I teach physiological psychology, and my research focus is on sleep. Specifically, I study how and when we sleep and the environmental, biological and psychological variables that impede sleep. Simply put, I study what is it that makes us go to sleep and wake up when we do and the factors that interfere with that process.

I would say that my interest in behavioral neuroscience is both inborn and a product of my upbringing. I grew up on a farm in East Texas. My mother is a veterinarian, and our farm served as a makeshift convalescence home for injured and abandoned animals of all types (horses, pigs, gerbils, cats, dogs, llamas, emus, cows, peacocks, iguanas, turtles, chickens and geese, etc). I accompanied my mom to the vet clinic, rode "shotgun" with her on house calls, observed the necropsy process and watched how she worked to patch up, nurture and train our own brood. I remember asking my mother what specific animals were thinking, and she would answer with such precision that I believed she could literally understand secret languages of animals. She helped hone my process of observation and encouraged me to "notice what happens when… ."

My father was a health physicist and an amateur astronomer. I remember feeling in awe of the enormous range of scale he worked with – gasses measured in the parts per million in the laboratory and a telescope at home trained on objects millions of miles away. I inherited from my father an appreciation for measurement and calculation. The family games we played (Scrabble, bridge and poker) involved assessments of risk versus reward. From my father, I learned to speculate, "what would happen if… ."

Growing up, I wouldn’t have been able to tell you when football season ended and basketball season began, but I did have a sense of natural rhythms like the periodicity of hurricanes, lunar cycles, breeding seasons and blue bonnet blooms. I knew when the chickens went to roost, when the horses would start pawing and snorting for their feed and when the barn rats and cats started their nightly pas de deux. When I travelled, I noticed the different patterns in human activity; e.g., how Spaniards and Moroccans retreat for a few hours each day when the sun is overhead but stay awake long into the night, and how Icelanders reveled in the midnight sun.

When I started college at Transylvania University, a small liberal arts college in Lexington, Ky., I became acutely aware that I was a morning person living in a night owl world. I was bright-eyed for morning classes, but missed out on plenty of social events because I liked to be in bed by 10 p.m. I started off taking science and math classes but quickly became fascinated by the field of neuroscience and designed my own biopsychology major. To quote from one of my favorite hymns, I wanted to know more about "the mystic harmony/ linking sense to sound and sight."

I enrolled in a Ph.D. neuroscience program at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. My research mentors, a psychiatrist and comparative anatomist, invited me to join them on a project investigating how the rat brain responds to different types of light exposure. After speaking with Nobel Laureate Torsten Wiesel about his research on how rearing kittens in complete darkness permanently disrupted visual skills like depth perception, I was inspired to investigate what happened to animals’ sleep patterns when they were exposed to all dark or all light (like that of a neonatal ICU ward) for the first few weeks of their lives. In short, our research team found that rats deprived of light early in life were hyper responsive to light cues (like the folks who fall asleep in lecture as soon as the lights are dimmed), whereas the rats who were reared in all light weren’t able to adjust their sleep patterns to new lighting conditions (like people who are more sensitive to jetlag). These behavioral changes reflected actual anatomical differences in the eye-brain connections.

Once I began teaching college full time and I witnessed the delirium and exhaustion of students struggling to stay awake, my research focus switched from rats to students. Sleep is a good indicator of overall health, and college students in the United States are at the center of a major public health crisis. Most psychological and physiological illnesses involve disruptions in sleep, and likewise, disruptions in sleep can contribute to illness. Diagnosed mental illnesses in college students have been on the rise and freshmen are reporting higher levels of stress than any previous generation. My first research endeavor in this field was to document exactly how poorly college students are sleeping and to start to figure out what was most responsible for disturbing sleep in students.

I did an extensive survey of over 1,000 students to evaluate relationships between sleep quality, schedule, "sleep hygiene," mood, psychoactive substance use and academic performance. Not surprisingly, we found that students weren’t getting enough sleep; however, the reason for their lack of good quality sleep was surprising to me. Feeling stressed provided the largest explanatory power for poor sleep quality, whereas alcohol and caffeine consumption and consistency of sleep schedule were not significant predictors of sleep quality. These data are published in the Journal of Adolescent Health, and to the best of my knowledge, this article has the largest sample size and includes the most extensive survey on sleep behaviors of any published article on sleep in college students in the United States. This study also received considerable attention in the popular media, and was summarized as a press release by Medical News Today.

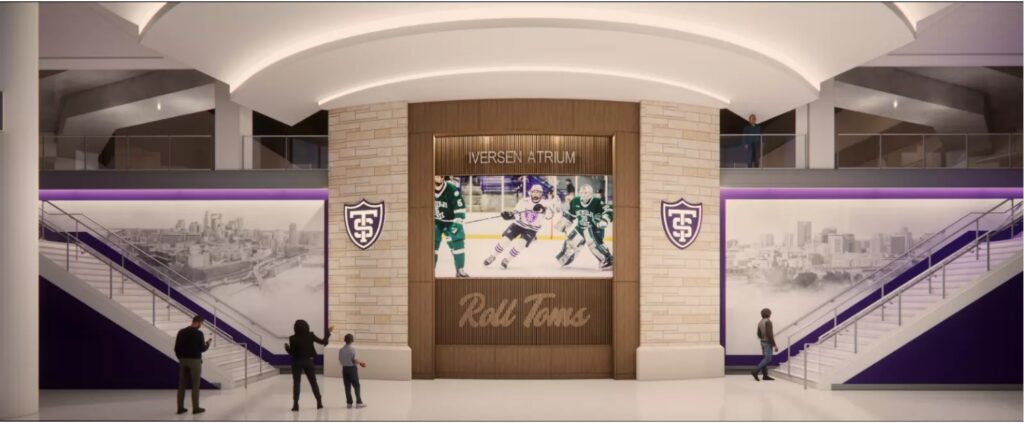

Now that we know more about how students are sleeping, our next step is to figure out how to improve it. College students in particular are notorious for bad sleep hygiene – sleeping in on the weekends, socializing, studying or playing video games late into the night, and using triple shot lattes and 5-hour energy drinks to fuel their busy lifestyles. Although most contemporary guidelines focus on improving sleep hygiene, my research suggests that teaching students cognitive and behavioral techniques to help manage their stress and anxiety might be a more effective intervention strategy. I currently am partnering with the St. Thomas Student Wellness Center to follow a group of freshmen who have gotten together every morning to enjoy a healthy breakfast and talk about issues that are stressful for students (finances, relationships, time management, etc). We haven’t analyzed the data yet, but I suspect that just taking time every day to meet and talk face to face will have a positive impact on these students’ sleep, stress and health. People love to talk about sleep, and college students are certainly no exception. Students working with me have compared levels of cortisol hormone and immune function of those students with regular schedules versus those with irregular ones; have convinced students to go to bed with their cell phones off and measure differences in their sleep quality; and have studied the effects of energy drinks on decision-making behavior. I have really enjoyed teaching students to apply a critical lens to their own sleep and health. I trained that lens on myself, too and noticed, for example, how my sleep switched to a bi-phasic pattern during the last few weeks of pregnancy to a fragmented delirium during the first week with our newborn daughter. My hope is to figure out ways to make everyone sleep a little better in this frenetic, caffeinated 24-hour world.

Roxanne Prichard is professor of psychology at the College of Arts and Sciences.

From Exemplars, a publication of the Grants and Research Office.