In fall 1956, I was 18 years old and attending the then all-male College of St. Thomas. My freshman class was composed of recent high school graduates as well as a number of Korean War veterans. These young men were in their 20s and had seen the world. They had experienced the horrors of war – fear, destruction, deaths and dismemberment. I admired them with their heavy beards and crew cut hair; they were older, more mature and not given to suffer fools gladly.

Every Friday at 9 a.m. the freshmen class, which consisted of approximately 500 students, was required to attend an hour-long convocation in the small auditorium – an obligation that was obeyed with less than little enthusiasm. No one wanted to be there; however, what occurred one beautiful autumn morning is something that I will never forget.

The speaker’s topic for the day was “The Evils of Smoking,” a topic no one talked about in the 1950s when everyone on television and in the movies smoked and when magazines and billboards extolled the pleasures (and sexiness) of cigarettes. His opening remarks were greeted with hooting and hollering, which grew louder and louder as younger and older disaffected student voices united in a loud, defiant chorus. Then out came the cigarettes and smoke started to fill the auditorium. Not participating – but not objecting either – I stared in wide-eyed fascination.

The speaker tried to continue but it was impossible to hear what he was saying. He stopped and began again, but the noise grew even louder.

Apparently someone left the auditorium to alert the administration because within minutes the head disciplinarian of the college, the dean of students, arrived. Father Vashro, a balding, gruff man with a hardnosed reputation, ascended the stage and attempted to quiet the crowd. He shouted and gestured at us but the noise grew louder and the smoking continued unabated. After several minutes, a defeated Vashro left fuming and frustrated.

A few moments went by. It was a mob scene the likes of which I had never witnessed in the relatively quiet of Stillwater where I grew up. No one moved from their seats, but the catcalls and the smoking continued. I was frozen in place – waiting, watching and wondering what would happen next.

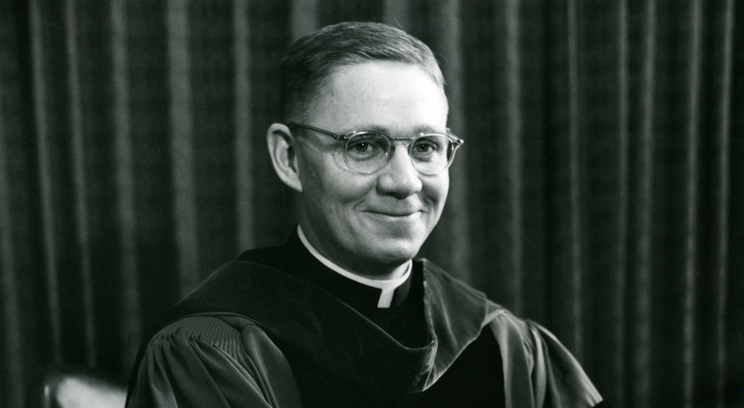

Then, as if out of nowhere, a small, short-haired young man in the black robe of a priest appeared. I recognized him as Father James Shannon, president of the college. Shannon walked to the center of the stage and stopped, looking out at the crowd. He didn’t say a word. He didn’t get behind the speaker’s podium. He just stood there for what seemed like an eternity.

The noise gradually began to recede. Still he made no effort to speak. Finally, it became eerily quiet and still in the room. At last, in a low but steady voice that you had to strain to hear; Shannon said, “Gentlemen, and I know that you are gentlemen, this man has an important message and deserves your respect. You will give him your undivided attention. Thank you.”

And with that, he turned, stepped off the stage and left the auditorium.

The speaker was as stunned as the crowd. He tried to start again but had difficulty getting his voice. The audience remained silent until he finished his shortened message, said “thank you,” and walked out.

When I walked out of the auditorium that crisp fall morning, I knew I had witnessed something very special; something I would remember the rest of my life. This man of the cloth, with the full authority of this all-male Catholic college behind him, had not threatened to invoke a higher power or to bring down the wrath of the college on his unruly students. He had simply asked for nothing more than common courtesy and respect.

These first-year students, many of whom had witnessed the unspeakable atrocities of war and who could not have cared less about the “evils of smoking” or what God or the college could do to them, had listened and understood his appeal for human respect. The power of that message had transformed an unruly mob into a group of silent, chastised young men.

No recriminations, no further mention that I recall, was made of the incident by the college. Even my other 18-year-old friends did not say much about it afterward, but I bet they remember it as vividly as I do.

I still tear up when I think about the power of that message and what it was able to accomplish that day through the appeal of a diminutive cleric in a black cassock who had only to remind us of the importance of individual dignity and common humanity.