Pirates. Those fearsome, fearless swashbucklers from days of yore earned a reputation for taming the dark. In this light, they might help us understand better why we feel anxiety, according to a St. Thomas study by recent graduates Megan Coffman and Grace Vo, and Dr. Sarah Hankerson of St. Thomas' Psychology Department. Their project, "Correlates of Anxiety in a Dark-Induced Environment," examines why are we afraid of the dark through the lens of neuroscience.

The project drew its inspiration from a 2007 episode of MythBusters, which tested a theory that pirates wore eye patches in daylight to help them see in the dark.

"This is a test to see if fear of the dark stems from an inability to see or if it's something else," Hankerson said. "Those who wear the eye patch should have better vision. That's supposedly why pirates wore a patch, so one eye could see in the dark."

Vo '13, a medical scribe in the Emergency Department of St. John’s Hospital and Hennepin County Medical Center, and Coffman, who graduated in May and now studies speech-language pathology at St. Cloud State University, presented a poster of the project at the Midwest Psychological Association Conference, held last May in Chicago. They plan to submit their findings to a scientific journal.

Six St. Thomas undergraduates – Alex Beaulier, Nina Elder, Jon Gall, Ben Gervais, Taylor Jorgenson-Rathke and Avi Manda – assisted Coffman and Vo, who served as co-leads on the project. "Most people don't realize how much literature research you need to back up experiments before you're ready to write," Elder said.

Coffman and Vo enlisted 70 St. Thomas undergraduates to solve a Fisher-Price puzzle – designed for toddlers – in a small, sterile and (some might find) eerie room in the basement of the John R. Roach Center. Vo jokingly called it "the rat-training room." Half of their test subjects wore an eye patch for 20 minutes before venturing into the completely darkened room. The other group did not.

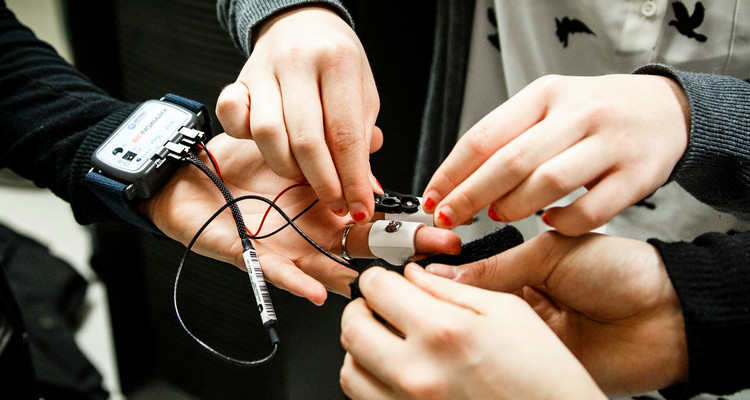

Before entering the room, they plastered each student with a jumble of electrodes, which the team used to measure physiological responses, including heart rate, pulse and electrodermal activity (perspiration), as well as respiration via a chest strap not unlike a Polar heart-rate monitor used by runners. They monitored all activity just outside the room in real-time via a laptop loaded with specialized software. Each participant sucked on a cotton swab before and after solving the puzzle; Coffman and Vo later tested the saliva samples for changes in levels of cortisol, a hormone released in response to stress, and testosterone, a hormone they linked to sense of control.

Students entered the darkened room blindfolded. After removing the covering, they were tasked with first locating the table containing the puzzle; solving the puzzle, which had them sliding six different shapes into their corresponding slots; then finding their way back to the door. Not surprisingly, the "pirates," or the students with one dark-adjusted eye, completed the test overwhelming faster than those who did not wear the patch, as they were able to see the room as if it were dimly lit though the room was sealed from light.

After completing the puzzle, both groups rated their anxiety during the experiment in a series of questions based on the Zung Anxiety Scale, one of a few standard surveys used by psychologists to measure anxiety.

The results? The less visible, more intangible of their measurements – the hormones cortisol and testosterone – provided the most illumination. The "pirate" students experienced marked declines in cortisol from pre- to post-puzzle, meaning they felt less anxiety immediately after completing the puzzle versus while they waited – bedecked with eye patch – to begin. The results of the testosterone samples weren't as striking, but "there was a trend," Vo noted: "Testosterone levels didn't show significance between conditions, but they appeared to increase more in those who wore the eye patch, showing that dark adaptation may increase the body's hormonal measure of control."

Although the heart and respiration rates of the non-eye-patch-wearing bunch didn't rise as they predicted, both groups experienced increased sweating while in the dark, a result they didn't expect. Though scientific results can only take researchers so far into the human mind, Coffman surmised that this sole indication of the eye-patched group's rise in anxiety during the study was "possibly attributed to the dark room. Even though they were 'prepared,' there is still an innate fear of the dark.

She added, "Dr. Hankerson always talks about how, evolution-wise, things relate. In prehistoric times, humans lived under the threat of night-time attacks by predators. Darkness delivered all these scary variables to early humans, and maybe that's why we're afraid of the dark. It's a hypothesis, but it could explain why our heightened anxiety with the dark remains with us today.

Alas, whether our fear of the dark is more frightening than walking the plank, remains to be seen.