This entry was curated by Dr. Eric Kjellgren, director of the American Museum of Asmat Art (AMAA), and Dr. Shelly Nordtorp-Madson, chief curator. They are both on the clinical faculty of the Art History Department.

Determining the Top 10 Works of Art at St. Thomas was a difficult task. The collections are diverse, ranging from religious images, to centuries’ worth of western secular art, to African objects and the unique Asmat collection, so a variety of methods were employed in order to choose those pieces that appear in the list. The works must be on display, and should be located where students can interact with them. They should represent a variety of materials and techniques. The significance of the objects to their cultures is a crucial factor, as well as connections to the university.

10. Detail of fresco, “The Seven Virtues: Hope”

10. Detail of fresco, “The Seven Virtues: Hope”

Artist: Mark Balma

Materials: Fresco technique, pigment bonded to plaster

Location: Terrence Murphy Hall ceiling, Minneapolis Campus

Hope is played out against a deep blue sky, dark before the rays of sun bring the promise of a new day. The figures represent the cycle of life. A woman holds up her newborn child, who represents a new generation in whom we place our dreams. The young man in the prime of his life is bent over, laboring in the soil. Near him is a flourishing fruit tree in full bloom. His hope is knowing that he will reap what he sows. On another level, we must remember that our hope lies in respecting and caring for the earth. The elderly woman completes the cycle, but she is not a static member of this scheme. She represents the universal grandmother who has laid the groundwork for us to sow our dreams. She carries compost in her wheelbarrow, showing that what dies does not end, but becomes the basic elements needed for new life. In the same light, the pinnacle of symbolic hope in the Christian tradition is the lamb. Amid darkness is the sun, or the Son of the world, who sacrifices himself as the pure lamb in order that we may have the essence of hope

9. Garment Register

9. Garment Register

Artist: Harriet Bart

Materials: Mixed media in book form

Location: Donated in honor of the Luann Dummer Center for Women, first floor of the O'Shaughnessy Educational Center, St. Paul campus

This mixed media work, in the form of a ledger, incorporates fabric insets and poetry. It is signed, Copy D (edition included 25 copies and five artist proofs), and rests on a book stand.

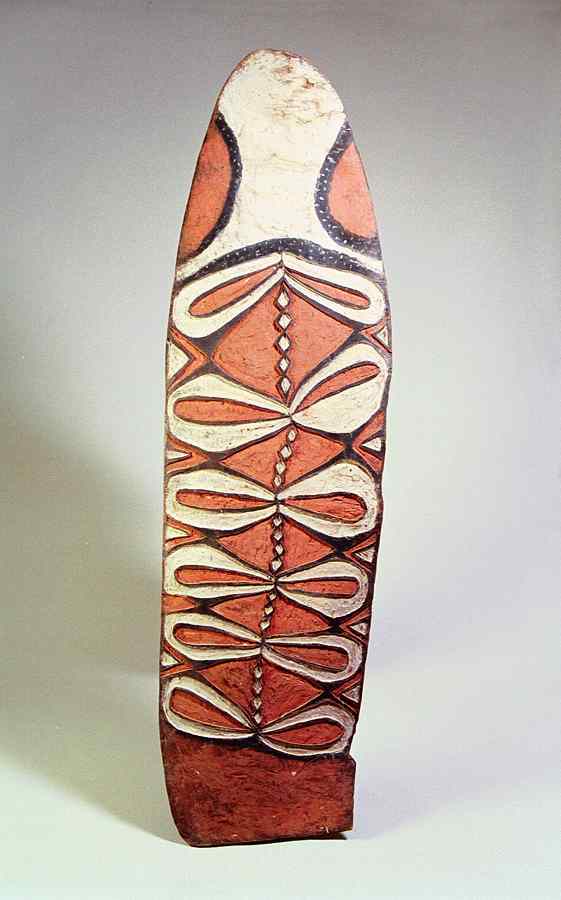

8. Shield

8. Shield

Artist: Djisriwit, before 1980, Asmat people, Yupmacain region, Vakam village

Materials: Wood, paint

Gift of the Diocese of Agats

Shields were one of the most widespread and significant Asmat art forms and this boldly patterned shield is an exceptional expression of the form. Formerly used for defense in war, shields also have visual language all their own. On this work, created by the artist Djisriwit, the top of the shield represents the head of an ancestor, his face shown in white and his cheeks in red. Below it is a central row of small diamond-shaped motifs representing navels, flanked by the oval designs that depict stylized fish and leaves, combining human, animal and plant imagery into a single powerful composition.

7. Stained Glass, King Arthur

7. Stained Glass, King Arthur

Artist: Conrad Pickel Company

Materials: Stained glass panel in larger window

Location: O’Shaughnessy-Frey Library, O’Shaughnessy Room, St. Paul campus

The Conrad Pickel collection of more than 100 stained glass panels was part of the decorative program for the O’Shaughnessy-Frey Library. Broken down thematically by location, King Arthur is one of the panels of literary heroes in the O’Shaughnessy Room. The Conrad Pickel company is still in existence and produced the most recent window, dedicated to Zora Neal Hurston.

6. Ancestor Mask

6. Ancestor Mask

Artist: Unknown, 1980, Asmat people, Joerat region, Yaun Yufri village

Materials: Fiber, wood, feathers, paint

Gift of Bishop Alphonse Sowada, osc

This Asmat ancestor mask is a powerful and expressive example of an art form central to Asmat ritual life. Virtually all Asmat communities celebrate the mask ceremony, a sequence of rituals that culminates in a dramatic rite in which the spirits of the dead, portrayed by dancers dressed in full-length body masks, revisit their home village before journeying onward to safan – the land of the ancestors. In the past, the decision to wear an ancestor mask was not taken lightly as the man who agreed to wear it was expected to take on all the duties of the deceased, including raising his or her orphaned children.

5. Initiation Mask from the Sande Society

5. Initiation Mask from the Sande Society

Artist: Mende, Sierra Leone

Materials: Wood

Location: O’Shaughnessy Educational Center lobby gallery, St. Paul campus

Acquired through the generous assistance of Dolly Fiterman and a gift from Grady and Barbara Webster

The Sande Society is responsible for the education and initiation of young girls. Secluded in a camp outside of the village, initiates receive instruction from female elders in a range of subjects including: village histories, economics, codes of conduct, child rearing and dancing. After a period of several months, the initiates emerge from the Sande camp as socialized adult women ready for marriage. While women rarely wear or perform with masks in Africa, the Sande Society is an exception. Masked female dancers appear within the camp, providing models of proper behavior for the initiates to emulate. The delicate features and elaborate hairstyles of Sande masks embody ideals of feminine beauty. The rings around the neck possibly represent the form of a chrysalis, an appropriate symbol of the transforming powers of initiation, or the ripples in the watery realm where Sande spirits reside.

4. Soul Canoe (Wuramon)

4. Soul Canoe (Wuramon)

Artist: Amandos Amonos and assistants, 1976, Asmat people, Joerat Region, Yamas village

Materials: Wood, paint, cassowary feathers, cassowary quills, seeds, fiber

Gift of the Diocese of Agats

This dramatic soul canoe is one of the most historically important and best-known works in the AMAA. Carved in the form of long canoes crewed by spirits, soul canoes (wuramon) are the largest of all Asmat sculptures and were predominantly created for use in a ceremony in which adolescent boys were initiated into adulthood. This soul canoe was one of a group commissioned in 1976, which helped spawn the cultural revival both of this important art form and the initiation ceremony.

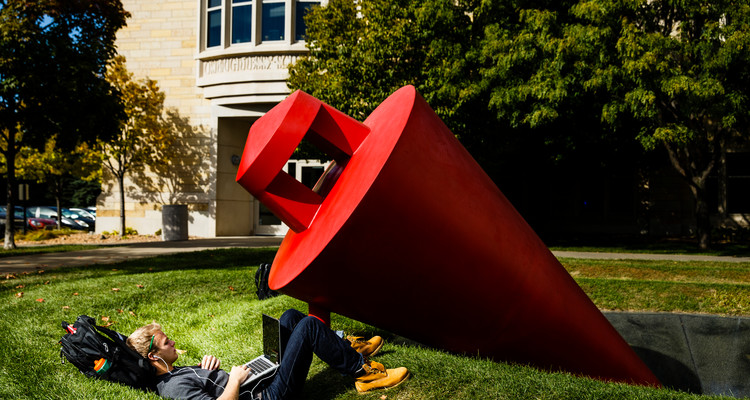

3. "Plunge"

3. "Plunge"

Artist: Janet Lofquist

Materials: Steel and granite

Location: Part of Science Halls art project, St. Paul south campus

Informally known around campus as the “plumb bob,” "Plunge" indeed replicates this basic tool on a colossal scale. Created of steel, painted with red enamel and with a 3-foot-long steel tip, it appears to be rotating in a recessed and sectioned conical form made of 12 triangular pieces of granite. Three slightly elevated sod rings encircle the granite cone.

2. Bis Pole

2. Bis Pole

Artist: Unknown, before 2003, Asmat people, Bismam region, Buepis village

Materials: Wood, paint

Gift of Fred and Kato Guggenheim in honor of their son, Scott Guggenheim

This work is an outstanding example of one of the most-renowned Asmat art forms: towering ancestor poles, called bis in the Asmat language. The poles form centerpieces of memorial feasts, which commemorate people who have recently died and assist in sending their spirits to safan – the land of the ancestors.

1. Archbishop John Ireland

1. Archbishop John Ireland

Artist: Michael Price

Materials: Cast bronze on bronze and stone base

Location: St. Paul campus lower quad

Standing, the near life-sized cast bronze statue of Archbishop John Ireland looks over the lower quad. The base is stone with a concrete core and bas-reliefs in bronze donated by Virginia Donahoe in honor of her father. The plaques include a dedication, an owl (education), a dove (the church) and a dove with a laurel wreath (community).

This monumental statue of the founder of the University of St. Thomas is situated so that most students, faculty and staff see it every day, reminding us all of our long heritage and the ideals of Archbishop Ireland.

Feel free to post in the comments section which pieces you agree with, which you think are missing and what your top 10 would be.