karraker added, “And it gives me such empathy for the families. Every prison is different – it must be so frustrating to deal with them all.”

Walker was responsible for connecting with Vassell’s support system. He remains close to his friends and family, who have visited him in all five prisons in which he has been incarcerated – a rarity. This network of support has “given him a sense that he’s part of life outside,” Walker said. “Knowing your whole world isn’t inside prison walls helps keep you engaged and growing.”

And he has friends – even one he made while in prison. Cathryn Marchman learned about Vassell’s case through his uncle, and they got to know each other by phone and email. It was more than two years before they met face to face. Now they are fast friends, and Marchman has worked tirelessly to right what she sees as the injustice of his sentence. She, in fact, initially wrote to Osler.

Grateful for Support

After the research was done, Walker and Karraker wrote the commutation petition. And now they wait.

But even though a final decision has not yet been handed down, the impact of this case has been far-reaching.

According to Marchman, Vassell was awed by Walker and Karraker’s work on his behalf, and their care for him. “He was so touched, especially when they drove down to see him,” she said. “His gratitude for their efforts really keeps him going. This is what motivates him to help others, and to keep from falling into negativity.”

By email, Vassell said that when he learned Karraker and Walker would be working on his case, “I was elated and felt as if God had seen my tears and answered my prayers. It has meant the world to me and my family, but more importantly strengthened my belief in the need for criminal justice reform.” He added, “I will be forever indebted to the University of St. Thomas, Professor Osler, Ms. Walker and Ms. Karraker. Their acts of kindness not only renewed my faith in humanity, but also strengthened my resolve to become a vessel for change in the lives of those I am around.”

Marchman also found it comforting to know that others were working on Vassell’s behalf. “I’ve been waving this flag by myself for a long time,” she said. “Knowing Tadd and I weren’t alone in this endeavor was so encouraging. And knowing that Debbie and Caitlin were working with Professor Osler, so we could get his expertise involved in the process as well, was just amazing.”

Karraker went into this experience hoping to see how the criminal justice system plays out from top to bottom, and she learned more than she hoped for. “I have a much greater understanding of the impact of our justice system on individual people,” she said. “I worked in a prosecutor’s office last summer, and I understood in a whole new way that a prosecutor’s initial decision will impact someone’s entire life. I tended to want to be more merciful or compassionate. My boss kept telling me I should be harsher, and make fewer plea agreements.”

For Walker, the personal and professional changes can’t be separated. “My compassion grew,” she said. “Like most people who come to law school, I had a keen sense of what is and isn’t just. But it’s so different when you see somebody with a life sentence that is technically fair. It’s one thing to discuss theoretically in class what people deserve, and quite another thing to sit down with someone who’s been on the receiving end of a sentence.”

She also found great value in learning to tell the story. “Every case and every person has a story,” she said. “One of the problems with the justice system is that it’s more like an equation and doesn’t take circumstances into account. If you tell a narrative, you’re better able to take the whole person into account.”

It’s those stories that can change lives.

Read more from St. Thomas Lawyer.