Death and taxes – two sure things in life. Elder law covers both. And a growing need for experienced elder law attorneys to serve an aging population has compelled St. Thomas Law students to specialize in this area. As a licensed mortician, I realized there was a need for end-of-life and death planning. My knowledge of government benefits only scratched the surface, so applying to the University of St. Thomas School of Law, with its dedication to both social justice and elder law, made sense.

I was an advanced student in the Elder Law Practice Group (ELPG) clinic for two years at the St. Thomas Interprofessional Center for Counseling and Legal Services and served as a summer law clerk paid through a Public Interest Law Fellowship grant. My clinic experience was critical in paving the way to my thriving elder law practice, including my involvement on the Governing Council of the MSBA Elder Law Section. I absolutely love what I do.

Many other practicing elder law attorneys credit the ELPG for providing the training and experience needed to thrive in this practice area, such as Laura Orr ‘10 J.D., who was an advanced ELPG clinic student for two years. She said her experience taught her valuable interviewing and counseling skills and opened doors for meeting members of the elder law community.

Many began their law school search unware of elder law, including Orr. Only after exposure to the elder clinic did she become intrigued by the practice. The clinic’s pedagogical approach exposes students to the basics of elder law to provide thorough and confident representation.

After graduation, Orr supervised students as the elder clinic law fellow for three years. Now, she is the chair of the Governing Council of the MSBA Elder Law Section, and she has a high volume

elder law practice as an attorney at Southern Minnesota Regional Legal Services. Five years with ELPG instilled in Orr that “Courage is a necessary component of being an effective advocate. Recognizing the need for courage to march forward with a particular action – whether it was my first time or the first time for anyone – was a formative experience,” she said.

Elder Law is Expanding

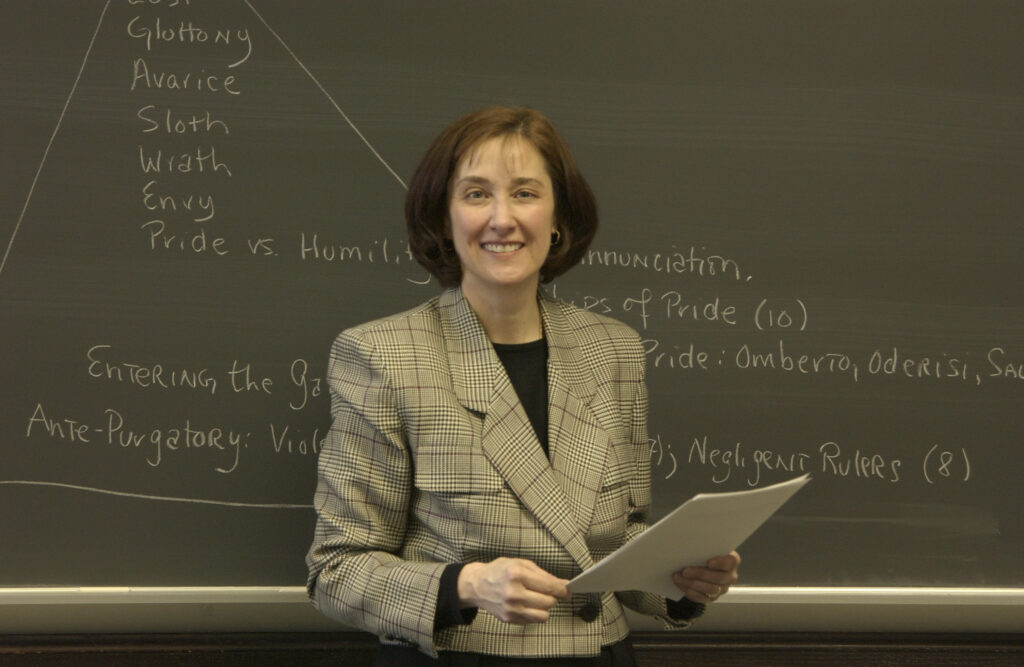

“We should determine what aging looks like,” said Jennifer Wright, newly retired clinical director of the elder clinic and professor. She is a champion in the field of elder law and has received accolades such as the 2016 Mary Alice Gooderl Award winner and 2017 St. Thomas School of Law Dean’s Award.

The demographics of legal clientele have shifted because Baby Boomers are aging. In reports issued by the U.S. Census Bureau, the number of Americans aged 65 and older is projected to be 83.7 million in 2050, almost double its estimated population of 43.1 million in 2012. That makes elder law a thriving practice area. An aging population will create sweeping changes to consumer marketing, federal health spending and law practices. Consequently, all attorneys, even those who are not elder law practitioners, must learn the nuances of advising an older population.

Elder law is the legal practice of long-term care planning for persons over the age of 18 who are mentally or physically infirm. What separates elder law attorneys

from estate planning or probate attorneys is the merging of these areas with government benefits. An elder law attorney may assist a client with real estate transfers, gift tax issues, benefits, or litigation arising from family conflict or capacity issues. Medical Assistance (Medicaid) laws are complex and ever-changing, so exposure to the basics is critical before practicing

in the area.

Apprenticeships and Experiential Learning

Law schools have attempted to marry theoretical and practical experiences for students for decades; namely, since the ABA published the MacCrate Report providing recommendations

for improving legal education. However, with law school admission numbers declining, and law schools cutting programs, fewer clinic opportunities exist. Law schools should be expanding, rather than eliminating, clinic opportunities. The supply of elder law attorneys entering practice is decreasing while the need is increasing exponentially.

The roots of the American legal profession lie in apprenticeships. During the colonial period, an apprenticeship or clerkship was essential for being admitted to the bar. Some states are reducing the theoretical classroom requirement for bar admission and favoring experiential learning. States such as California, Vermont, Virginia and Washington allow apprenticeship to count toward bar admission; Maine and New York allow a combination of classroom time and apprenticeship; and West Virginia allows students from a non-ABA-accredited law school to take its bar exam by doing three years of apprenticeship.

Wright’s commitment to clinical legal education, and her zealous advocacy for vulnerable adults, fostered a passion for elder law in ELPG graduates. She believes St. Thomas graduates are extraordinary elder law practitioners because their ELPG experience included faith and an emphasis on the common good, not just the bottom line. A significant number of active attorneys in the MSBA Elder Law Section are St. Thomas graduates.

The Future of ELPG: Center for Excellence in Supported Decision Making

With Wright’s retirement comes a shift in the focus of the elder clinic. John Kantke ’07 J.D. is head of the Elder Law and Guardianship Alternatives clinic, made possible by the Center for Excellence in Supported Decision Making, a partnership of several Minnesota not-for-profit and government agencies. The center received a federal grant from the Administration for Community Living.

Kantke was an elder clinic student for three semesters. He is the former chair of the Governing Council of the MSBA Elder Law Section and is a full-time practicing elder law attorney at Estate and Elder Law Services. He also regularly teaches Ethics and Aging for the master’s program in gerontology at Bethel University. Minnesota enacted legislation creating criminal and civil penalties for perpetrators of vulnerable adult abuse, specifically financial exploitation, with help from groups such as the Minnesota Elder Justice Center.

Even with the state legislative changes, there is much to be done to educate attorneys. Many elder abuse victims are left without representation because there are little resources to handle these, which are time consuming, and the victims are typically indigent or receiving government benefits, thus unable to pay attorney fees. The elder law bar is working to provide pro bono opportunities for attorneys, and looking to pair with the civil litigation section of the MSBA, as well as other pro bono groups, to provide these necessary services to vulnerable adults.

By dedicating resources to other growing areas within elder law, such as training mediators who specialize in government benefits and are knowledgeable about the unique circumstances vulnerable adults encounter, or by providing assistance to abused elders (financial exploitation), St. Thomas will continue to be a leader in elder law education.