At first glance, the group gathered in O’Shaughnessy Educational Center on a rainy afternoon in mid May didn’t seem out of the ordinary from any other student group on campus. The students enjoyed a late lunch while chatting, giggling and teasing one teacher about his possible Funyun breath.

But a second glimpse would reveal that most of these students weren’t Tommies blowing off steam while finishing finals. Many of them wore neat, professional clothes with the words “Cristo Rey Jesuit High School” stitched on the front.

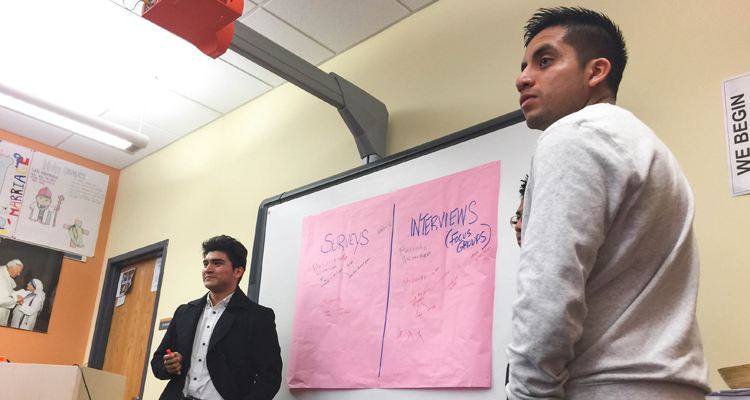

The 10 Cristo Rey Jesuit High School-Twin Cities students are members of a youth research team that came together with St. Thomas students throughout the 2015-16 academic year to explore issues related to first-generation students and college access. Backed by a $30,000 Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR) grant, they worked alongside two St. Thomas professors and four Cristo Rey faculty and staff members. The team tapped into both schools’ resources to develop a yearlong research project to improve the accessibility to – and success during – college for first-generation students.

Putting together the team

The research project sprang from an initiative to further advance Cristo Rey and St. Thomas’ relationship. Cristo Rey-Twin Cities is one in a network of 32 high schools across the country that prepare students in urban environments for college by giving them access to a quality, Catholic education. Through Cristo Rey’s Corporate Work Study Program, students also participate in a four-year internship, where they work five days a month in an entry-level position at a local organization. This position also helps them pay for their education.

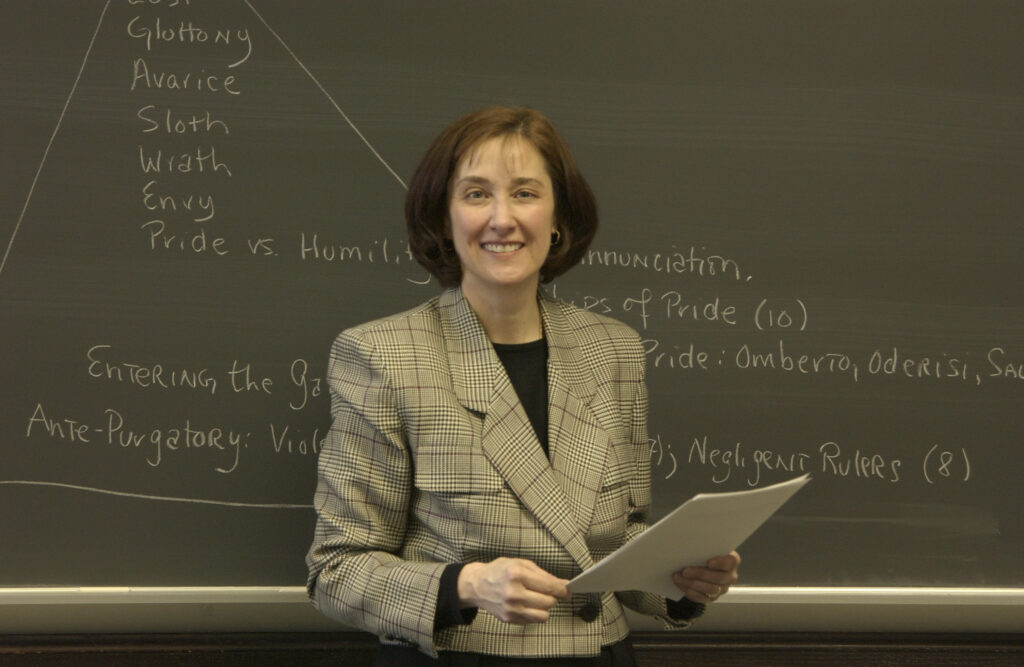

St. Thomas and Cristo Rey have collaborated with one another through various programs since Cristo Rey’s inception, but in light of the priorities in St. Thomas’ strategic plan, Carol Bruess, professor in the Communication and Journalism Department and director of the Family Studies program, began to consider how the relationship could be more profound.

“Together Possible is the idea that, separate, our two institutions are thriving, but together, so much more is possible for all of our students, especially given that our missions are so similar” Bruess said. “Part of our focus is to advance equitable access to higher education for students of color and first-generation students – the students Cristo Rey serves as the majority of their student body and a population St. Thomas wants to do a better job serving.”

With that in mind, when Bruess and Kari Zimmerman, assistant professor of history, heard about the YPAR grant, they decided to give it a try. The grant was funded by Youthprise, Minnesota Campus Compact, the McKnight Foundation and an anonymous donor. YPAR empowers youth who are typically the ones being researched by allowing them to become the researchers and leverage their own life experiences. So, to study the first-generation experience, researchers were pulled from Cristo Rey juniors and seniors, St. Thomas students who are graduates of Cristo Rey and one student who was a graduate of both.

“We’re helping students become researchers,” Zimmerman said. “I was really hoping that students felt like they had a voice in telling their own story.”

To make sure the students’ time, skills and experience were being honored, the majority of grant money went toward paying students for their work.

Bruess echoed that in addition to helping the students learn how they could be researchers, she said they wanted to make sure the students also saw how they can enact change as researchers – an aspect that appealed to many of the students. Several said they decided to get involved so they could help other first-generation students.

“I just like the fact that our project is going to help people,” said St. Thomas sophomore Jennifer Ramirez. “After all the hard work, it’s worth it because people will be helped from it.”

A first-generation reality

While the youth directed the project, the adult participants honed the students’ skills so they could make informed decisions at every step. The youth started by reading the literature about first-generation students, and then developed a research question: What type of education and preparation do parents and families of first-generation college students need to support their first-generation college student?

After deciding on their focus and receiving training on research ethics, the group split into data-collection teams. They launched online surveys to collect quantitative data and conducted in-depth interviews with parents of first-generation students; current first-generation students in college; and high school students in college-preparatory programs who will be first-generation college students. In total, the team analyzed 388 surveys and 25 in-depth interviews.

“The youth team wanted to understand the full picture and gain the broadest view – to capture the greatest number of voices on the challenges, opportunities and hurdles for first-gen students,” Bruess said.

They then began to look for themes across all their information. They broke down their observations by group and reported both findings about each group and recommendations for how the experience of that group could be improved.

While each observation and recommendation can be found in the group’s report, one of the key findings was that there is, indeed, a “first-generation reality.” Part of the reality has to do with the hidden curriculum – knowledge that one unknowingly picks up from being around family members who have been or are in college, such as how to apply, get information on financial aid and skills for transitioning well into college, such as time management.

“Across the interviews, participants talked about the assets that they have – the lived experiences, the strengths – and at the same time acknowledged a series of obstacles,” Bruess said. “One of our students said, ‘This isn’t a victim story. This isn’t “woe is us.”’ This is saying, ‘Yes, there’s a reality, and we need to recognize that.’”

One aspect that struck many members of the team was how the parents provided support. Many parents, they noted, were the emotional backbone of the family and did anything they could to provide encouragement and expressed great pride in their students.

“The unwavering dedication that these first-gen parents have toward their students succeeding in college and the desire for information is profound,” said Sarah McCann, the dean of student achievement for 12th grade and religion teacher at Cristo Rey.

Many of the parents felt as if they couldn’t provide information on the college application process, though, and financial aid was a particular source of worry.

One of the recommendations the group made was for better and increased communication with parents and first-generation students, making sure they know they aren’t alone in their struggles, and helping them network and share information and resources.

Lived experiences

Throughout the whole process, many of the student researchers said that the data and findings reflected their own lived experiences.

“The results of the surveys were often what we knew, but didn’t know how to articulate,” Cristo Rey religion teacher Nicholas Contreraz ’01 summed up.

As they paired their experiences with what their data showed them, many of the students said it made them feel better to know they weren’t alone.

“We’re all on a similar journey,” said Cristo Rey senior Ajaa Walker. “Hearing that firsthand gave me a sense that we’re all of the same mind, and it’s cool to learn that.”

Not only did the students learn they weren’t alone, but they could take this knowledge back to their families.

“I told my parents they weren’t the only ones feeling the way they do right now,” said recent Cristo Rey graduate Guadalupe Rubio Robles. “I think they’re concerned and scared to let go, but I think a lot of parents feel that way.”

“I feel like I’ll make my mom go to meetings for my little siblings and make sure they get what they need at a younger age,” said Jennifer Delgado, another recent Cristo Rey graduate. “So, when they get to my age, it won’t be as difficult. I struggled a lot through college applications.”

In turn, many of the high school students received additional information that changed their approach to how they plan to succeed in college. The current St. Thomas students imparted what they had learned after going through the college application process and as current college students, such as time management skills, studying tips, how to deal with homesickness and networking.

“One thing I told them was to make sure you join as many clubs and organizations that you’re interested in,” said St. Thomas senior Angel Paucar. “That’s a good way to make friends and build relationships, and even networking skills – it’ll give you the network you need.”

Recent Cristo Rey graduate and current St. Thomas freshman Joshua Crespo said all of that information changed how he plans to approach his time as a college student.

“Before applying to college, I was planning on just study, study, study – doing nothing else, not working,” he said. “Now, I am considering doing service projects and different activities.

Several of the professors and teachers involved said they’re also going to take what they learned back into their classrooms. Zimmerman said she is going to be more cognizant of the hidden curriculum and how she can support students, including through the content she teaches. At Cristo Rey, Contreraz said he hopes to start having intentional conversations with students about the college process earlier on.

Sharing the news

With months’ worth of data and experiences under their belt, the team compiled a 44-page report, a video for social media and a website to help share their messages. They’re hoping that, from this, opportunities will arise to collaborate more formally with high schools and universities across the country. They will present their research at a conference in October, and are making arrangements to travel to multiple Cristo Rey schools to share their findings.

The students, in particular, were excited about the video, which helped personalize their message.

“It’s awesome for us to present what we found in the research and for them to see who we are and that these students are real,” Delgado said. “We’re speaking and we go to Cristo Rey, we’re first-generation students, and we did do this data and this project.”

In the end, Bruess emphasized that this entire process was meant to be empowering, which certainly came across through the youth who participated.

“Having data proves how much we struggle through the college application process, but also how much we can improve and change the statistics that identify us,” Delgado said. “That’s a part that serves as a motivation. … [First-generation students can] see how many of us are making it, and it can change the statistic.”

For more information or to invite the youth research team to speak, contact Bruess or Zimmerman.