At 6:05 p.m. on Aug. 1, 2007, the architectural landscape along Minneapolis' scenic riverfront dramatically changed. A gusset plate holding together the I-35W bridge failed, sending the structure plummeting into the Mississippi River. One-hundred-eleven vehicles were impacted and 13 people ultimately died.

The process of recovery began almost immediately, involving 75 local, state and federal agencies, among them the Washington County Sheriff's Office. Mike Barrett, associate director of the St. Thomas Public Safety Office, and Wayne Johnson, Public Safety's Minneapolis campus manager, served on the office's water recovery team.

Barrett, a deputy sheriff and 16-year volunteer with the office, served as a dive tender in the recovery operation. Johnson, a retired deputy sergeant who continues to volunteer, was a diver.

With the anniversary approaching, they recently returned to the 35W bridge and reflected on their experience.

What was your role on the recovery team that day?

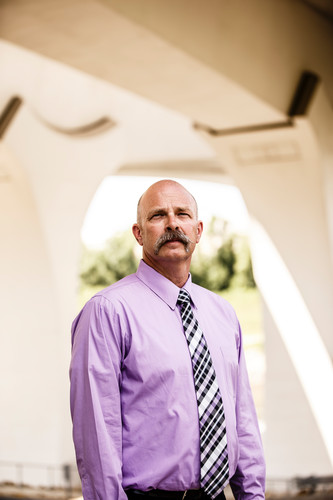

Mike Barrett

MB: We provided mutual aid assistance to the Minneapolis Police Department, the Hennepin County Sheriff’s Office and other federal agencies on a recover operation. Our primary duties were to identify underwater targets and to map and clear them. Vehicles found were searched and cleared to ensure there were no bodies inside. My specific assignment was land support as a tender.

Tenders direct divers with voice commands using a communication system built into the ropes used to secure them.

WJ: My role during the recovery was as a diver to locate and identify vehicles and any other subsurface hazards, identify underwater evidence and recover human remains. At one point during the dive operations we had located a government vehicle that needed to be thoroughly searched and have any computers or documents recovered.

What was most memorable about the day?

MB: It was a very long 18-hour day. It felt surreal to be in the city limits of Minneapolis and hear only the sounds of nature and no city noise or vehicle traffic.

WJ: It was a very solemn work environment, as it always is on these types of tragedies. I remember also being surprised and shocked that in this day and age a bridge of this magnitude could just fall into the river. And of course we had our concerns about what really happened, as we were just a few years removed from the 9/11 attack.

I had been in Desert Storm and remember what it was like to see blown up buildings. And here we were seeing something like this but in the middle of Minnesota.

With so much debris in the river, the conditions must have been treacherous.

WJ: If you look at any of the photos of the bridge collapse you can see the amount of concrete, vehicles leaking gas and oil, rebar that was sticking out at all sorts of weird angles. The fear of the bridge continuing to collapse upon itself, plus the speed of the river due to the recent heavy rains, created a very treacherous environment for diving.

Most people can’t imagine what diving in dark water is like. It's like standing in your closet at midnight with your face in a bowl of chocolate pudding. There's no light so you must do everything by feel. Each object you touch you have to try to use your mind's eye to figure out what it is and decide whether it's an object of interest or just subsurface clutter.

MB: Our advanced training and preparation was no match for how dangerous it was. Over the course of the operation, we had several divers lose communication with tenders due to stressed communication lines. Some divers were literally sucked under the collapsed bridge due to fast moving water.

That day I tended a diver from a neighboring agency who was one that was sucked under the debris. I lost communication with him and he was unable to understand my rope signals because he wasn’t trained with our methodology. This led to a policy change about who dives with our team and what credentials they need to have.

It must take an incredible amount of bravery to enter the water under those conditions. Were you scared?

Wayne Johnson

WJ: As I look over what I have done in my life, 32 years of military and civilian law enforcement, veteran of the Persian Gulf War and 24 years with the Washington County Sheriff's Office, the diving under the 35W bridge was my closest near-death experience.

As I was under searching a vehicle for remains or evidence my line had somehow become slack. With no visual reference I was unable to determine where I was on the bottom of the river. When my time was up for me to surface, which is limited by my air supply, I began my ascent believing I had a clear assent to the surface of the river. However, with the heavy current I began swimming up only to find I was trapped under the bridge; I realized that with the amount of rebar and other subsurface clutter it would have been extremely difficult for my lines not to get entangled and me to get out of there without running out of air and drowning.

I just remember thinking very clearly that this was going to be the end, but by the grace of God the surface support team managed to pull me out and I was able to get free from up under the bridge deck.

How did this compare with other recovery operations you have experienced?

WJ: This operation was different because of the the sheer scale. We've done other operations with another team or two but never this many teams or agencies involved from local, state and federal levels.

MB: Hearing stress in the voices of very experienced team members, losing the ability to communicate and calm them, the event being in the national news cycle for so long, and a site visit from First Lady Laura Bush certainly made it unique. The sound of Marine One sure broke up the monotony and serenity of the day.

It must be mentally and emotionally taxing to do this type of work. How do you deal with that?

MB: More than anything knowing we are providing a unique service few people choose to do: help families and survivors in their healing process.

WJ: It is very taxing. It's difficult emotionally because you are looking for someone's loved one. During an operation you compartmentalize those emotions and feelings because you realize you have a job to do. But then after the job is over that's where sometimes professional help is sought for dealing with some of the issues that are encountered. We are a very close team and we talk and work through it.

Are you still in touch with people who assisted on the recovery?

MB: Many of us have remained on the Washington County water recovery team, or keep in touch with past members. The connection with those partners is and always will be about assisting families with closure.

WJ: The dive community in this area is very small and specialized. This type of work is a calling. It is a very important mission and we all understand that and it’s not for everybody. Many of the people on the Washington County Sheriff's Office water recovery team are still on the team today because of that sense of pride and duty.

What motivates you to do this type of work?

MB: The teamwork involved, knowing how critical the work is for our community, that few people actually choose to do it. And closure – that we can help find and return loved ones to grieving family members.

WJ: At the sheriff's office there are not a lot of people volunteering to be part of the water recovery team. It is very important work and I have a skill that can be utilized to bring closure for someone’s family. But with that being said it is not just about my skill alone; for every one diver that's in the water it takes four people on the surface for that diver to be successful and safe, so it's very much a team feeling. It's not an individual endeavor at all.

--

In 2008, Barrett was awarded the St. Thomas Distinguished Citizen Award in part for his work on the 35W bridge recovery efforts.