Robert J. White always was going to work on brains.

Or so it seems.

As a student at DeLaSalle High School in Minneapolis, White elicited high praise from his science teacher – a red-haired Catholic brother – who couldn’t help but notice the preternatural precision with which his young pupil removed a frog’s cranium without so much as nicking the brain beneath it.

White’s teacher took one look at his dissection and declared, “White, you should be a brain surgeon.”

If the priest could have peered into the future, he no doubt would have been wonderstruck by how premonitory his advice had been.

White became a brain surgeon all right. He dedicated his life to exploring and healing this wondrous organ.

Driven to unlock the mysteries of the mammalian brain – the organ that he believed defined humanity and that he famously called “the physical repository of the human soul” – White embarked on a four-decade career that included 10,000 brain operations, regular philosophical consultations with two popes, an invitation to personally examine Vladimir Lenin’s preserved brain, and pioneering research that would earn him respect, renown – and notoriety – the world over.

Bright White

People who are unusually gifted tend to get noticed. Likewise, every step of White’s path to earning his medical degree was paved with well-wishing mentors who ensured his trajectory matched the speed of his learning.

As an elementary student, one of the brothers at White’s school advised him to attend an elite preparatory military academy in St. Paul because he was so academically gifted. But his parents made it clear he would not receive any advantages his brother and cousins didn’t have. White had to decline the academy scholarship.

Instead, in 1941 White’s parents enrolled him at DeLaSalle High School in Minneapolis, where his superior medical skills first drew attention while he was an underclassman and where he graduated first in his class. His daughter Ruth recalled hearing stories of how the DeLaSalle brothers would parade her father through the upper-class rooms – hoping a brush with a genius-level lowerclassman would shame his older peers into studying harder.

Life wasn’t always easy at home. The family grew unexpectedly when White’s aunt Helen and cousins Patrick ’51 and William ’50 Hedrick moved in after an auto accident killed their father. With three adults and four boys (including White’s biological brother Jim ’51 – a pioneering doctor in his own right), money was tight.

When White was just 16, his father – a reservist – was drafted into the war in 1941 and died in a POW camp in the Philippines two years later. With two widows raising four boys, the family’s financial situation worsened.

At 18, shortly after graduating from high school, White was drafted into the military. He became a member of the U.S. Army in 1944 at the tail end of World War II. According to Ruth, “when Army personnel saw his academic record they enlisted him as a lab technician. My father knew from a very young age that he would work in a medical profession,” she said, adding that he began taking medical classes while running experiments and blood tests as a private in the Army. “They only had one patient in his lab most of the time,” she remembered her father telling her. “It was a fully functional lab, but there weren’t a lot of patients because there wasn’t a lot of war activity going on at that point.”

After the war, White attended the College of St. Thomas for three years until 1949 – fully funded through scholarships and the GI Bill. His tenure was cut short one year shy of graduating with a Bachelor of Science degree when a professor suggested he needn’t bother with the formality of an undergraduate degree. He convinced White that his fourth year would be best served in medical school.

In 1950 White enrolled – on a full scholarship – in the nearest medical school, the University of Minnesota, and was there for about a year until a professor took note of his prodigious aptitude for neuroscience and urged him to pursue loftier challenges at Harvard Medical School. White heeded the call, transferring again on a full scholarship.

In 1953, at 27, he graduated with an M.D. He later earned a Ph.D. in neuroscience from the University of Minnesota while spending six years at the Mayo Clinic. (His thesis was on a total hemispherectomy of a dog brain.)

White completed his internship at Peter Bent Brigham and Children’s hospitals in Boston, where he narrowed his field of study to neurosurgery at the encouragement of another mentor. Auspiciously, during his internship, the world’s first successful live organ transplant (a kidney) was performed by Drs. Joseph Murray and David Hume two days before Christmas in 1954.

(For the record, White never officially received a bachelor’s degree, but St. Thomas made it up to him by granting him an honorary Doctor of Science degree in 1998.)

The Head Transplant Heard 'Round the World

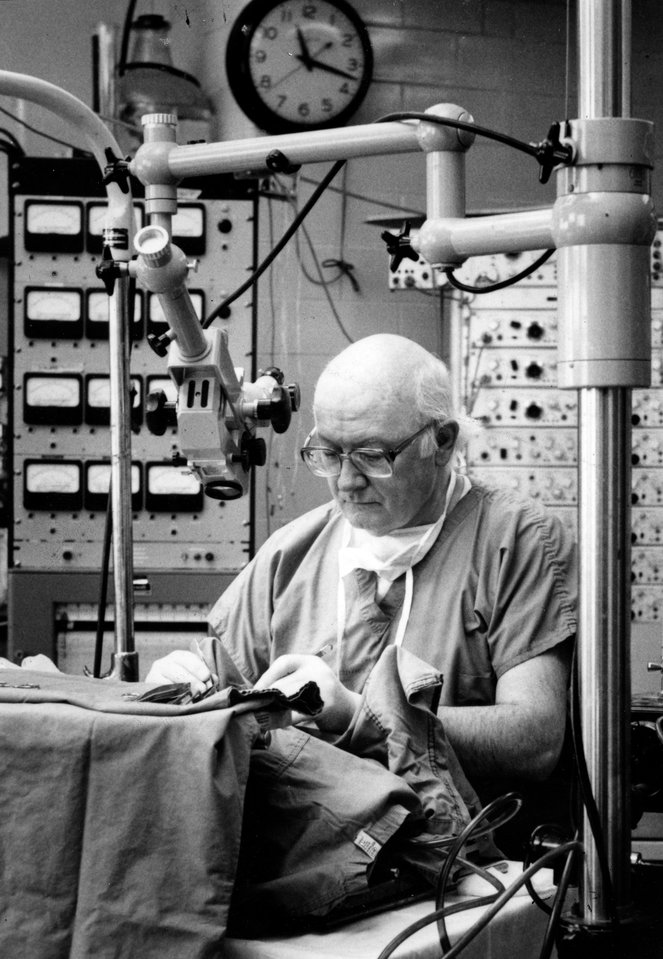

White operates on a pediatric patient.

Just as the brain has two hemispheres, White and his work evoke two disparate but nonetheless conjoined reputations. On the one hand, he was a world-famous brain surgeon with outstanding, intuitive surgical skills and whose experimental work led to the international medical community’s understanding of why the brain is protected during periods of cardiac arrest under hypothermic conditions.

The cooling blankets used on heart attack patients today? The basis for the treatment, to stave off brain damage, is in large part due to White’s research.

On the other hand ...

Though many scientists have used animals in their research – the polio vaccine, for example, is the result of 40 years of research on live monkeys, rats and mice – White gained tremendous notoriety perhaps because much of the public found one area of his research gruesome in the Frankensteinian sense: monkey head transplants.

In 1970, White, with his team in the brain research lab at Cleveland Metropolitan General Hospital (since renamed MetroHealth Medical Clinic), which he founded and led, performed the first successful mammalian brain transplant – on a rhesus monkey – surgically attaching the primate’s head onto another monkey’s body. The scientists were researching the isolation of the brain and exploring how a body given a new brain is slow to reject it.

Because of his belief that the brain is the home of the spirit, White preferred to call the procedure a total body transplant. It was his hope that one day para- and quadriplegics, whose bodies tend to fail prematurely, would have the option of extending their lives through the operation.

As for White’s monkey (the first of approximately 30 to undergo the operation), it lived eight days. After regaining consciousness it was able to smell, hear, see and even gnash at the fingers of one of White’s colleagues. It was not able, however, to move its new body, as the technology didn’t, and still doesn’t, exist to reconnect the hundreds of millions of nerves in a severed spinal cord.

This was not White’s first medical breakthrough. The research that allowed him to extend the time that a brain could survive without blood flow belonged to an experiment he conducted in the early 1960s in which he achieved total isolation of a mammalian brain while keeping it viable under deep hypothermic conditions.

In this, White pioneered the technique of lowering the body’s temperature so that the brain and central nervous system could be protected during surgery. White maintained the brain’s viability by using an “extracorporeal perfusion system.” That is to say, White and his team removed the brain of one dog, connected it to the blood vessels in the neck of another, before stitching it (encased in a fabricated sac of skin) up inside. The discovery led to the expansion of time in which surgeons have to operate on patients undergoing brain surgery, lengthening it from three to five minutes to one to two hours.

Why study a brain outside of the body? In a 1979 article for People magazine, White likened the brain in isolation to “a laboratory all its own,” that allowed him to “alter the environment, produce abnormal states like injury, cancer or stroke ... and manipulate conditions in extremely high drug dosages or with extremely low temperatures.”

In a documentary focused on White and his work, he discussed his pioneering research in developing the cooling methods that have become the standard in the treatment of brain and spinal injuries:

“We had to find some way to alter the demands of the brain,” he said. “The easiest and most scientific way of doing that is to lower the temperature of the brain. ... So I went to work working out the limits to see how cold I could get the brain, how long I could keep it cool.”

He conducted the testing on both dogs and monkeys, which, he said, were given the best anesthesia available for children. White was able for stop the deterioration of the brain and in doing so discovered that if they could lower the monkeys’ brain temperature to around 57 degrees, they could close off the brain for up to two hours.

The late Dr. Paul Bucy, a one- time professor at Northwestern University Medical School and also a world-renowned brain surgeon, told People magazine in a 1979 profile on White that White’s discoveries are “among the most outstanding contributions in the last quarter century. His work was revolutionary in the broadest sense.”

A World of Attention, Good and Bad

White himself had been known to call his work “Frankensteinian” and the stuff of science fiction. He told the Cleveland Plain Dealer in 1999, “We discovered that you can keep a brain going without any circulation. It’s dead for all practical purpose – for over an hour – then bring it back to life. If you want something that’s a little bit science fiction, that is it, man, that is it!”

He also would acknowledge that his work held some ethical concerns but ultimately determined that a number of the “wonderful advances we all enjoy in the field of transplantation, surgery and medicine are the direct result of centuries of experimental work with animals,” he said in an interview aired in another documentary, of which he was the subject.

As a result, White grew accustomed to being on the receiving end of mockery and a shortlist of nicknames not befitting an internationally respected clinical neurosurgeon and pioneering brain researcher: mad scientist, Dr. Frankenstein, even Dr. Butcher by animal rights activists who would call his home phone.

“The FBI had to wiretap our phones,” Ruth, now 45 and the youngest of 10 children, recalled. “Even though all the controversy affected us minimally, we were worried because the people who opposed his research were very aggressive.”

But if ever a scientist were designed to handle the scrutiny, it was White, who was known among his peers to enjoy publicity. In addition to writing upward of 900 scientific journal articles, he was a sought-after figure in popular culture, appearing in People, GQ, The New York Times and on the (now defunct) tabloid television program “Hard Copy,” among others. After retirement, White was contacted by Chris Carter, creator of “The X-Files,” to serve as a medical consultant for the 2008 film, “The X-Files: I Want to Believe.”

Ruth remembered her father was a contributor to local media so often he became a celebrity in the Cleveland area.

“My siblings and I would go to school and people would say, ‘I saw your dad on TV!’” she said. “He was sought by talk shows and news programs for his opinion not only in science and medicine, but also on Catholic social thought and world affairs because of his extensive travels to Russia and China,” where he visited often to train neurosurgeons.

Where Catholicism and Science Meet

What equipped White most in dealing with the controversy, and most of all shaped his approach to his patients and work, was his strong Catholic beliefs and his unshakeable calling to save lives, which for White were two branches from the same tree. His approach to research intrinsically straddled science and religion: What is the brain and how does it do what it does? Why does it think? What defines death? (To White, the answer was brain death.)

His eldest child, Bob White, 60, a recently retired Greek and Latin teacher at Shaker Heights High School, noted how his father worked to bridge the gap between doctors and religious people.

“Some religions are leery of science and doctors but he felt he would be able to explain that the science he did was not anti-God,” he said.

White and his wife, Patsy.

A lifelong, devout Catholic, White would attend Mass every day on his way home from work at Our Lady of Peace in Shaker Heights, the Cleveland suburb where he and his wife, Patsy, raised their family. He prayed prior to every surgery, and often led his patients and their families in prayer.

“He had a strong devotion to Mary,” Ruth recalled. “That’s what pulled him to church every day. That, and the fact that his work was very methodical. He was doing trauma work while raising kids, so it was important that he have that contemplative time.”

His research on cooling the brain caught the attention of Pope Paul VI, who often invited White to Rome to discuss his ideas on the moral and medical definition of death. Later, White would meet regularly at the Vatican with Pope John Paul II. He was appointed a member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences. Soon after his appointment he established the Vatican’s Commission on Biomedical Ethics in 1981 and became an adviser to Pope John Paul II on medical ethics.

His conversations with both popes, both of whom he considered friends, helped shape the Vatican’s stance on brain death and in vitro fertilization.

Some years ago over lunch in Washington, D.C., Ruth – who works as executive director of the National Center for Housing and Child Welfare – asked her father why he chose to live out his career at a county hospital in a rough neighborhood when he could have had his pick of institutions that could offer more money and more of a stage.

Her father replied with two reasons, she recalled. He wanted to conduct research. A county hospital connected to a university – such as Case Western Reserve University, where he taught and co-chaired the Department of Neurosurgery – would allow him to pursue that work. And two, working for a county hospital meant he would never have to turn someone in need away.

“He couldn’t imagine turning down emergency victims because they couldn’t afford to pay. That came from his faith,” Ruth said. He believed that “everyone has human dignity and is entitled to respect, whether you were the parking lot attendant or the pope.”

Science Fiction For the Soul

According to his eldest son, White was particularly fond of science fiction, and especially fascinated with the myth of the Modern Prometheus, both in classic forms, such as Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, as well as less critically acclaimed stepchildren of the genre, such as the pulpy 1950s film “Donovan’s Brain,” one of White's favorites, starring the future Mrs. Ronald Reagan, Nancy Davis.

Unlike Victor Frankenstein, White didn’t seek to create a creature in his experiments. White’s son Bob imagined his father’s cultural favorites were his way of seeking out “people who in effect were trying to create or – more so in my father's case – extend life, and the problems they faced.”

It seems reasonable to think that in White’s day, when he had few counterparts, he sought like-minded company in a space where imagination is eternal and vision is boundless – the world of fiction.

Recently an Italian surgeon announced his plan to perform the world’s first human head transplantation on a Russian paraplegic man in 2017, the type of procedure White had hoped to oversee before he died in 2010, and one that many in the medical community view as fantasy, at least for the foreseeable future.

White may not have lived to see the operation, but he died knowing his life-sustaining techniques have made an impact on thousands of lives.

Read more from St. Thomas magazine.