John Vachon didn’t intend to be a photographer. When he arrived at the College of St. Thomas in 1931, not far from where he grew up, he harbored ambitions of becoming a writer. He thought about being a priest for a while, too, but that didn’t exactly stick.

John Vachon '35 in 1942. He died at 61 in New York City in 1975.

No, when he graduated in 1935 it was with no intention of contributing tens of thousands of images to documenting American history; he was off on a writing fellowship to Catholic University in Washington, D.C. That didn’t exactly stick, either. After leaving the school he wasn’t about to head back home, though, and he landed a job writing captions on the backs of photos for the Resettlement Administration, which in 1935 had begun compiling a pictorial record of American life. (The Resettlement Administration would go on to become the Farm Security Administration (FSA) in 1937. FSA’s photography unit was rolled into the Office of War Information in 1942.)

Noticing gaps in the developing files, Vachon offered to take photos in his free time on weekends.

Today, a search for “John Vachon” in the Farm Security Administration – Office of War Information Photograph Collection will yield 11,157 images. The volume of his work is staggering, but even so it is difficult to fully appreciate Vachon’s contributions as the longest- tenured photographer of the effort, which boasts some 175,000 total images from 1935-44.

Man and boy crossing the street, Dubuque, Iowa 1940

Commuters waiting for trains, Chicago, July 1941

A gas station attendant wiping off a windshield, Cairo, Illinois, May 1940

Dock worker and his son, New Orleans, March 1943

Vachon also traveled in 1946 to postwar Poland to photograph for the United Nations, and upon returning became a staff photographer for Look magazine, a weekly photo publication. Vachon took countless photos over two-plus decades with the magazine, most notably a days-long shoot with Marilyn Monroe in 1953, which featured the only time Monroe and Joe DiMaggio formally posed together for a photographer.

As he built an incredible library of work, Vachon was fulfilling the goals he articulated while he was at St. Thomas. As he wrote in John Vachon’s America: “I must make it my lot to live, travel and enjoy life. Then, if I don’t rise in the creative eld, I can at least have seen, have read, have been, have lived! All of which is a wonderful lot.”

Vachon did all of that, leaving behind a legacy of capturing American life as only a photographer can. Although his dreams of professional writing never came to fruition, his expansive journaling and many letters to his wife, Penny, as he traveled the country for the FSA show how thoughtful and articulate he was about the purpose of his work.

Ozark children getting mail from RFD box, Missouri, May 1940

Boys in front of drugstore, Dover, Delaware, July 1938

Window shopping, Chicago, Illinois, July 1941

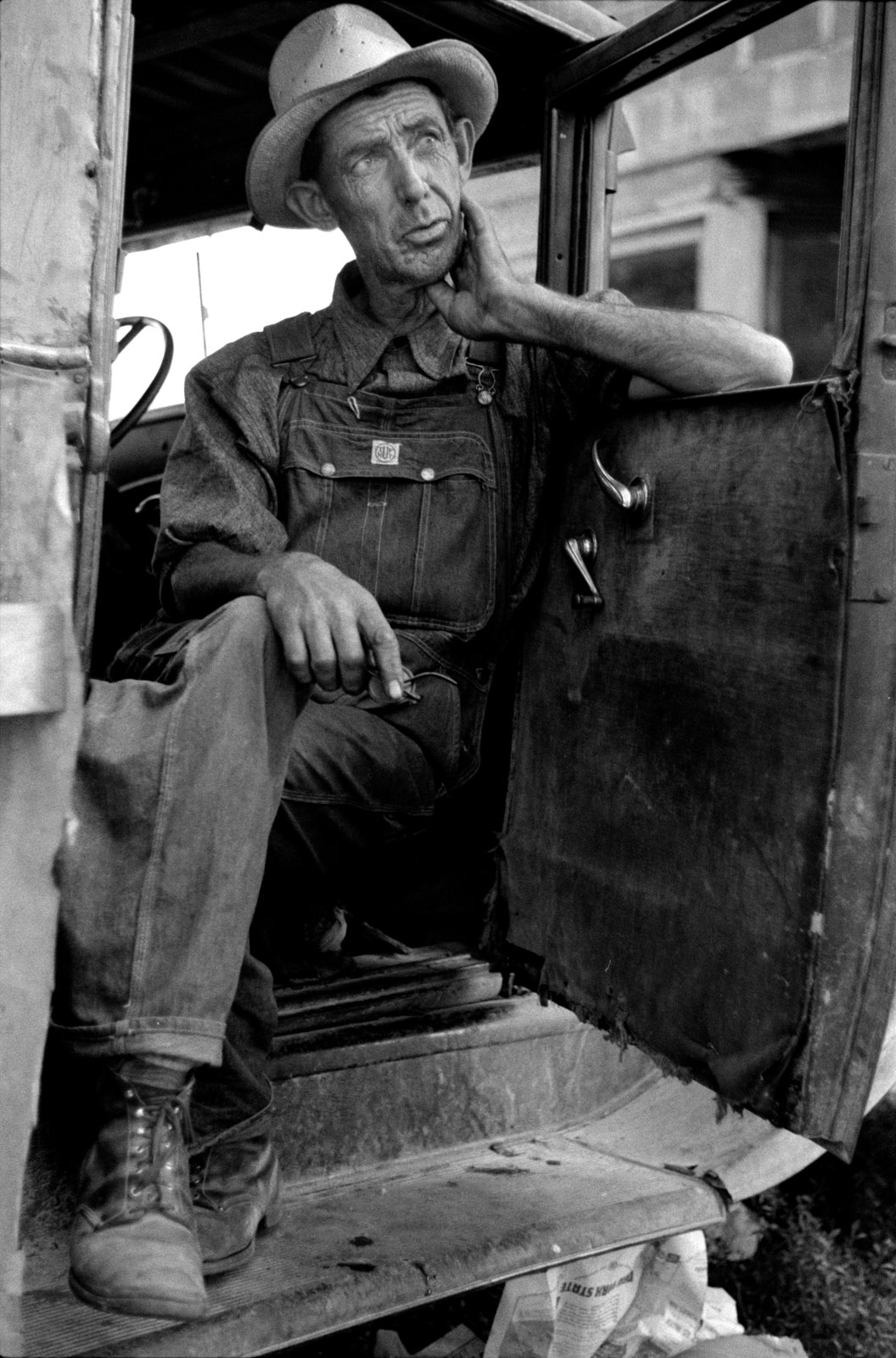

Arkansas farmer after picking fruit in Berrien County, Michigan, July 1940

“The documentary urge is the most civilized manifestation of the instinct for self preservation,” Vachon wrote. About the societal value of the FSA archives, Vachon wrote that its sole purpose should be “the honest presentation and preservation of the American scene. If that is done, it can be drawn upon like dependable statistics to support or refute. If formed only to present, it can be used to propagandize.”

Although never as well known as some fellow photographers such as Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans who also chronicled 1930s America in frames, Vachon’s contributions to that purpose of “honest presentation and preservation” are undeniable and exceptional. Even in black and white, his photos ooze with the details and context that make its viewers believe, “This is the way life was, in this time and this place.”

That spirit lives on at St. Thomas, where communication and journalism students showing promise as photojournalists may receive a Vachon Scholarship. The awards are given on the basis of academic excellence and the strength of their portfolio of work – signs they already may well be on track to follow in Vachon’s footsteps.

Ladies who live in a rooming house, St. Paul, Minnesota, September 1939

Flour mill district, Minneapolis, September 1939

Waiting for the train to Minneapolis, East Dubuque, Illinois, April 1940

Of course, his footsteps weren’t pointed toward photography when he was at St. Thomas; Vachon used to say his becoming a photographer was a happy accident. The man who hired Vachon at the RA, Roy Striker, was looking for qualities in his workers that any Tommie would know the value of after their time here: “Curiosity. It was a desire to know, it was the eye to see the significance around them.”

So it was perhaps no accident at all that brought Vachon to a camera and a purpose. He may have been ready all along.

Read more from St. Thomas magazine.