Teachers, students, writers and lovers of children’s literature gathered with authors David Weisner and Carrie Mesrobian on Saturday, Feb. 21 for the twenty-third annual Hubbs Children’s Literature Conference. This year’s conference explored wordless picture books and “edgy” young adult novels.

“Everything we do here is so relevant,” said Bob Nistler, associate professor and chair of the Hubbs conference planning committee.

Nistler teaches communication and children’s literature in College of Education, Leadership and Counseling teacher licensure programs. He has used Weisner’s work with his students.

“It’s very easy to work this stuff into the classroom because it’s all award-winning material and you can use it in the elementary classroom,” he added.

David Weisner constructs stories through wordless picture books

It would be hard to find a children’s author more award-winning than Weisner. He is the second person ever to be awarded the Caldecott Medal three times – for Tuesday in 1992, The Three Pigs in 2002 and Flotsam in 2006. Three of his other books – Sector 7, FreeFall and Mr. Wuffles! – were named Caldecott Honor Books. David was also the United States nominee and a finalist for the 2008 Hans Christian Andersen Award.

At the conference, authors offer their deep and unique insights as artists and writers. Senior Sophia Bensen, an elementary education and American Sign Language major with a minor in music, attended the conference for the first time. She also volunteered and had the assignment of acting as a guide for Weisner, and giving his formal introduction before his presentation. She joined Weisner, Mesrobian and education faculty for an informal dinner on Friday night. It enhanced her experience of the conference.

“Going out to dinner allowed us to get to know David better as a person, which is so cool. I got to go out to dinner with a three-time Caldecott Medal and three-time Caldecott Honor Award winner! What!?” Bensen reflected after the conference. “We were also able to talk more in depth about topics that I was particularly interested in, like activities that I could use in my future classroom. David [Weisner] shared a bunch of ideas that teachers have used in their classrooms. It was also great to talk more to Carrie [Mesrobian]. She used to be a teacher and is very real. She talked about her personal experiences and gave us advice on student teaching.”

In their presentations, both authors touched on aspects of children’s literature relevant to classroom teachers. In Weisner’s experience, his explanation of his creative process helps educators understand the oxymoronic genre of the wordless picture book.

“From the first time I spoke at a conference, people would tell me ‘I had no idea how to read the book.” Weisner said.

For Weisner, there is no right way to “read” the pictures, it is simply a matter of paying attention to the details in the illustrations. In his talk, Weisner explained that what a writer creates with words, he constructs with pictures – a fanciful world believable through its own inner logic. Every detail of the picture fits together so that the story can be “inferred” through the image. Weisner also shared how children have responded to his books.

“They usually want to tell the story,” he said.

He has seen children retell his stories in movies, books, pictures and plays.

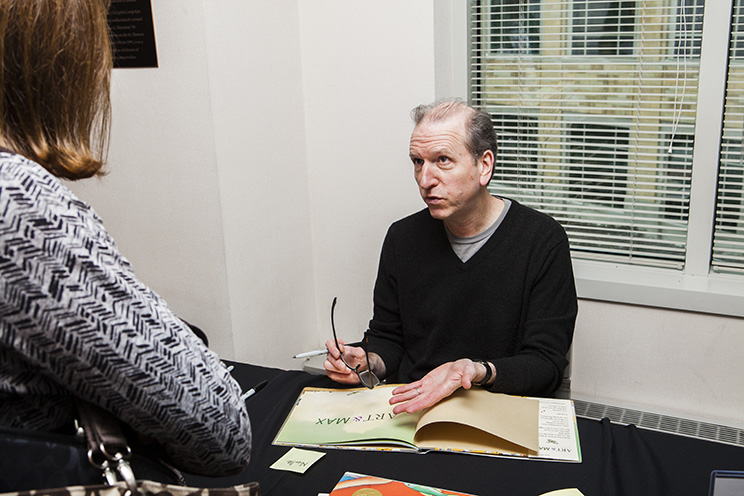

Local author Carrie Mesrobian signs books at the 23rd annual Hubbs Children's Literature Conference.

Mesrobian pushes boundaries with Sex and Violence

Minnesota author Carries Mesrobian shifted the conference from the world of children’s fantasy to the sometimes all-too-real world of adolescence. In her talk, “Welcome to the Edge, YA Readers and YA Fiction,” Mesrobian addressed the question of appropriateness in young adult fiction. According to Mesrobian, “literature has shifted from a genre of neat, tidy stories to realistic depictions of the young adult experience.” Social media debates with hashtags – phrases preceded by a # sign, used to identify messages on a specific topic on social media, such as #YAkills and #YAsaves – underscore the divisive nature of the debate over YA literature.

The author’s latest novel, Sex and Violence, tells the story of a white, 16-year-old-boy’s recovery from an incident of sexual violence in which he was the victim. According to Mesrobian, “edgy” is just one of the descriptions reviewers have given the book – despite the fact that it contains only two sex scenes and one scene of violence, all brief and none graphic. Mesrobian questioned the glib classification of her work as an imposition of social stereotypes.

“It means there is sex, drugs and rape,” Mesrobian said of the term. “If it happens to characters of color it’s ‘urban,’ but if it happens to white, middle class suburban kids, it’s ‘edgy’.”

Mesrobian redefined edgy – taking the word away from these assumptions and into a reader’s personal limit.

“There is clearly an edge for some people,” she said.

What seems to breach the limit of reality or propriety depends on a person’s race, where he or she lives and his/her sexual orientation. The edge of each person’s experience is different and an edgy novel can be a challenge for the reader to enter into the reality of another. “Is there a limit to our empathy, our curiosity, our ability to imagine the world?” Mesrobian asked.

As a former high school teacher, she is also aware that literature can adversely affect young people. She described students she knew who admitted the depictions of romance in the Twilight series had badly influenced their own relationships.

With all of this in mind, Mesrobian seems to always be stretching the edge of her personal limit as a writer while tapping into her younger self to approach her stories from the perspective of young readers.

“I don't think about what young adolescents need to know,” she said. “I think that's too big of a data set to consider. Instead, I try to remember what the landscape of my own brain looked like when I was a teenager, and write to the concerns and questions I had.”

Mesrobian’s insights resonated with Bensen.

“Her talk got me thinking about the type of novels that I do and do not want to use in my classroom,” the education student said.

The Hubbs Children’s Literature Conference will return to CELC next year – the 24th annual conference will take place on Saturday, February 20 in Thornton Auditorium on the university’s Minneapolis campus.