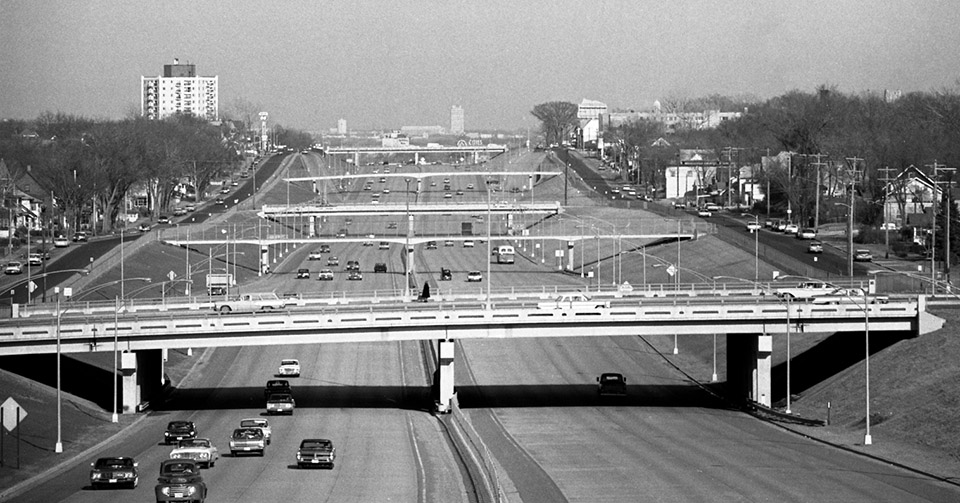

Tens of thousands of people drive on Highway 94 and Interstate 35 coming into and going out of St. Paul every day. Not many think of the pavement itself as a legacy of community struggle against their government. Those struggles are exactly what history major Whitney Oachs, a junior, dug into with a summer’s Young Scholars grant: She researched the citizen organization and protest that fought back against government plans to build highways through their communities.

In the 1960s, those plans were realized by the construction of 94 through the heart of the predominantly African-American neighborhood of Rondo Avenue, which displaced some 600 families. The following decade, plans to construct I-35 through south St. Paul were met with community resistance as well; such opposition over many years resulted in the “practice highway” with a 45-mile-per-hour speed limit that stands today.

“I felt like it was necessary to take a look at the Twin Cities’ history of protest politics, which led me to Rondo and 94, and the national phenomena of highway construction and urban renewal that decimated tons of primarily black, working-class communities across America,” Oachs said. “To fit the Twin Cities into this national context of highway construction was really important and something not a lot of people have delved into on a large scale.”

Oachs dedicated the majority of the summer’s beginning to reading about everything that happened.

“What really strikes me about the narrative surrounding highway construction was the grassroots social organizing that took place when they found out about these policies and plans,” she said. “There was an amazing organization put together by the Rondo community to combat it. They didn’t succeed, but they were organized and poised. The same thing with [the community organization group Residents In Protest of] 35-E; even though that was a middle-class, white organization, they drew on those [Rondo experiences] to rise up and say, ‘It’s not OK what you’re doing.’”

Oachs said the initial research “was pretty defeating” because of the way everything ended. But meeting with Marvin Anderson, one of the co-founders of Rondo Avenue Inc. gave her a different perspective of hope. Rondo Avenue Inc. leads the preservation efforts of the community’s history and, among other things, has organized Rondo Days for more than three decades.

“There is nothing like that in the entire nation for people who had been displaced by highways,” Oachs said. “It showed me the reason we remember Rondo in a different light is that they took historical memory into their own hands, gave themselves agency and demanded the city and state to see them for what they wanted to be seen as. That’s a really important part of this.”

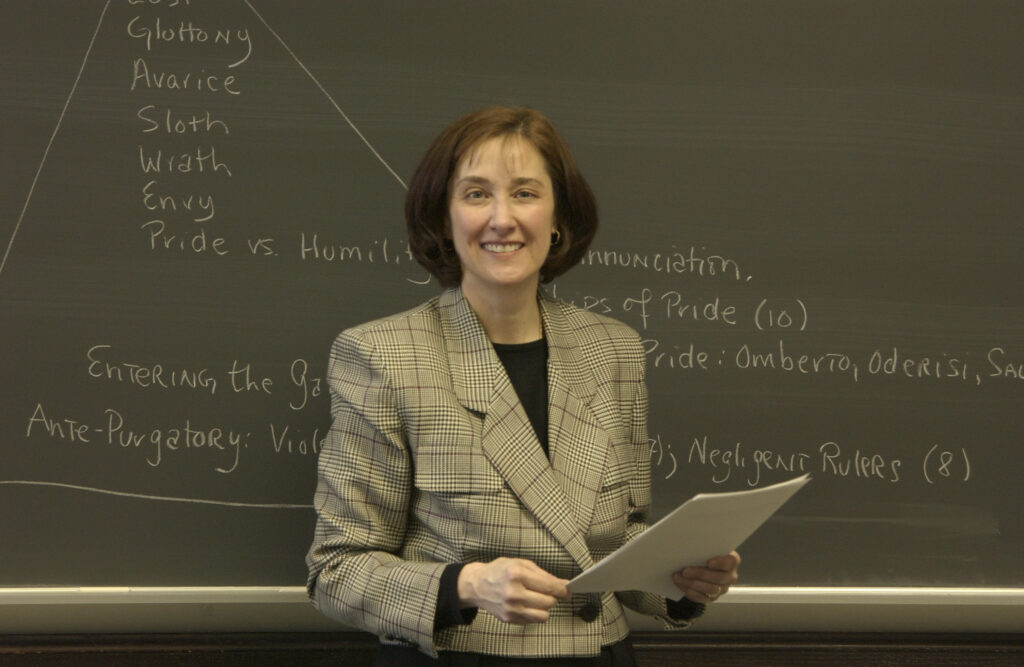

Oachs’ adviser, David Williard, an assistant professor in the History Department, said he was impressed by her approach to research, which helped get a view “about how choices of where space and money and communities intersect change what a city looks like, where people live,” he said. “To show that’s about choice, politics, policy, and responding to that and trying to maintain a sense of self and community identity within that. That’s the real energy behind what she’s doing.”

While Williard also cautioned for historians not to try to make history connect to the present too directly, he said Oachs had the right approach to see how the roots of past issues apply today.

“These highways continue to perpetuate inequality. 94, north of the highway on University, has continued to become more diverse, more of an immigrant community. The south side of the highway, like on Selby Avenue, has continued to be more gentrified and more white,” Oachs said. “These highways, particularly in St. Paul, created islands that separated neighborhoods from other neighborhoods. You could spend all your time in one neighborhood and then go where you wanted on the highway and never have to interact with these other diverse communities because of the way our highways are set up.”

The ability to draw those connections to the contemporary world is a huge component of why Oachs enjoys history, she said, and why she plans to continue working on this project next summer and into the future.

“I don’t see what I’ve done as being finished in any way,” she said.